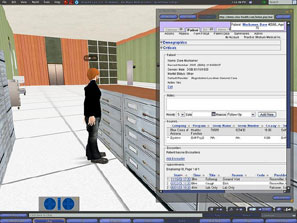

America’s first Ebola patient, Thomas Eric Duncan, first arrived at the emergency room of Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital on September 25 but was sent home by doctors. Three days later he was admitted to the hospital, where he subsequently died. The hospital claimed (and later retracted) that he was sent home because information about his travel history was not readily available in his electronic medical record (EMR). This is silly. There is no excuse for an ER physician’s failure to ask an African man with a fever and abdominal pain about his travel history when news stories about Ebola have been broadcast nightly for weeks. But the fact that the hospital thought to offer this explanation confirms what every American physician knows: hospitals and physicians are being required to buy EMRs that are expensive and difficult to use, and that often interfere with quality care rather than enhance it.

Proponents maintain that EMRs make health care more efficient and improve the quality of care by making patients’ records more accessible to the providers who treat them. Since 1991, the Institute of Medicine has been calling for the adoption of EMRs to improve the quality of care. An optimistic 2005 RAND study touted the benefits of EMRs.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Now the government is requiring them. The 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act stimulus bill set aside $19.2 billion to promote information-technology use. The majority of this funding goes to raising reimbursement rates for Medicare and Medicaid services delivered with “meaningful EMR use.” In 2013, 59 percent of hospitals and 48 percent of physicians had at least a basic EMR system. Providers who fail to demonstrate meaningful EMR use by 2015 will see their Medicare reimbursements reduced.

But implementation has been a costly fiasco. Hundreds of millions of dollars have been spent on poorly designed, time-consuming systems. Physicians and nurses struggle to use them and are actually seeing fewer patients. Patients complain that physicians are so busy entering data onto computers that they barely look up. Nurses spend hours entering information rather than verbally communicating important information to physicians and other nurses. EMRs also encourage providers to cut and paste extra information into their notes in the belief that more comprehensive notes are better (the billing for longer notes is also more remunerative). It would be bad enough if the practice merely resulted in higher costs, but it also hinders medical practice. Practitioners now have to search bloated documents filled with outdated or copied text in order to find relevant information. Inevitably, important details get overlooked.

A recent survey of more than 1,000 internists providing ambulatory care by the American College of Physicians found a statistically significant average loss of 48 minutes per clinic day (the equivalent of 4 hours per five-day week) due to EMRs. A third of respondents reported that it took longer to find and review medical-record data with an EMR than without. A similar percentage reported that it was harder to read other physicians’ notes in the EMR than it was to read them in the traditional written format. This echoes similar findings in a study of family physicians providing ambulatory care and an earlier study of non-federally funded, community office-based physician practices throughout the U.S. showing that EMRs were not associated with better-quality ambulatory care.

EMRs have also not delivered on the promise of making patient data easily available regardless of where the patient seeks care. Sixty percent of hospitals share electronic data with providers outside their system; only 14 percent of office-based physicians share data with outside providers. The types of information shared are limited because existing information technology systems aren’t standardized. A RAND report for the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology concluded, “The current lack of interoperability among data resources for EHRs is a major impediment to the unencumbered exchange of health information and the development of a robust health data infrastructure.”

Deficiencies in Texas Health Presbyterian’s EMR system were not the primary culprit behind the errant discharge of Thomas Duncan. But it’s possible, too, that the nurse would have had time to alert the physician that Duncan had just returned from Africa if she were not so preoccupied with entering data in the EMR. And it’s possible that the physician would have found this information if the chart wasn’t jammed with unnecessary notes. Finally, it’s possible that the physician might have obtained a more thorough patient history if he or she had spent more time with Duncan and less time with the EMR.