Diversity-training programs purport to teach participants how to be better colleagues to people from different backgrounds and to eliminate unconscious bias and make workplaces more welcoming. But in too many places, these trainings—and the broader DEI structures of which they are part—have instead mandated ideological conformity, enforced with the leverage every employer holds over its workers.

That’s why the U.S. Eighth Circuit Court’s en banc (all-judge) decision in Henderson v. Springfield R-12 School District matters. Over two years ago, I filed an amicus brief for the Manhattan Institute in support of the plaintiffs, but it took until the end of last month for the court to restore a basic proposition that DEI bureaucracies have tried to wish away: the First Amendment doesn’t stop at the HR department.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

In 2020, the Springfield, Missouri, school district ordered employees to attend a “Fall District-Wide Equity Training.” Participants were told to “lean into your discomfort,” “acknowledge YOUR privileges,” and “speak YOUR truth.” But the most revealing “guiding principle” was a warning that made clear what kind of “conversation” this would be: “Be Professional—Or be Asked to Leave with No Credit.” That “credit” wasn’t symbolic; employees understood it as tied to pay.

The training featured a slideshow and a series of cartoon videos about “systemic racism” and “understanding white supremacy.” Attendees were told that “systems of oppression” were “woven” into the “very foundation of America,” and that white supremacy is a “highly descriptive term for the culture we live in.” Trainees were directed to break into small groups to discuss these concepts before returning to a larger group discussion, where they were told that, if they didn’t speak, they would get called upon.

The district supplemented this program with online modules that were less discussion than catechism. Employees had to select preprogrammed “correct” answers. One screen instructed: “Incorrect! This is not suggested guidance. It is required policy and job responsibility.”

The training closed with an “anti-racist solo write,” in which trainees were expected to write out what steps they would take to become “anti-racist.” The point wasn’t to teach staff about applicable law but to get them to agree to contested ideological claims.

Two employees, Brooke Henderson and Jennifer Lumley, said they self-censored during the training and, in Henderson’s case, were compelled to adopt the district’s preferred answers. They sued. The district court dismissed their claims for lack of standing and then did something even more chilling: it charged them an eye-popping $312,869.50 in attorney’s fees for frivolous litigation. On appeal, an Eighth Circuit panel affirmed the dismissal but reversed the fee award.

The en banc Eighth Circuit reinstated the lawsuit, in a careful decision that should become a guide for similar challenges. Judge Ralph Erickson begins with a reminder: “It is important to note at the outset what this case is not about.” The court isn’t grading the district’s politics or even deciding whether all DEI trainings are unlawful, but whether the plaintiffs here alleged a real injury in which the government created conditions that predictably chill or compel speech.

On chilled speech, the majority recognizes what anyone who has sat through these sessions knows: “professionalism” is often a euphemism for not contradicting received orthodoxy. When a public employer warns that you can be denied credit for required training—and you reasonably infer that dissent will be treated as “unprofessional”—the pressure is not hypothetical. The court reiterates: “a plaintiff is not required to first suffer a consequence before she may bring a claim.”

On compelled speech, the opinion confronts the reality of those “correct answer” modules. A format that prevents employees from proceeding unless they pick the government-approved answer “forced acceptance or adoption of the school district’s views.” That’s the line between legitimate instruction and unconstitutional compulsion. Government can train employees on lawful duties and express its own views; it cannot demand that private citizens agree with those views as the price of employment.

Then there’s the fee award. Fee-shifting is supposed to be rare, because it turns civil-rights enforcement into a game of Russian roulette for the plaintiff. In one sentence, the court dismantled the district court’s attempt to make an example of these plaintiffs: “the standing issues presented in this case are by no means frivolous or groundless.” That matters as much as anything else here. DEI regimes don’t just chill speech in the training room; they chill it in the courthouse.

More broadly, Henderson is another important step in the pushback against DEI. It doesn’t outlaw training about discrimination. Nor does it forbid schools from pursuing equal opportunity. What it does—properly—is draw a constitutional line to prevent DEI demands from becoming ideological tests. As the majority puts it, “It’s about suppression of viewpoints.”

Public schools should model the robust exchange of ideas they claim to teach. They can’t do that while running mandatory programs that treat dissent as misconduct. The Eighth Circuit has now said: if you want employees’ agreement, persuade them. That’s how free citizens—and schools—should work.

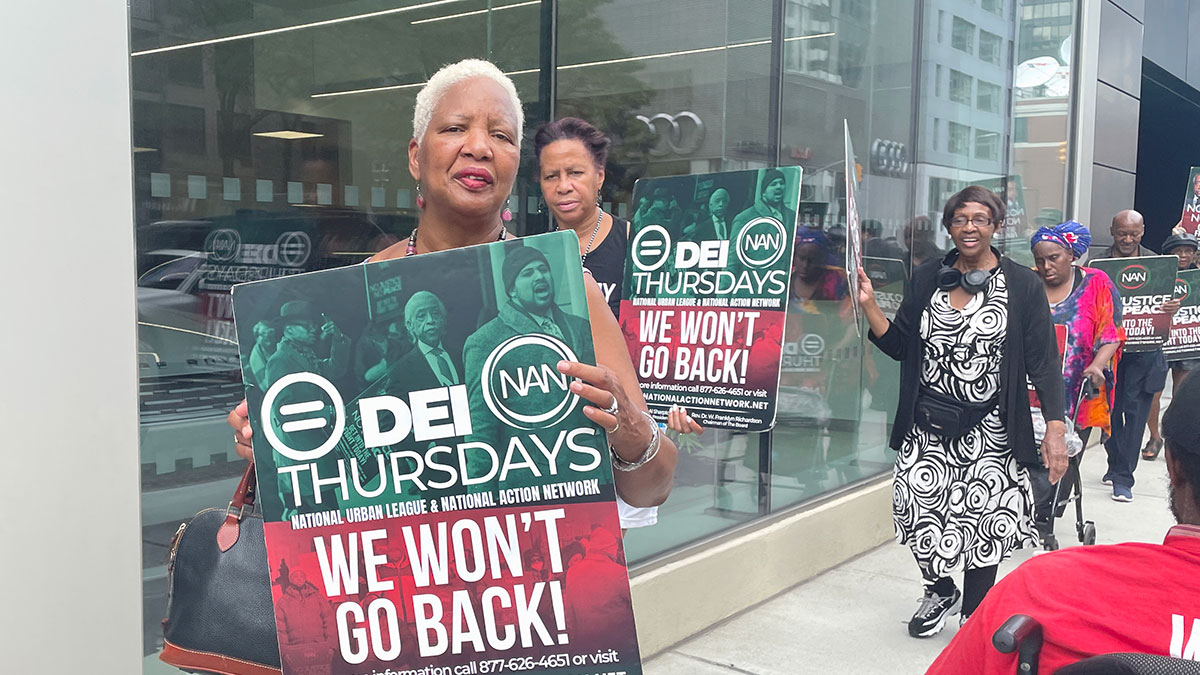

Photo by: Deb Cohn-Orbach/UCG/Universal Images Group via Getty Images