New York is so much more than Manhattan.

There are Second Acts in American lives.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Artists need not only skill but something to say.

Those are three important lessons one can learn from photographer William Meyers’s remarkable show, “Outer Boroughs,” on display now at the Schwarzman branch of the New York Public Library. Occupying much of the wall space on the third floor of the library’s Fifth Avenue flagship branch, the photo exhibit depicts the everyday life of Brooklyn, Queens, Staten Island, and the Bronx from 1990 through 2008. Its 90 images capture a rapidly changing city.

Many of Meyers’s pictures already feel as though they come from a different era—especially as they depict the speed with which many former slums have become fashionable enclaves. Pictures of previously dilapidated sections of Brooklyn’s Bushwick and the Bronx’s Mott Haven now seem almost quaint when set beside images of these gentrifying neighborhoods today. That sense of transformation is augmented by Meyers’s use of a 35-millimeter film camera with a Leica lens. All of his photos are silver gelatin prints on 11-by-14 inch paper, and all were developed by Chuck Kelton, an acknowledged master of the dark room. There are no digital images.

Black-and-white photography is typically characterized by high contrast and high drama. But Meyers’s work also offers moody introspection and an appreciation for quotidian moments—along with an art photographer’s interest in the delicate qualities of light and dark and the transient beauty of urban landscapes. Meyers told me that his aim was to take photos where ostensibly “nothing was happening” and to convey the significance and grace in what was before him. None of the photos are forced or staged.

The show’s inspiration, Meyers says, came from a visit he made to a B. Dalton bookstore on Fifth Avenue in 1990. Examining a heap of books of New York photographs, Meyers noted that all the pictures were of “the city”—i.e., Manhattan. The story of the other boroughs—where most of New York’s people live and where much of its industry lies—hadn’t been told. Meyers was also drawn to the city’s grand physical forms—its large cemeteries, parks, and beaches, and its subways and roadways.

One haunting image shows a colossal lot in Co-Op City, where many of Gotham’s school buses are parked at night. Devoid of human faces, the picture, Meyers says, is meant to convey the power of a bureaucracy to force children to go long distances to attend classes in the interest of arbitrary administrative aims. Meyers’s range is typified by his pictures of the Bronx: a Riverdale bluff above the Hudson in the handsome Charlotte Bronte apartment complex; enthusiastic crowds admiring mechanized Christmas displays in Pelham Gardens; aging warehouses in Castle Hill; people on the street outside the old Yankee Stadium, indifferent to the nearby sporting contest; the windows of a low-rent furniture store peddling items in heavy slip covers along Fordham Road.

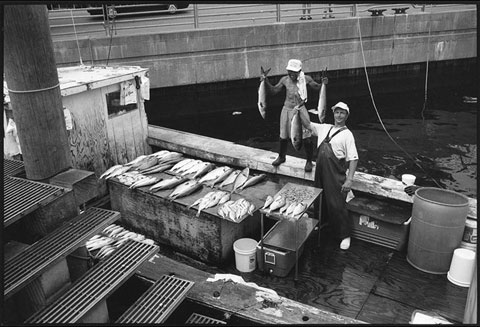

The contrasts between tableaux in Meyers’s work is reminiscent of Edward Hopper, often evoking the frequent emptiness of city life on the one hand while capturing the variety, energy, and warmth of city inhabitants on the other. An example of the first is a picture of Greenpoint on the night before a New York City Marathon. Plainly from an earlier time, the image shows a vacant and slightly menacing scene. In the second category, however, we see a baker on Arthur Avenue, a smiling little girl holding a scrunchie in Parkchester, and the fishermen of Sheepshead Bay, displaying their catch. The city’s ethnic diversity comes through in pictures of a Bukharin singer in Forest Hills, a Romanian restaurant in Sunnyside, a meeting of a Catholic youth organization in Sunnyside, a Greek restaurant in Astoria, and a Jewish Orthodox wedding in Flushing Meadows Park.

Even when Meyers picks familiar subjects, he avoids obvious takes on them. Thus, his picture of the start of the New York City Marathon does not focus on the mass of runners but instead zeroes in on one individual, and his photo of a famous Pepsi sign along the East River emphasizes not the structure but the people around it. While some of the photos reflect Meyers’s interest in formal questions in photography and his admiration for Modernists like Henri Cartier-Bresson and Eugène Atget, the greatest number are simply studies of the city’s people and places. The exhibit is accompanied by a book, light on text or description, save for an excellent introductory essay by journalist and urban historian Francis Morrone. Otherwise, the photographs simply identify the location where they were taken and the date.

A septuagenarian who came to photography following careers as a senatorial staffer and businessman, Meyers has been a contributor to City Journal and a frequent critic for The Wall Street Journal and, before that, The New York Sun. He notes that many exhibits of academically trained photographers are technically excellent but devoid of anything to say, as the exhibitors haven’t done much real living. That quality of real life is in abundance in his show.

(“Outer Boroughs” runs from March 27 to June 30 at the Stephen A. Schwarzman Branch of the New York Public Library, which is located from 40th to 42nd Street on Fifth Avenue.)