Advocates of the misnamed “millionaire’s tax” enacted in New York State last year claimed that it would restore “fairness” to a tax code that favored the rich. After all, the statewide teachers’ union noted, “over the last 30 years, New York has cut its top personal income tax rate on the wealthy by one-half.” Technically, the union was right—but that was only part of the story. Thanks to the interplay of federal and state tax rules, Albany’s share of all income taxes paid by New York’s wealthiest residents has actually been rising since the 1970s. And it will soon rise to its highest level ever, if President Obama and congressional Democrats have their way. This is bad news for New York’s battered economy.

The last time New York was struggling with a major economic downturn, Washington gave the state and city a shot in the arm. In early 2003, Congress and President George W. Bush agreed to accelerate their already-scheduled temporary reductions in federal income-tax rates and to cut federal taxes on capital gains and dividends more deeply. Those investor-friendly federal cuts took effect at the same time as large temporary increases in both state and city income-tax rates, which the New York State Legislature had enacted over Governor George Pataki’s vetoes. The economic positives of the big Bush cut canceled out the negatives of the smaller state and city hikes.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Nearly seven years later, in the aftermath of a far more serious economic crisis, the winds of tax policy are blowing in a very different direction for New York. President Barack Obama won office on a promise to return the top two income brackets’ marginal rates (now 33 percent and 35 percent) to the levels in effect before his predecessor took office (36 percent and 39.6 percent). He’s virtually assured of achieving that goal no later than 2011, when the Bush tax law expires. With federal deficits swelling and pressure mounting for more “stimulus” spending, taxes could rise even as soon as this year. Meanwhile, the president’s allies in organized labor are sharpening another dagger for New York: a tax on financial transactions.

Under the circumstances, Albany couldn’t have picked a worse time to enact yet another temporary income-tax increase—yet that’s precisely what Governor David Paterson and the Legislature agreed to do last spring, as part of the 2009–10 state budget. This hike, twice as large as the one in 2003, has raised the top state rate to 8.97 percent on filers with taxable incomes of over $500,000 (and to 7.85 percent for those starting as low as $200,000).

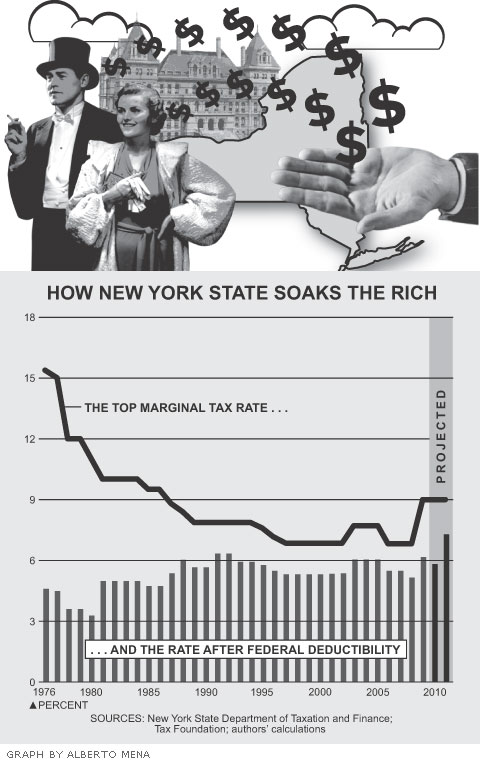

On the face of it, as the teachers’ union pointed out, New York State’s jacked-up marginal rate is still much lower than the all-time high of 15.35 percent reached in the mid-1970s. However, after allowing for federal deductibility, the effective state income-tax rate is actually higher now than it was 35 years ago. And current tax trends in Washington will push New York’s net income-tax cost—the difference between earning income here and in a no-tax state such as Florida or Texas—further beyond 1970s levels, even if the higher state rate expires on schedule in two years.

The explanation for these surprising facts lies in the complex way that the state tax code interacts with the federal one. Back in the 1970s, the federal income-tax structure was quite different. The top marginal rate—that is, the tax paid on every added dollar of income in the highest bracket—was 70 percent, which sounds unthinkably high even by Obama-era standards. Also, itemized deductions for all taxpayers—including deductions of state and local taxes—were unlimited, which effectively meant that those state and local taxes were discounted by 70 percent.

To understand how this worked, consider two hypothetical 1970s taxpayers. The first of them lives in New York and earns $300,000, putting him well into the top state and federal tax brackets. If he decides to work a little more and earn an extra $10,000, that money would be subject to a state income-tax rate of 15.35 percent and a federal rate of 70 percent. First he pays a painful $1,535 on this extra $10,000 to New York. But then the feds let him deduct that $1,535 from what he owes the IRS, leaving $8,465 subject to federal taxes. So his final bill on the $10,000 is $1,535 (the state income tax) plus 70 percent of $8,465, or $5,925—a total income tax of $7,460.

Now consider the second taxpayer, who has exactly the same extra $10,000 of income taxable in the top bracket but is lucky enough to live in a state with no income tax—Florida, say. That taxpayer pays nothing to Florida, and consequently must pay federal taxes on the entire $10,000. The bill comes to $7,000—a mere $460 less than the New York taxpayer’s, because the federal government hasn’t soaked up any of the Florida taxpayer’s cost. Another way of putting this: when New York’s top income-tax rate hit its 15.35 percent peak, the effective rate after federal deductibility—that is, the rate of taxation that the feds didn’t shield taxpayers from—was a much lower 4.61 percent. Though the total tax burden was staggeringly high in the 1970s, federal deductibility gave high-tax states like New York some shelter against competition from low- or no-tax states like Florida.

But that wouldn’t last. Over the next two decades, New York legislators reformed the state’s income-tax structure and reduced the top rate, which reached a 40-year low of 6.85 percent in 1997. Nevertheless, the effective top rate rose, a development that began with President Ronald Reagan’s slashing the top federal rate from 70 percent to 50 percent in 1981. This meant that the effective deductibility discount on state and local taxes was also reduced to 50 percent. Consider the same two taxpayers in 1981, when New York’s top-bracket rate stood at 10 percent: do the math, and you’ll find that the New Yorker paid $5,500 and the Floridian $5,000. That is, the Florida advantage grew.

Further changes were in store for high-income taxpayers with the federal tax reform of 1986, which reduced the top federal rate to 28 percent, significantly broadened the base of income subject to taxes, and disallowed deductions for state and local taxes for those subject to the Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT). And in 1990, President George H. W. Bush broke his “read my lips” promise and raised income-tax rates. Part of the tax hike was a new limit on itemized deductions (known as “Pease,” after the Ohio congressman who sponsored it). Pease included deductions of state and local taxes, and it had a greater effect than the AMT did on New York taxpayers in the high end of the top bracket, typically boosting their effective top state rate by almost a full percentage point.

You can see the effect of all these policy shifts in the chart on the previous page. Even as New York’s top marginal tax rate fell, its effective rate rose—and for high-income households, so did the share of income flowing to Albany and the relative cost of living in New York compared with a state with no income tax.

Unfortunately, it looks as though the trend is going to continue. The Bush tax cuts included a phaseout of Pease starting in 2006, its scheduled elimination in 2010, and its reappearance in 2011. Obama’s first budget would restore the full Pease limit and add yet another cap on itemized deductions. If Obama’s deduction cap winds up enacted and federal rates in top brackets increase in line with his plan, New York’s effective top tax rate will rise to at least 7.3 percent in 2011. That will be its highest level ever—more than half again as high as the effective top rate in the 1970s. The combined federal and state tax bite on salaries, wages, and bonuses of New York State residents in the top bracket will come to just over 48 percent.

For New York City residents, all these trends have been the same—except the starting points are higher. In the disco era, the combined state and city income-tax rate in Gotham reached a mind-blowing peak of 19.65 percent, equivalent to 5.9 percent after deductibility. By 2011, the city’s combined top rate of 12.62 percent (as it stood at the beginning of 2010) will cost the highest-income filers at least 9.9 percent, assuming adoption of Obama’s tax-policy aims—and assuming the city doesn’t use its deepening fiscal crisis as an excuse to increase its own income tax, “temporarily” or otherwise. In the city, the combined federal, state, and local tax bite on an added dollar of labor income in the top bracket will exceed 50 percent for the first time in 25 years.

Higher effective rates for state and city residents won’t be the only negative fallout in New York from imminent changes in federal tax policy. Because the state and city income taxes apply largely to the same taxable incomes that New Yorkers report on their federal returns, any federal shifts that shrink the taxable income base can likewise shrink state and city revenues.

Economists and tax-policy analysts have long recognized a link between taxpayer behavior and changes in marginal rates, especially in higher income brackets, where taxpayers have more control over the timing and nature of their incomes. When rates rise sharply, taxpayers respond by working and earning less, by shifting their “domicile” (or main residence for tax purposes) to lower-tax jurisdictions, and by using legal strategies to shift or shelter income in tax-exempt investments. Conversely, when marginal rates fall, upper-bracket taxpayers have less incentive to hide or shift income.

Based on a U.S. Treasury Department analysis of taxpayers’ responses to the Bush tax cuts, a 2006 report by the Manhattan Institute’s Empire Center for New York State Policy estimated that a return to the pre-2001 top federal tax rates would lead to annual revenue losses of $400 million for New York State and $72 million for Gotham. An econometric model developed for the Manhattan Institute by Boston’s Beacon Hill Institute predicted a slightly larger loss for the state but a smaller one for the city.

Revenues are already falling well short of projections. The state income-tax hike is raising about 10 percent less than the originally projected $4 billion, contributing to a yawning deficit. The imminent rise in federal taxes may temporarily reverse that trend, since Governor Paterson’s budget office expects a surge of capital gains in anticipation of federal rate hikes in 2011. But if the state’s experience with past swings in capital-gains taxes is any guide, that uptick will be followed by a slump the following year.

The specifics remain unsettled. But the trend in federal tax rates and rules is deeply unsettling for New York’s economic and fiscal outlook—and at the worst possible time.