The Golden Gate Bridge is one of the most majestic structures on Earth. Even more impressive, perhaps, is that the bridge was built swiftly and opened in 1937, on time and under budget. This makes it a perennial source of inspiration for engineers and infrastructure mavens alike—especially today, when building major projects seems like a relic of the past.

How was this feat accomplished? It was not, as many assume, thanks merely to a more permissive regulatory environment. The bridge’s creation offers two main lessons.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

The first is that putting in place the legal and political structures for public works takes time. Though the actual building of the bridge was rapid, the process leading up to it spanned decades.

The second lesson is that an independent and flexible management structure, as well as financing that ties management to results, are essential for successful infrastructure projects.

Modern advocates of “abundance” often take a Pollyannish view of older public works projects, romanticizing a mythical past where it was easy to build things. Yet big public works are contentious by nature; there was no golden age of easy infrastructure.

“Abundance” types are also too optimistic about insulating infrastructure from political machinations. The truth is that independence, while essential, also comes with serious downsides, potentially creating long-term problems and undermining democratic accountability. Believers in good infrastructure need to think about builders’ incentives, both during building and afterward, if that infrastructure is going to work for the public.

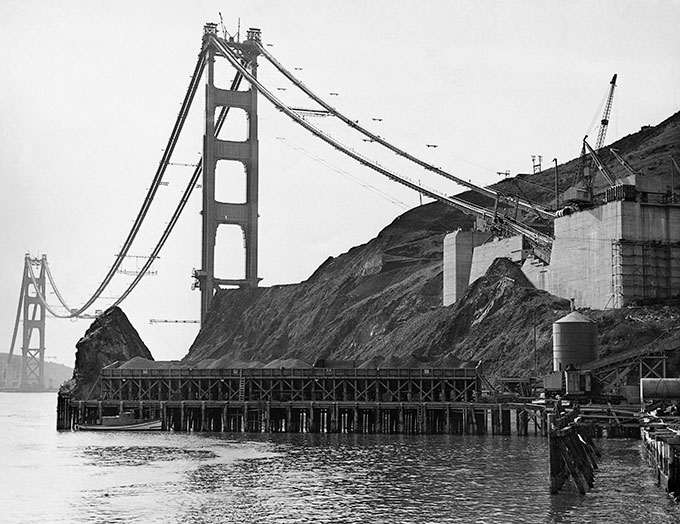

The Golden Gate Bridge is often held up as an example of public infrastructure built right. Many today note that the bridge took just four-and-a-half years to build—far less than the average time an environmental-impact review for a comparable project would take today.

But the whole process of building the bridge, from conception to completion, took much longer: 15 years from first public designs to completion. It took so long not because of engineering but because of politics. Before building the bridge, its designers had to create an independent governing “district” focused solely on this project—something then almost unprecedented in America.

The story begins in 1919, when the San Francisco Board of Supervisors asked noted engineer Michael O’Shaughnessy to figure out how to bridge the Golden Gate, the span of water that separated the city from Marin County to the north. O’Shaughnessy turned to Joseph Strauss, a less experienced but energetic fellow engineer.

Strauss spent years working on the bridge design. He solicited expert and public feedback and advertised the general idea of the bridge before he finally published the design at the end of 1922. It did not yet feature the famous full suspension across its two towers, instead relying in part on a cantilever that held up suspension wires.

While the designs were in, San Francisco needed to collaborate with Marin and other counties to fund and build the bridge. That meant a governance body that spanned several jurisdictions, and that in turn required a new state law. In 1923, the state legislature passed the Bridge and Highway District Act, allowing counties to form an independent or “special” district. The district could issue bonds, build a bridge and approach highways, and collect tolls to pay off the bonds.

The law was not wholly unprecedented, as special districts for infrastructure in America date to the late nineteenth century. But these districts had become common nationwide only in the previous decade. For example, 1923 also saw the formation of the East Bay Municipal Utility District, responsible for constructing a public water system and administering it in and around Oakland. Similarly, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey—originating as a way to unify the area’s ports—would soon take the lead on infrastructure projects like the George Washington Bridge and the Lincoln Tunnel.

Today, many believe that public infrastructure once required little public input and faced little legal opposition. Yet the bridge district was subject to both. Under the Bridge and Highway District Act, the bridge district had to win approval from voters in a referendum in each of the affected counties. That process took two years, including a delay so that San Francisco could secure another legal change to give it more votes on the district’s board.

The formation of the new district also prompted over 2,300 separate court complaints. These came mainly from taxpayers, who would find themselves on the hook if the tolls proved inadequate. These cases, though ultimately ruled meritless, took until the end of 1928 to resolve. The legislature then passed another law to try to protect the district from still more legal objections.

The district also needed approval from the War Department, which had to sign off whenever a bridge crossed navigable waters. Preliminary approval was provided in 1924 after six months of review. Then, the engineers changed the design to the soon-to-be-famous pure suspension bridge. That pushed final approval from the Department to 1930.

Next, in November 1930, voters in all six counties had to approve bonds to construct the bridge. The vote was contested: steamship lines, worried about navigation, tried to gin up opposition. Even O’Shaughnessy, who thought that the new suspension design would fail, opposed the bond issue. Ultimately, bridge supporters won handily, but not before a drawn-out political fight.

Finally, the district had to sell those bonds. Unsurprisingly, that yielded even more lawsuits, leading to another state law to protect the district. The lawsuits continued until June 1932.

When construction finally began early in 1933, the district had already accumulated $200,000 in debt, mostly from attorneys’ fees. Though originally intended to be funded entirely by bonds and tolls, the district had to impose property taxes to keep itself operating.

Today, we regard the Golden Gate Bridge’s construction as miraculously fast. But Joseph Strauss referred to it as “a thirteen years’ war . . . a long and torturous march.” He meant the onerous process of approval and funding—always contentious for innovative public works, then and now.

With approval and funding finally squared away, actual construction proceeded quickly. This was possible not only through a laxer regulatory environment but also because of the innovative design of the district’s governance, which put engineering ahead of bureaucratic constraint.

While the district had a formal board of directors and manager, the act that formed it provided that “the engineer [Strauss] shall have, under the direction of the general manager, full charge of the constructions and of the works of the district.” This independence gave Strauss and his team of engineers primacy over the management.

The district’s independence enabled it to attract some of the greatest engineering minds of modern history. Strauss, the chief engineer, was overseen by a special technical board of what the San Francisco Chronicle called “engineers of national and international reputation.” Those included Leon Moisseiff and Othmar Ammann, who had built some of the greatest bridges in history, and who pushed for the suspension design.

Also important was the nature of these engineers’ employment. The boundaries between in-government and out-of-government were more fluid in this period, with no fine distinction between salaried civil servants and contract workers. This enabled the district to recruit more easily, since it could craft an array of employment and contracting options.

The fluid employment structure extended to Strauss. Later histories characterize him as an engineer directly employed by the district. But Strauss’s term and pay were the result of what a judge later described as “an elaborate written contract.” Instead of working as a salaried civil servant, Strauss’s contract fixed his base compensation at 4 percent of the estimated $27 million cost of construction—over $1 million, out of which he had to pay for some of his own assistants.

Strauss refused to be a civil servant because he feared that a change in the district’s board could lead to his ouster. The board itself wanted him to be independent so that he could not resign without financial penalty. The resultant contract gave both sides the continuance in office necessary for success.

As chief engineer, Strauss had enormous discretion, and he exercised it. He awarded eight main contracts for the bridge’s construction and oversaw the day-to-day integration of the contracts, generally with success. He also helped install an innovative safety net under the bridge during construction. The net saved the lives of 19 men.

When the bridge opened on May 27, 1937, it was under-budget and early. Its tolls soon proved more than sufficient to pay down the bonds. And it was already apparent that the bridge would be a powerful symbol of the West Coast.

This success was driven by the fact that the bridge was to be funded entirely by tolls, and that its bonding power was limited. This gave Strauss and his team a strong incentive to stay under budget and on time. The district’s independence, in other words, was mediated by strict monetary constraints.

Yet the independence of the Golden Gate Bridge and Highway District created problems after the bridge was completed. As Louise Nelson Dyble explains in Paying the Toll: Local Power, Regional Politics, and the Golden Gate Bridge, the bridge’s success meant that it was generating more revenue than the district needed to pay off its bonds. Its independence also meant it faced little check on its spending habits.

Predictably, outlays soared. A report by the San Francisco Chamber of Commerce published not long after opening claimed that the bridge “operated on an extravagant scale” compared with the nearby Bay Bridge. An early 1950s state audit showed that operating expenses could be reduced by as much as 10 percent.

Despite this waste, by the 1960s, the Bridge District was projected to garner enough tolls to pay off all of its bonds by 1971. In the eyes of the district’s directors and employees, that was a problem—because after the bonds were paid off, the bridge was supposed to go toll-free. The district would then have no income.

To resolve this dilemma, the district’s directors absorbed loss-making ferry and bus companies. Paying for these required levying indefinite tolls on the bridge.

Today, the district is part of the larger Golden Gate Bridge, Highway and Transportation District. More than half a century after it was supposed to dissolve, it is still collecting tolls.

It has also fallen prey to the same bloat that afflicts many other public projects. In 2024, the district finished the first phase of constructing suicide-deterrent nets—an echo of Strauss’s safety nets. Unlike Strauss’s, though, these nets took six years to build, longer than the construction of the bridge itself. The nets cost over $300 million—more than a third of the bridge’s original real cost.

The story of the Golden Gate Bridge and Highway District demonstrates the promises and perils of public works. To be successful, such projects require independence and flexibility on the part of government managers. They also need concrete funding schemes that reward success. But the long-term effects of creating such independence can be deleterious in the extreme.

This dynamic can be seen in other infrastructure projects erected by public authorities, including, most famously, the many projects of New York’s Robert Moses. Moses’s good characteristics (his rapid construction of public works) and bad ones (his lust for unaccountable power) sprang from his control of special districts. Moses’s empire at the Triborough Bridge Authority gave him independence from political branches. Many focus their attention on Moses the man, but the structure that enabled and empowered him is just as important.

Institutions like Triborough or the Golden Gate District have their merits; they also have accountability problems that can’t be wished away. In their classic article ”When Governments Regulate Governments,” David Konisky and Manuel Teodoro argue that governments often have a harder time regulating other government agencies than they do regulating businesses or people. The Tennessee Valley Authority, for example, tended to violate the Clean Air Act and Safe Drinking Water Act far more often than private-sector groups did.

This counterintuitive result obtains because governments can’t identify residual claimants or clear malefactors to punish if the entire body refuses to cooperate. Instead, tax- or toll-payers end up footing the bill.

These days, the United States has 38,000 special districts—double the number of its municipalities. Another classic political-science article shows that layering these districts on top of municipalities leads to higher government spending. More independence and less accountability encourage “overfishing” of tax dollars from a common pool.

The Golden Gate Bridge was an obvious success at construction. Yet few then thought about the dangers of creating such an independent structure over the long term. Today’s supporters of public works need to ponder not only short-term flexibility but also how a project will meet the needs of citizens after it is completed. Political accountability can be stifling, but it’s necessary.

Public construction has always required the delicate balancing of efficiency with accountability. We cannot get around this tradeoff; it is a feature of how governments build things. What we can do is try to make sure that the incentives for public works managers are as aligned as possible with the public interest—both before and after construction.

Top Photo by Connor Radnovich/San Francisco Chronicle via Getty Images