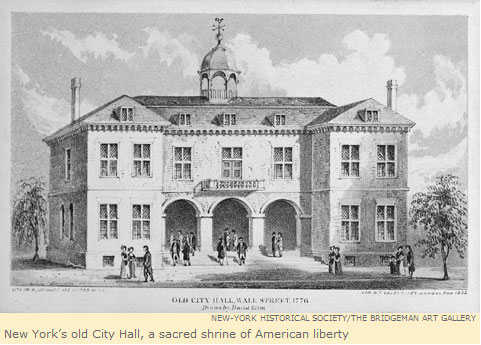

The corner of Wall and Nassau Streets where Federal Hall now stands—opposite the New York Stock Exchange and J. P. Morgan’s old office—is sacred ground for American liberty. In the cupola-crowned City Hall built there in 1699, representatives of the American colonies called themselves together for the first time, in the Stamp Act Congress of 1765, and declared their “undoubted right” not to be taxed but “with their own consent.” In May 1789, four days after George Washington’s inauguration on the balcony of the refurbished building, just renamed Federal Hall and housing the new Senate and House of Representatives, congressman James Madison opened debate on a proposed Bill of Rights, which he guided to the necessary two-thirds majorities in both chambers by the end of that summer. In that same building over half a century earlier, by a sweet coincidence, the free speech, free press, and trial by jury that the Bill of Rights protects had won their first great vindication in British America, in the famous 1735 seditious-libel case of printer John Peter Zenger. Its dramatic outcome put British authorities sharply on notice that Americans believed that they had certain God-given rights and would not give them up without a fight.

The trial had its origins in a spat over money that quickly escalated into a battle over fundamental rights and legitimate authority. When a new royal governor, William Cosby, arrived in New York in 1732, he demanded that the senior provincial council member, Rip Van Dam, give him half the salary that Van Dam had received as acting governor before Cosby reached the New World. Fair enough, according to custom; but Van Dam countered that he’d relinquish the £1,000 or so at issue only if Cosby gave him half the £6,400 worth of perks that the governor had already raked in even before starting his new job.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Cosby, ill-educated, ill-tempered, and implacable, decided to sue—but in which court? Since his greedy imperiousness had begun offending New Yorkers the moment he landed, he knew he daren’t trust an ordinary jury, and he couldn’t turn to the nonjury Chancery Court, of which he was the ex-officio judge, since even he didn’t have the brass to hear his own case. His solution: to ask the colony’s Supreme Court, whose judges were gubernatorial appointees, to sit as an equity Exchequer Court, an unusual but not unheard-of ploy that further inflamed New Yorkers, who reasonably thought that trials without juries violated their rights as freeborn British subjects.

Lewis Morris, chief justice since 1715 and owner of the vast Morrisania manor in Westchester, didn’t like the tactic, either, and vigorously agreed in April 1733 with Van Dam’s capable lawyers, James Alexander and William Smith, who objected that the proposed hocus-pocus of transmuting the Supreme Court into a juryless equity court was improper and illegal. Morris rebuked his two fellow justices for taking the opposite view, and published his rebuke. Cosby responded by summarily firing him in August and elevating loyal supporter James De Lancey to the chief justiceship instead. By so doing, he created in Morris, Alexander, and Smith powerful, canny enemies who could now attack him on the constitutional grounds that he had tried to take away a citizen’s property without the due process of a jury trial, and that he had arbitrarily dismissed a judge for trying to protect basic rights.

Attack him they did, with guns blazing. On the political front, Morris and his son began campaigning only weeks after the chief justice’s firing as anti-Cosby candidates for seats in the provincial assembly, which they won in the November 1733 election, and they began recruiting anti-administration candidates for the next autumn’s New York City Common Council elections. More important, on November 5, 1733, James Alexander and other Morris allies launched America’s first opposition newspaper, the New-York Weekly Journal, which Alexander edited and largely wrote. Most articles appeared under pseudonyms, though; the only name on the masthead was John Peter Zenger, the paper’s 36-year-old printer, who had arrived in America among the 2,000 to 3,000 Germans fleeing from famine in the Palatinate in 1710—the biggest German immigration of colonial times and part of Queen Anne’s effort to people her New World empire. After an apprenticeship to the King’s Printer in New York, Zenger had set up on his own, turning out tracts, pamphlets, and textbooks in English and Dutch.

The Journal’s attacks could be scurrilous, especially in its mock classified ads. One, searching for a runaway monkey given to “grimace and chattering,” broadly caricatured Cosby. Another, seeking a lost spaniel that fetched and carried fulsome “Panagericks” (on Cosby) to the establishment newspaper, lampooned gubernatorial toady and political appointee Francis Harison.

But most often, Alexander anchored his critique in a carefully explained political theory of British constitutionalism, much of which he learned, as did so many American colonists, from Cato’s Letters, written a decade earlier by the hugely influential radical English Whig journalists John Trenchard and Thomas Gordon. Alexander, who regularly reprinted Trenchard and Gordon in the New-York Weekly Journal, didn’t follow their Lockean radicalism all the way—not explicitly, anyway. He never went so far as to say, as Cato No. 11 succinctly declared, that “the sole end of men’s entering into political societies, was mutual protection and defence; and whatever power does not contribute to these purposes, is not government, but usurpation.” But he wholeheartedly endorsed Cato’s theory of limited monarchy, where the laws protect everyone’s basic rights against all state authorities, from the king on down.

Central to this scheme is a free press, as Alexander explains in the second and third issues of the Journal, which purport to be a letter from Cato himself. Nothing restrains a “powerful and wicked” minister so effectively as a free press, Alexander argues. It can “awaken his conscience, . . . sting him with the dread of punishment, cover him with shame, and render his actions odious.” Indeed, he asserts, “This advantage . . . of exposing the exorbitant crimes of wicked ministers under a limited monarchy makes the liberty of the press not only consistent with, but a necessary part of, the constitution itself.” So crucial is this right, concludes Alexander, paraphrasing Trenchard and Gordon, that “no nation ancient or modern ever lost the liberty of freely speaking, writing, or publishing their sentiments but forthwith lost their liberty in general and became slaves.”

Thus cloaked in the British constitution, Alexander, a Scottish-born former attorney general of New Jersey, set to flaying Cosby with patriotic fervor. Was it “prudent in an English governor to suffer a Frenchman to view our fortifications, sound our harbors, etc.?” asked the Journal after Cosby permitted a French warship to do just that. “Could we not, by seizing their papers and confining their persons, have prevented them in great measure from making use of the discoveries they made”—as Cosby failed to do? The same December 17, 1733, issue of the paper went on to remind readers that Cosby had arbitrarily displaced Chief Justice Morris and had added to the provincial council a newcomer to New York whose main distinction is “having first been and still he is, one of His Excellency’s counsel in his suit . . . against the Honorable Rip Van Dam. Esq.”

Surely, Cosby thought, he didn’t have to put up with this. Accordingly, at the start of the new year, the governor’s newly installed Chief Justice De Lancey, aged 30, asked the grand jury to indict whoever was responsible for all the seditious libels recently circulating in the province. The 19 jurors demurred.

Enflamed and emboldened, Alexander excoriated with redoubled zeal. “THE PEOPLE of this city . . . think, as matters now stand, that their LIBERTIES and PROPERTIES are precarious, and that SLAVERY is like to be entailed on them and their posterity, if some past things be not amended,” he thundered in the January 28, 1734, issue. After all, “the liberty of the press is now struck at, which is the safeguard of all our other liberties.” And sure enough, he charged in the April 8 number, “I think the law itself is at an end: We see men’s deeds destroyed, judges arbitrarily displaced, new courts erected without consent of the legislature, by which it seems to me trials by juries are taken away when a governor pleases.” What a list of malefactions!—the arbitrary firing of Chief Justice Morris (as well as the later firing of a local judge, Vincent Matthews) for upholding the law, the enchantment of the Supreme Court into a juryless Exchequer Court, and Cosby’s high-handedly permitting the Mohawk Indians to burn a deed by which they had transferred land to Albany settlers. With such goings-on, “Who is then in that province that call anything his own, or enjoy any liberty longer than those in the administration will condescend to let him do it?”

Less than a week before the Common Council elections, the Journal took one last swipe. Contrary to custom, it remarked, the governor made a practice of sitting in with the provincial council and meddling in its legislative function, as Van Dam had earlier complained to the Board of Trade in London. Such interference by a veto-wielding executive officer subverted the constitutional separation of powers, a concept well understood since antiquity, though still a decade away from getting its modern formulation by Montesquieu. Laws made in this way, the Journal opined, are “a nullity”—and “making a nullity of the constitution not only infers but introduces a nullity of liberty.”

The September 29, 1734, Common Council elections gave the Morrisite candidates a landslide. A week later, the Journal gloated by printing the list of victors and remarking that all but one “were put up by an interest opposite to the Governor’s,” while all the losers were Cosby supporters. Twisting the knife, Zenger printed a broadside with two celebratory ballads right after the election. A sample:

Come on brave boys, let us be brave

For liberty and law,

Boldly despise the haughty knave,

That would keep us in awe. . . .

Though pettifogging knaves deny

Us rights of Englishmen;

We’ll make the scoundrel rascal fly,

And ne’er return again.

Our judges they would chop and change

For those that serve their turn,

And will not surely think it strange

If they for this should mourn.

An outraged Cosby resolved to crush such effrontery. He asked a new grand jury for indictments over the “scandalous” songs, but though the jurors agreed that the ballads were libelous, they professed bewilderment as to who might have written or published them. Cosby then pressed the assembly and the provincial council to act. Though the assembly refused, the council voted on November 2 to order four issues of the Journal to be burned by the “common Hangman, or Whipper, by the pillory” and to direct the sheriff to arrest Zenger for publishing seditious libels “tending to raise factions and tumults among the people of this Province, inflaming their minds with contempt of His Majesty’s government, and greatly disturbing the peace thereof.” When New York’s mayor and aldermen wouldn’t let their hangman destroy the newspapers, the sheriff “delivered them unto the hands of his own Negro, and ordered him to put them into the fire, which he did,” James Alexander later reported.

With Zenger hauled off to jail—it was in the garret of City Hall—on November 17, 1734, Alexander and Smith volunteered as his lawyers and went to bail him out. Elementary fairness, they soon learned, was not in the cards for the printer. As Alexander explains in his Brief Narrative of the case, published in 1736 (and splendidly annotated by Stanley Nider Katz for Harvard University Press), English law requires bail to be set within the accused’s means. But for Zenger, whose net worth didn’t reach £40, Chief Justice De Lancey set bail at £400, so the printer languished in his attic cell, plagued by its leaky roof and drafty window, for the next eight months. To compound the unfairness, when a grand jury yet again failed to indict Zenger in January 1735, Attorney General Richard Bradley filed an “information” against him, a way of bypassing a grand jury and charging someone without an indictment.

With so much legal hanky-panky, Alexander and Smith immediately called into question the basic legitimacy of the whole proceeding. They formally took “exception” to the commissions of De Lancey and his fellow judge, Frederick Philipse, which appointed them to serve “during pleasure” of the governor rather than “during good behavior,” as was customary in England. As any reader of Cato’s Letters would know, officials who serve “at pleasure” easily decline into tools and henchmen of the person who can fire them, if that superior is as arbitrary as Cosby showed himself in firing Morris, trampling judicial independence and further subverting the separation of powers. De Lancey understood Alexander and Smith’s cheeky implication perfectly. And, proving them right by silencing them, he summarily disbarred them for their presumption.

Lawyerless after this unheard-of move, Zenger asked the court to appoint counsel for him, and De Lancey named John Chambers, a competent Cosbyite who pled his new client not guilty and asked for a so-called struck jury. Hanky-panky marred even this normally fair jury-selection method, in which the court clerk randomly chooses 48 names of freeholders and allows both sides to reject a dozen each, with the jury picked by lot from the remaining 24. The 48 “random” names included many non-freeholders, however, including some Cosby political appointees, along with his baker, tailor, and shoemaker. The court clerk pooh-poohed Chambers’s protest, but even De Lancey couldn’t swallow this particular injustice and ordered fair play, resulting in a half-Morrisite jury.

When the trial began on August 4, 1735, Chambers argued that there can be no libel without a specific victim, and he challenged the attorney general to prove whom exactly the supposedly libelous Journal articles targeted. When he sat down, it wasn’t Attorney General Bradley who rose as expected, however.

It was America’s foremost lawyer, Andrew Hamilton, of Philadelphia. Wary of Chambers, James Alexander had enlisted his good friend and fellow Scottish immigrant to defend Zenger pro bono. At 59, Hamilton was a vivid, accomplished political infighter who—according to lawyer Smith’s historian son, William Smith, Jr.—“had art, eloquence, vivacity, and humor, was ambitious of fame, negligent of nothing to ensure success, and possessed a confidence which no terrors could awe.” Heightening the drama of his unexpected appearance, Hamilton opened by saying, “I’ll save Mr. Attorney the trouble of examining his witnesses” and “confess” that my client “both printed and published the two newspapers” for which he is being prosecuted.

Well, that ends it, replied Attorney General Bradley. “I think the jury must find a verdict for the King.” After all, the law states—as it did at that time—that a libel is a libel even if it is true. As Bradley explained, government, which protects our lives, religion, and property, is too essential to allow people to weaken or subvert it by publishing scandal, whether true or false, about the magistrates who administer it. That way lies anarchy, and the law has always forbidden it. And that is why “the Governor and the chief persons in the government . . . had directed this prosecution, to put a stop to this scandalous and wicked practice of defaming His Majesty’s government.”

Oho, said Hamilton, his voice tinged with irony and mock surprise; I had no idea, until the attorney general pointed it out, that the governor was the butt of Zenger’s supposedly libelous articles, and I had thought Bradley had brought this prosecution on his own initiative, obsequiously “to show his superiors the great concern he had lest they should be treated with any undue freedom.” But now that he tells us that “this prosecution was directed by the Governor and Council,” and now that I look around and see the huge audience in this courtroom, “I have reason to think . . . that the people believe they have a good deal more at stake, than I apprehended.”

Surely, Hamilton continued, even Bradley must think the truth or falsehood of Zenger’s articles is a critical question in this case, whatever the law says. After all, he charged the printer in his “information” with “publishing a certain false, malicious, seditious and scandalous libel. This word false must have some meaning, else how came it there? . . . The falsehood makes the scandal, and both make the libel,” he contended. “Mr. Attorney has now only to prove the words false in order to make us guilty.”

Hold on, interjected the chief justice, backing up Bradley’s quite correct reading of the law. “You cannot be admitted, Mr. Hamilton, to give the truth of a libel in evidence. A libel is not to be justified; for it is nevertheless a libel that it is true.”

Hamilton begged to differ—at considerable length.

“Mr. Hamilton, the Court have delivered their opinion, and we expect you will use us with good manners,” De Lancey concluded. “You are not to be permitted to argue against the opinion of the Court.”

Then, gentlemen of the jury, it is to you we must now appeal,” said Hamilton, turning toward them. “You are citizens of New York; you are really what the law supposes you to be, honest and lawful men. . . . In your justice lies our safety.”

Easy there, De Lancey interposed: the only question for the jury is whether Zenger published the papers. According to the law, they must leave it to the Court to decide if they are libelous.

“The jury may do so; but I do likewise know they may do otherwise,” Hamilton countered. “I know they have the right beyond all dispute to determine both the law and the fact, and where they do not doubt of the law, they ought to do so. This of leaving it to the judgment of the Court whether the words are libelous or not in effect renders juries useless”—as had already happened when Bradley charged Zenger despite three grand juries’ refusal to indict him. And here Hamilton effectively snatched the trial out of the hands of the judges and the prosecutor and transformed it from a question of law into a question of politics. The issue became, as a contemporary observer remarked, not what the law was, but what “ought to be law, and will always be law wherever justice prevails.”

Echoing the language and political philosophy of Cato’s Letters, Hamilton told the jurors that “all freemen . . . are entitled to complain when they are hurt; they have a right publicly to remonstrate the abuses of power in the strongest terms, to put their neighbors upon their guard against the craft or open violence of men in authority, and to assert with courage the sense they have of the blessings of liberty, . . . and their resolution at all hazards to preserve it as one of the greatest blessings heaven can bestow.” The only restraint the law can put “upon this natural right . . . can only extend to what is false.” Otherwise, “were this to be denied, then the next step may make them slaves; For what notions can be entertained of slavery beyond that of suffering the greatest injuries and oppressions without the liberty of complaining; or if they do, to be destroyed, body and estate, for so doing?”

As for the libel laws curtailing free speech, almost all the precedents that the attorney general cites come from the tyrannical reigns of the Stuarts. They are mostly Star Chamber cases, that nonjury court where “the most arbitrary and destructive judgments and opinions were given that ever an Englishman heard of.” There, prosecutions were “set on foot at the instance of the Crown or its ministers” and—to take a swipe at De Lancey as well as Cosby—“too much countenanced by the judges, who held their places at pleasure (a disagreeable tenure to any officer, but a dangerous one in the case of a judge).” In those Star Chamber days, “great men” accused people by an “information,” and “the people of England were cheated or awed into delivering up their ancient and sacred right of trials by grand and petit juries.”

No wonder the Glorious Revolution of 1688 did away with such a tyrannical court: “The people of England saw clearly the danger of trusting their liberties and properties to be tried, even by the greatest men in the kingdom, without the judgment of a jury of their equals. They had felt the terrible effects of leaving it to the judgment of these great men to say what was scandalous or seditious, false or ironical.” We should let the Star Chamber and its cases stay dead: “In the reign of an arbitrary prince, where judges held their seats at pleasure, their judgments have not always been such as to make precedents of, but to the contrary.”

Free speech and trial by a jury of one’s peers: the whole case really is about these two great guardians of liberty, Hamilton put it to his 12 jurors, focusing the spotlight of history squarely upon them and asking them to play their part in a momentous constitutional drama. “Power may justly be compared to a great river, while kept within its due bounds, is both beautiful and useful; but when it overflows its banks,” he told them, it “brings destruction and desolation wherever it comes.” It needs checks and balances to restrain its inevitable tendency to excess—checks like the dozen men before him. “Let us at least do our duty,” Hamilton urged them, and “use our utmost care to support liberty, the only bulwark against lawless power.”

Lawless power precipitated this affair. Just as in the worst days of the Stuart era, we are seeing “prosecutions upon informations set on foot by the government to deprive a people of the right of remonstrating (and complaining too) of the arbitrary attempts of men in power,” Hamilton charged. “Men who injure and oppress the people under their administration provoke them to cry out and complain; and then make that very complaint the foundation for new oppressions and prosecutions.”

But under the British constitution, a jury can stymie such lawless administrators by refusing to ratify their unjust schemes—despite what the presiding judge may say, as Hamilton had asserted at the start of his argument. “The question before the Court and you gentlemen of the jury is not of small nor private concern, it is not the cause of a poor printer, nor of New York alone,” Hamilton summed up. “It is the cause of liberty; and I make no doubt but your upright conduct this day will not only entitle you to the love and esteem of your fellow citizens; but every man who prefers freedom to a life of slavery will bless and honor you as men who have baffled the attempt of tyranny; and by an impartial and uncorrupt verdict, have laid a noble foundation for securing to ourselves and our posterity, and our neighbors that to which nature and the laws of our country have given us a right—the liberty—both of exposing and opposing arbitrary power . . . by speaking and writing truth.”

The jury, after “a small time” of deliberation, came back with a verdict of not guilty, sparking three cheers from the spectators. The next day, Zenger was a free man, and the mayor and aldermen of New York gave Hamilton the freedom of the city and a gold box, engraved “Won not by money but virtue,” for his “learned and generous defense of the rights of mankind, and the liberty of the press.”

This defiant act of jury nullification didn’t change the law, of course. Even after the Bill of Rights became part of the U.S. Constitution, the government brought libel cases under John Adams’s shameful 1798 Sedition Act, which, however, finally made truth a lawful defense in federal cases; and later still, Jeffersonian Republicans brought such actions under state law, until a brilliant argument by Alexander Hamilton (no relation to Andrew) in an 1804 New York Supreme Court appeal prompted the state the next year to redefine libel as a false, malicious, and defamatory statement, with other states following suit.

But after 1735, British officials knew that American juries were unlikely to convict in libel cases, so such prosecutions became rare once the newspapers and James Alexander’s widely read Brief Narrative spread the tale of the Zenger verdict all across the colonies. These reports helped mold the political culture of British America, and, of course, the verdict opened the floodgates on a torrent of political pamphleteering that heightened the colonists’ reverence for liberty, constitutional rights, freedom of speech and of the press, and trial by jury. So when in 1772, British authorities seemed ready to carry out their threats to try American customs evaders in nonjury admiralty courts, Virginians formed the first revolutionary committee of correspondence and set the colonists on a course from which they never turned back.

Photo: Tiago_Fernandez/iStock