In 1982, I moved with my husband and our two young children into a partly renovated brownstone in Park Slope, Brooklyn. Last year, New York pronounced the area “the most livable neighborhood in New York City,” but in those days, real-estate agents euphemistically described it as “in transition,” meaning that the chances you’d get mugged during a given year were pretty good. Educated middle-class couples like us, who had been moving into the area between Seventh Avenue and Prospect Park for more than a decade, lived alongside the Irish, Italian, and Puerto Rican immigrants who had given Brooklyn its working-class identity and its former nickname, “Borough of Churches.” For us, Saint Francis Xavier’s was just the sponsor of our children’s Little League teams, but it remained a religious and community center for those who also frequented smoke-filled bars on Seventh like Snooky’s and Moody’s.

Among the old-timers was our neighbor Peggy Lehane. Her late husband had been a postal worker, and, like a lot of Park Slopers back in the day, she helped the family’s modest finances by taking in boarders in their four-story house. Legend had it that at one time she had a clientele of respectable bachelors and shabby “heiresses” to whom she served tea on silver trays. By the time we arrived, her boarders were elderly men and women on government assistance. We could hear the 3 AM moaning of these sad creatures and smell the contents of their bedpans, which they sometimes tossed into the patch of grass in back. Like the neighborhood, the house was transitional. More than once, and much to the wonderment of my children, ambulances arrived to remove a white-sheet-covered body.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

As the decade proceeded and crime worsened, Park Slope trembled between shabby respectability and drug-fueled violence. Rumors circulated of a crack house near Prospect Park, which had become a dangerous shadow of the original Olmsted-and-Vaux masterpiece. The streets around us endured a nightly explosion of shattered glass from car windows. Kids on their way home from elementary school were knocked down; parents walking from the subway station were held up at gunpoint. When my children went to camp, suburban kids, hearing that they were from Brooklyn, would ask: “Have you ever been shot?”

Our neighbor’s house reflected the Slope’s perilous condition. When we first moved in, Mrs. Lehane, always wearing a faded but neatly pressed dress, thick stockings, and lipstick, used to sweep the sidewalk with the intensity of a corporate lawyer on a gym treadmill. Now, her lipstick was smudged, her dresses were torn, and her stockings sagged. Instead of elderly renters, she took in “former” alcoholics and drug addicts living on disability payments. Mrs. Lehane’s children had moved to Long Island, but her foul-tempered granddaughter moved in, supposedly to oversee the house. The granddaughter’s violent fights with her boyfriend would sometimes wake us in the middle of the night. One day, Mrs. Lehane disappeared—to a nursing home, I heard. Many of our friends and acquaintances—fed up with vagrants on their stoops and graffiti, or terrified for the safety and education of their kids—left as well. I don’t know what combination of denial and passiveness made us stay. It seemed inevitable that something terrible would happen.

And so it did. One October night in 1995, after putting our Brooklyn-born youngest child to bed, my husband smelled smoke. Sure enough, a thin film of gray was swaying through our second-floor hallway, and we quickly spotted sickening black waves of the stuff pouring out of the moldings atop our bedroom windows. We ran outside to find the street jammed with fire trucks, ambulances, and awestruck neighbors. For the next two hours, we sat on a neighbor’s stoop and watched the Lehane house—its 1890s mahogany-trimmed parlor; its oak parquet floors; its memories of bourgeois Victorian respectability, of hard-knock immigrants, of addiction and decay—consumed in a conflagration apparently caused by a tenant who’d fallen asleep with a lit cigarette in his hand. We were lucky: our house suffered only some smoke damage. Others were not: several firemen were hurt, and a boarder died from smoke inhalation. For the next three years, the charred and empty house brooded over the block, a symbol of an uncertain urban future.

If you’ve been in Park Slope recently, you can probably guess how things turned out for the Lehane house. But you may not know why. How did the Brooklyn of the Lehanes and crack houses turn into what it is today—home to celebrities like Maggie Gyllenhaal and Adrian Grenier, to Michelin-starred chefs, and to more writers per square foot than any place outside Yaddo? How did the borough become a destination for tour buses showing off some of the most desirable real estate in the city, even the country? How did the mean streets once paced by Irish and Italian dockworkers, and later scarred by muggings and shootings, become just about the coolest place on earth? The answer involves economic, class, and cultural changes that have transformed urban life all over America during the last few decades. It’s a story that contains plenty of gumption, innovation, and aspiration, but also a disturbing coda. Brooklyn now boasts a splendid population of postindustrial and creative-class winners—but in the far reaches of the borough, where nary a hipster can be found, it is also home to the economy’s many losers.

To understand the emergence of the new Brooklyn, it’s best to start by recalling its original heyday. From the mid-nineteenth century to 1898, when it became part of New York City, Brooklyn was one of the nation’s preeminent industrial cities, and its dominance continued until about 1960. Facing New York’s deepwater harbor and the well-traveled East River, Brooklyn’s waterfront was lined with factories. Workers in those factories lived in the borough’s numerous tenements, row houses, and subdivided townhouses. Some worked the assembly line in the Ansonia Clock Factory in Park Slope. (It later became the neighborhood’s first condo-loft space.) Others worked in the Brooklyn Navy Yard, in an area now known as Vinegar Hill. Still others worked on the docks in Red Hook, the inspiration for the Marlon Brando movie On the Waterfront; in the Arbuckle coffee-roasting factory under the Manhattan Bridge; in the paint factories and metal shops in Gowanus; in the breweries in the once-German enclaves of Williamsburg, Greenpoint, and Bushwick; and in the pharmaceutical factory founded in East Williamsburg by Charles Pfizer. They worked in the Domino sugar refinery, at one time the largest in the world, whose big red DOMINO sign (still illuminating the East River at night) was all that some Manhattanites knew firsthand of Brooklyn.

But by the late fifties, a new kind of person was interested in sharing the borough with the factory laborers and dockworkers and the butchers and deli owners who served them: an educated person with a little more money and a lot more “culture.” Despite its blue-collar reputation, Brooklyn had always had a moneyed class: doctors and lawyers on the “Gold Coast” of Prospect Park and business owners in mansions near their factories in Williamsburg and Bushwick. The more modestly moneyed newcomers were a different breed: writers, artists, small antiques dealers, and designers priced out of Greenwich Village but unwilling to move too far from their crowd. Truman Capote and Norman Mailer were the most notable of those who migrated across the Brooklyn Bridge into the federal- and Victorian-style houses of Brooklyn Heights. Soon, in a now-familiar pattern also seen in Manhattan neighborhoods like Soho and Tribeca, upwardly mobile professionals joined the artistic pioneers.

“Professionals”: that’s the way the gentrifiers were usually described. But who were they? According to Suleiman Osman’s recent history, The Invention of Brownstone Brooklyn, they were—and still are—comrades of the “white-collar revolution,” employees of a post-industrializing America. After World War II, improvements in transportation and communications enabled companies to centralize management even as they spread production across the nation. Manhattan was the logical place to become what Osman calls the “command and control center” for these enterprises; after all, it was already the nation’s art, media, philanthropy, and publishing hub. New York–based companies started head-hunting for accountants, bankers, lawyers, and managers, as well as advertisers, publicity agents, and writers. The workers who filled these positions, in turn, expanded the customer base for New York’s cultural and philanthropic organizations, which began hiring as well. Federal, state, and city government were also creating agencies that helped swell the white-collar workforce. By 1960, white-collar workers outnumbered blue-collar workers nationally. And Manhattan—the Rome of white-collardom, the Mecca of strivers from the staid heartland and the slow-moving South—was teeming with middle- to upper-middle-class workers.

This new workforce needed somewhere to live. A surprising number turned up their noses at New Rochelle and West Orange. Perhaps their college social-sciences courses had taught them to write off the suburbs as “alienating.” Perhaps the influence of Kennedy-era European sophistication led them to scorn the purportedly tacky conformity of the bridge-and-tunnel crowd and to grimace at the sterile white-brick apartment buildings rising in Manhattan to house their kind. Unlike their immigrant parents, who associated city life with poverty, teeming tenements, and foul streets, they saw in the old urban areas the “authenticity” and “community” that the suburbs and the high-rise city lacked. They looked across the Brooklyn Bridge and found walkable, human-scale, leafy, and historic streets with houses displaying the craftsmanship of a seemingly more gracious age. (In reality, the elaborate woodwork in my neighborhood, at any rate, was prefabbed by Victorian developers.)

As their numbers increased, the professionals crossed Brooklyn Heights and trekked deeper into the blue-collar borough. Osman refers to the settlers as “romantic urbanists”; they—or should I say “we”?—were looking for an organic connection to history and an echo of rural life. With the help of a surging real-estate industry, we gave our new enclaves bucolic names—Heights, Hills, Gardens—and settled in happily, though uneasily, next to our less privileged neighbors.

The unease was understandable—and mutual. Though our presence meant responsible, even meticulous, homeownership, it also meant rising rents. The major gripe against gentrifiers has always been that they price out the natives. This trope presupposes an economic stability rare in a dynamic place like Brooklyn—the “natives” were just the most recent of many placeholders—but there’s some truth to it. Adding to the tension, the gentrifiers represented an unfamiliar cultural type, with their own aesthetic stance and resonant mythology. They sentimentalized working-class neighborhoods, but they had little in common with the Lehanes and their ilk. The newcomers tore down the aluminum awnings and ripped up the linoleum floors as fast as they could. Nor did the new urban middle class understand the domestic roughness, the mobsters, and the turf-protecting gangs that were also part of the authentic Brooklyn community.

The mutual unease was understandable most of all because the white-collar enthusiasm for the area accompanied Brooklyn’s manufacturing decline. By the 1970s, the borough was hemorrhaging both jobs and ethnic Brooklynites. Most of the factories under the Manhattan Bridge had already left by the 1950s. Williamsburg’s famous Eberhard pencil factory, employing locals since 1872, moved to Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, in 1956. In the 1960s, the new technology of containerization led the shipping industry to abandon Red Hook for the more spacious New Jersey docks. The two remaining anchor tenants at the Brooklyn Navy Yard—Seatrain and Coastal—closed in the 1980s. Between 1950 and 1980, Brooklyn lost half a million residents. And the blue-collar decline continues in the new millennium, with the borough losing more than 9,000 manufacturing jobs between 2005 and 2010.

Policymakers treated a changing Brooklyn with a tin ear and a heavy hand. One of the sorriest examples of their handiwork was Red Hook. Well before shipping began to leave the docks in the late 1950s, Robert Moses had severed Red Hook from the rest of South Brooklyn by building the Gowanus extension of the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway, one of the most despised of his many projects. At its best, Red Hook had been tough and gritty; its Moses-induced isolation just about guaranteed that it would get worse.

A new generation of policy officials following Moses did only marginally better in planning Red Hook’s future. Reacting to Moses-era excesses and prone to the same spirit of blue-collar sentimentalism that the gentrifiers felt, they tried to ward off manufacturing’s flight through radical zoning restrictions. In a 1961 regulation, the city reserved Red Hook’s waterfront—along with nearly the entire Brooklyn coastline—for industry. Even though the area had once had commercial and residential buildings nearby, its magnificent views of the harbor and the Statue of Liberty were now preserved in industrial-strength amber. The waterfront began a decades-long and largely fruitless wait for manufacturing’s return.

Lax crime-fighting and overgenerous social programs accelerated Brooklyn’s decline. By the 1960s, tens of thousands of blacks and Hispanics migrating from the South and Puerto Rico had arrived in the borough, almost all of them uneducated and unskilled and hence unprepared for an economy bleeding low-skill jobs. No-questions-asked welfare policies and the easy availability of heroin led many of these new arrivals to become dependent on government, dangerous, or both.

A large number of Brooklyn’s black and Puerto Rican residents lived in the 100 public-housing projects that dotted the borough. In the 1930s, the New York City Housing Authority had built its first large project in Brooklyn—in Red Hook, in fact, to house dockworkers’ families. The authority added another large project nearby in the 1950s, and many more followed elsewhere. A decade later, the dockworkers left the buildings, which then became home to the nonworking, welfare-dependent, and increasingly dysfunctional poor. By the time I moved to Park Slope, in the early 1980s, Red Hook was one of the city’s scariest neighborhoods. Not that it was all that different in that regard from Bushwick, Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brownsville, or Crown Heights. The criminals, now often hopped up on crack, spilled over into working-class neighborhoods and then into wealthier gentrifying areas. Some aging addicts and ne’er-do-wells took up residence in single-room-occupancy buildings. As the 1990s dawned, the gentrifying middle class started to follow white ethnics like Mrs. Lehane’s kids to the suburbs. Brooklyn came awfully close to becoming an East Coast Detroit.

But it didn’t, for three major reasons. First, policing reform brought a dramatic reduction in crime. When I moved to Brooklyn, Fifth Avenue, only three blocks from my house, was a bleak expanse of brazen drug dealing, liquor bodegas with cashiers sitting inside Plexiglas cages, and Salvation Army outposts. By the mid-1990s, the dealers and robbers and worse had been moved along, either to upstate prisons or to less antisocial activities. The avenue is now the very image of gentrification, overflowing with hip boutiques and restaurants, many owned by young entrepreneurs. About a mile away from me is Myrtle Avenue, a long stretch that people once called “Murder Avenue.” These days, the street is safe enough to attract young businesses, much as Fifth Avenue did a decade ago. The same goes for parts of Red Hook, Bushwick, Gowanus, and beyond. Only 15 years ago, Bed-Stuy was about as inviting to white-collar home buyers as Islamabad. After the 81st Precinct, which encompasses the eastern half of the neighborhood, saw a 64 percent plunge in violent crime between 1993 and 2003, the lawyers, editors, artists, and nonprofit administrators started venturing in.

Brooklyn also benefited from the Giuliani and Bloomberg administrations’ rezoning of fallow industrial neighborhoods for “mixed” uses, so that residential, commercial, and light-industry buildings could occupy the same area. These decisions have met with fierce resistance, with Brooklyn’s gentrifiers—ironically, given their historical role in changing the borough—among the most vociferous in arguing that grabby real-estate interests and their friends in government are driving out an indigenous population. Bruce Ratner’s much-reviled Atlantic Yards project, which took advantage of the government’s bullying eminent-domain powers, lends some credence to the charge. But mostly, Brooklyn’s transformation has come from the ground up. In the beginning, as Osman observes, gentrification spread because “a few families decided to cross” Atlantic Avenue, the southern boundary of Brooklyn Heights. The rezoning that finally took place decades later was simply bowing to reality: large factories were gone for good, and young singles and families wanted in.

The third reason for Brooklyn’s modern revival was the arrival of a new generation of gentrifiers, a large group of college-educated folks who, like the previous generation, found the urban, neighborly, and safer streets of the borough mightily attractive. The number of college-educated residents in Williamsburg increased by 80 percent between 2000 and 2008. Today, 30 percent of the residents of Park Slope, Cobble Hill, and Boerum Hill have master’s degrees or higher.

Unlike their predecessors, however, these grads are not only artsy; they’re tech-savvy and entrepreneurial. Don’t confuse them with the earlier artists and bohemians who daringly smoked pot at Brooklyn Heights parties. These are beneficiaries of a technology-fueled design economy, people who have been able to harness their creativity to digital media. In a 2005 report, the Center for an Urban Future estimated that 22,000 “creative freelancers”—writers, artists, architects, producers, and interior, industrial, and graphic designers—lived in Brooklyn, an increase of more than 33 percent since 2000. The Brooklyn Economic Development Corporation has dubbed the area from Red Hook to Greenpoint the “Creative Crescent.”

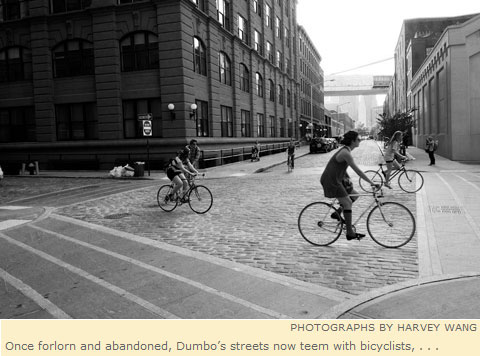

The new gentrifiers have also, surprisingly, re-created Brooklyn’s identity as an industrial center, locating commercial kitchens, artists’ lofts, and crafts studios in retrofitted factories in Sunset Park, Gowanus, and downtown Brooklyn. If they have to commute to work, they want to ride their bicycles, which is easier to do if you don’t have to cross the East River. (Brooklyn may be one of the only places in the world that occasionally offers valet bike parking.) Many have started their own boutique firms. In its report, the Center for an Urban Future also noted that “freelance businesses have been a faster growing part of the Brooklyn economy than employer-based businesses.” The number of Brooklyn-based firms spiked from 257 in 2001 to 433 in 2009.

The two areas of Brooklyn that best capture this past decade’s creative-class gentrification are Dumbo and Williamsburg. Dumbo’s story is as quirky as its winding streets. In the 1970s and ’80s, Dumbo—the letters stand for “Down Under the Manhattan Bridge Overpass”—was one of the most forlorn industrial sections of Brooklyn. Few people had lived in Dumbo during Brooklyn’s industrial heyday, but many had worked there. Once the businesses left, all that remained were derelict buildings.

In 1981, though, developer David Walentas took a look at the brick warehouses and factories (most dating from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries) and, taking a cue from his recent development successes in another former industrial area, Soho, bought 11 of them—almost an entire neighborhood. Or what he hoped might someday become a neighborhood: like Red Hook, Dumbo was still zoned solely for manufacturing, despite manufacturers’ indifference to the area. Walentas had to wait 17 years for the city to pronounce Dumbo “mixed-use” and for the area to come alive.

Walentas’s prescience—and patience—put him in an unusual position. Like many successful developers, he was able to make a lot of money: space in the buildings he bought for $6 per square foot now sometimes sells for $1,000 per square foot. But unlike other developers, Walentas owned so much of a neighborhood that he could play God. Also, since he was making so much money from the properties overall, he could give rent breaks to commercial tenants that he viewed as desirable—for instance, upscale retailers like West Elm, the modern-furniture outlet, and Jacques Torres, a high-end chocolatier—while refusing chains like Duane Reade, which, he felt, set the wrong, down-market tone.

Helping Walentas was the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission’s 2007 decision to make Dumbo a historic district, including not just the buildings but also the defunct train tracks and Belgian-block streets and sidewalks. Now, no other developers could ruin the gritty-charming streetscapes or the neighborhood’s spectacular views. Adding to Dumbo’s appeal is the newly opened, long-in-the-making, and still-evolving Brooklyn Bridge Park, where tourists can arrive by ferry from Manhattan and Governors Island. Dumbo, whose success has continued unabated through the Great Recession, is today one of the wealthiest and fastest-growing neighborhoods in Brooklyn. Using neighborhood boundaries rather than zip codes, Property Shark deemed it the fourth-priciest residential area in New York City, ahead even of the Upper East and West Sides.

For all its appeal, Dumbo would never have become such a glamorous destination without the influx of twentysomething digerati to buy its condos and work in its lofts. These settlers needed modestly priced, cool environments in which to start their businesses, and in the late nineties, Dumbo was both those things. Dumbo is now home to many start-ups, particularly digital-media marketing and communications firms with whimsical or artisanal names like Carrot Creative, Huge, Brooklyn Digital Foundry, Big Spaceship, and SawHorse Media. Etsy, the hugely popular online marketplace of handmade goods—the firm was recently valued at $300 million—has its home there. Boutique businesses and freelancers abound as well. Workshop, a firm headed by three graphic designers, creates the printed material for the TED Conferences and the New York Philharmonic. It shares office space, ideas, lunch, and a more-than-occasional beer with an informal collective of writers, web designers, illustrators, and social-media consultants who call themselves Studiomates.

Walentas’s company, Two Trees Management, has given a discount rental rate to the Polytechnic Institute of New York University to run a tech start-up incubator, which advises would-be entrepreneurs about raising capital, finding work space, and the like. Brooklyn Law School has also set up a clinic to advise wannabe entrepreneurs on the legal end. Walentas isn’t the only one enjoying the irony that a former site of industrial toxins and drudgery is now the city’s 90th protected historic district, boasting an educated workforce and some of the most expensive real estate in the country.

Farther up the East River lies Williamsburg, an even less probable site for gentrification. Williamsburg’s working-class homes and tenements weren’t likely to attract a striving middle class, and in the 1970s, persistent suspicious fires had made it even more undesirable. Williamsburg did, however, have the advantage of being one easy subway stop from Manhattan’s increasingly expensive East Village. By the 1990s, Manhattan hipsters had begun settling alongside Williamsburg’s white ethnics. But it wasn’t until 2005, after 30 years of indecision, that city officials finally rezoned Williamsburg for more residential development. Now, for better or worse—in the end, mostly for better—Williamsburg is Condo City. At the waterfront site of a former garbage-handling facility soars Edge, two glass towers with gyms, an indoor pool, outdoor terraces, a yoga studio, and screening rooms. The Real Deal, a real-estate magazine, reports that Edge sold more units than any residential building in the city in the first half of 2011. The area is attracting an increasing number of Wall Streeters and even B-list glitterati.

Traders and glass penthouses aside, the true symbol of the neighborhood’s emerging identity is a new demographic: the hippie entrepreneur, who specializes in two consumer industries—music and food. Back in the 1990s, local bands played in abandoned factories and warehouses; these dubiously legal locations gave the groups an illicit air. Today, a lot of them—Yeasayer, Grizzly Bear, Dirty Projectors, and Vampire Weekend, to name a few—are composing music for major movies, appearing on Conan O’Brien’s late-night show, and performing in completely aboveboard bars and clubs for throngs of metropolitan hipsters and European tourists.

Williamsburg’s culinary hippies, meanwhile, have a commitment to organic ingredients that borders on the spiritual. Some even work as “urban farmers” on local rooftops. They sell their products to farmers’ markets, to the borough’s many “locavore” restaurants, and to small food manufacturers in Williamsburg and other Brooklyn neighborhoods. The new wave specializes in combining the homespun with the exotic: cucumber soda, or doughnuts in flavors like hibiscus and dulce de leche. Some of the hippie entrepreneurs are dropouts from the Manhattan establishment; Daniel Sklaar, for example, left his finance job to open Fine and Raw, a company that produces raw chocolate with what its website calls “conscious ingredients.”

Steve Hindy and Tom Potter, founders of Brooklyn Brewery, epitomize the peculiar combination of hipster localism and business savvy characteristic of the young Brooklyn firms. Both had been company men—Hindy an Associated Press correspondent and Potter a Chemical Bank lending officer—before opening their Brooklyn plant in 1996. They were clever enough to see the marketing possibilities in Brooklyn’s changing identity and to ignore advice from establishment grown-ups to find a different name for their beer. Instead, they hired legendary designer Milton Glaser to create a seventies-style, retro-cool Brooklyn Brewery logo. Today, the brewery sells its products all over the world and is among the top 30 beer producers in the nation.

The problem is that these boutique businesses have a limited impact on the borough’s total economy. For all their energy and creativity, Brooklyn’s young entrepreneurs tend to have few employees, and they’re not likely to be hiring large numbers in the future. The factories of the past employed hundreds, if not thousands; Dumbo alone once had three firms that each employed more than 1,000. Today, Etsy, one of the area’s more successful companies, has a staff of just 180. The old Brooklyn Navy Yard now rents space to 275 businesses, employing 5,800 people. That’s an impressive rise from 3,600 in 2001, true. But compare it with the Yard at its World War II peak, when it had 71,000 workers, or in 1959, when it employed “only” 15,000. Even Brooklyn Brewery has only about 50 employees, small potatoes when you consider that Schaefer Beer’s Brooklyn factory—now a luxury building called Schaefer Landing—once had 1,000.

There are numerous reasons for the disappointing employment stats. For one thing, Brooklyn’s young companies often appeal only to niche markets, usually people like their owners. For another, they benefit from the technology-improved productivity of manufacturing throughout the United States; it takes fewer workers to produce beer or chocolate than it did in the past. And if the firms do grow and hire a lot more workers, chances are that they’ll relocate. It’s extremely expensive and endlessly aggravating to transport raw materials into, and finished products out of, a borough strangled by the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway. Young businessfolks also face the familiar hurdles of all New York City firms: high taxes and burdensome regulations. It’s enough to bum out even the most idealistic hippie-entrepreneur.

Brooklyn’s story, then, doesn’t lend itself to a simple happy ending. Instead, the borough is a microcosm of the nation’s “hourglass economy.” At the top, the college-educated are doing interesting, motivating work during the day and bicycling home to enjoy gourmet beer and grass-fed beef after hours. At the bottom, matters are very different. Almost a quarter of Brooklyn’s 2.5 million residents live below the poverty line—in the housing projects of East New York, in the tenements of Brownsville, or in “transitional” parts of Bushwick and Bed-Stuy, all places where single-mother poverty has become an intergenerational way of life. Between 2000 and 2010, the percentage of the area’s population on welfare did decline markedly, but the number of Medicaid recipients almost tripled, to nearly 750,000. About 40 percent of Brooklyn’s total population receives some kind of public assistance today, up from 23 percent a decade ago.

To make matters worse, according to Crain’s New York Business, Brooklyn’s unemployment rate doubled between 2008 and 2009, a considerably higher rise than in Manhattan, Queens, or Staten Island. When manufacturing jobs do become available, they tend to require skills that high school graduates—and dropouts—lack. East New York and Brownsville also remain the highest-crime areas in New York.

And no one believes that’s transitional.

Research for this article was supported by the Brunie Fund for New York Journalism.