When a group of painters exhibited their bold new style in 1905, reviewers were traumatized. Repelled by the brash colors and the deliberate lack of perspective, one critic labeled them Les Fauves—the Wild Beasts. Another grumbled, “A pot of paint has been flung in the face of the public.” But over the next decade, the works of Henri Matisse, André Derain, Maurice de Vlaminck, Kees van Dongen, and other “wild beasts” were reappraised. The prices of their oils and watercolors doubled in value, then tripled, then exploded. Decades later came the ultimate tribute: Les Fauves were imitated not only by other painters but also by poster-makers, advertising agencies, and, in midcentury, by children’s book illustrators.

Leading the parade of art for juveniles was Ludwig Bemelmans, whose Madeline books have remained popular for seven decades. But the most daring and creative marcher was Miroslav Šašek, a writer-illustrator whose works have remained in the shadows since his death in 1980 but whose native Czechoslovakia (now the Czech Republic) has just begun recognizing his extraordinary achievement. For Šašek did something that no other popular artist had done. Beginning in the late 1950s, he wrote and illustrated a series of children’s travel books. In an epoch of discount jet fares for kids, this no longer seems unusual. But in Šašek’s day, it was unprecedented. Almost overnight, he became a literary celebrity. But his new fans knew little about him. Biographical detail was sparse, as Šašek preferred it.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Born in Prague in 1916, Šašek was one of two children. His father, a clerk, died young, and his mother insisted that he pursue an architectural career, over his objections that he wanted to be an artist. Šašek graduated from the Prague Polytechnic in 1937 but never practiced his profession. Instead, he survived World War II by contributing drawings to Czech periodicals and making plans for an artistic career. In 1947, Šašek journeyed to Paris to study painting at the École des Beaux-Arts. The next year, the Communists seized Czechoslovakia. With political and artistic freedom restricted in his native land, the artist opted for exile in Paris.

But the cost of paints, brushes, canvases, and easels rose by the month, and Šašek’s money was running out. After a frantic search for employment, he found work in Munich, headquarters of Radio Free Europe, funded by the U.S. State Department. Along with other Slavic refugees, Šašek wrote and read features in his native tongue. The programs, contrasting the assets of the free world with the liabilities of the Soviet Union, were beamed behind the Iron Curtain, where they won a wide audience. The young Czech worked in radio from 1950 to 1957, becoming a producer and acquiring a wife and young stepson along the way.

One day, between broadcasts, an idea came to him: Why not combine his admiration for modern “fine” art with his architectural training? There were plenty of books for the armchair traveler. Why not one for the high-chair tourist? In 1959, This Is Paris was born. With sharp wit and draftsmanship, Šašek brought new life and light to the standard tourist sites. He surrounded the Eiffel Tower with a brilliant fauvist rendering of buildings and churches, along with whimsical studies of a gendarme directing traffic; a shopper bringing home a baguette as tall as she is; and glimpses of the zoo, the Seine, and a cemetery for dogs. All these were explained in simple sentences that even preschoolers could comprehend. The book proved an international hit. Šašek followed it up with This Is London (1959), This Is Rome (1960), This Is New York (1960), This Is Edinburgh (1961), and, inevitably, This is Munich (1961). Yet he had barely begun. Bristling with nervous energy, he trotted around the free world, sketchbook in hand. Citizens and sites in Ireland and Greece became subjects for the thin, wiry artist with the face of a character actor and the hand of a master. When he brought his paints and paper to Israel, he remembered, “People laughed at me for hours the way I painted the signs. They couldn’t understand how I did them left to right when they read and write their letters right to left.”

But the United States remained Šašek’s greatest inspiration, with the Lone Star State making an especially rich subject. For This Is Texas (1967), he drew a store specializing in books and guns; a cowpoke on a violently bucking bronco; and oversize ranches, rodeos, and rattlesnakes. This Is Cape Canaveral (1963; later retitled This Way to the Moon) gave the author/illustrator a chance to present Enos the chimpanzee in an astronaut suit. Then Šašek did the unexpected: instead of just illustrating the rocket, he showed a vast assemblage of space-watchers, with their long-range lenses pointed at Apollo 11 on its lunar journey. “Detail is very important to children,” he told an interviewer in 1969. “If I paint 53 windows instead of 54 in a building, a deluge of letters pours in upon me. Children today know everything—the world is much smaller.” He related his stepson’s observations as the boy examined Šašek’s sketchbooks for the volume on space. “Without a word from me, he mentioned that this is the Apollo rocket and this is the launching pad. I could not believe it! Sometimes I cannot believe the children of today. When I was a youngster, no one traveled.”

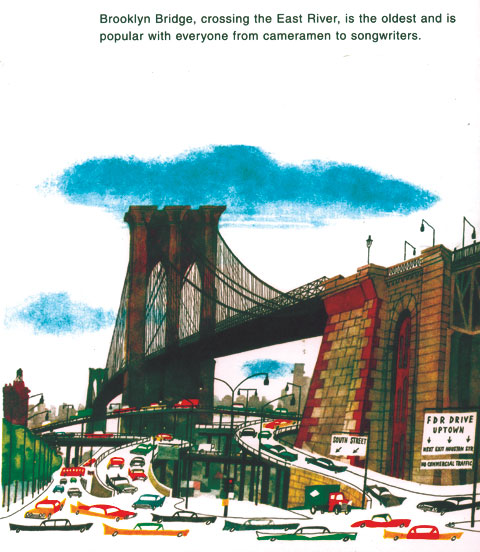

This Is New York showcased Šašek’s sense of the absurd. He illustrated the rectangular skyscrapers throwing shadows over Manhattan, depicted the rotund new Guggenheim Museum—and then juxtaposed them with a hot-dog stand, a small boy feeding a squirrel in Central Park, and a cluster of picketers on strike.

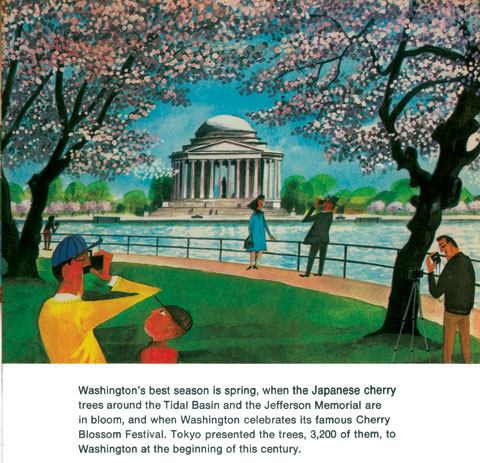

He arrived in the nation’s capital at the worst of times, shortly after the assassination of Martin Luther King. “It was like a continuing nightmare,” he told an interviewer. “It was worse than Berlin in 1945! The riots were especially terrible to witness. One day while I was sketching the grave site of John F. Kennedy, the guards told me that I would have to leave; moments later trucks and crewmen appeared, to dig the grave of Robert F. Kennedy. I could not believe these tragedies, one after the other.” Even so, he was awed by the White House, the Lincoln and Washington Memorials, and the neoclassical architecture all around him. In This Is Washington, D.C., Šašek celebrated the nation’s history even as he mourned its martyrs.

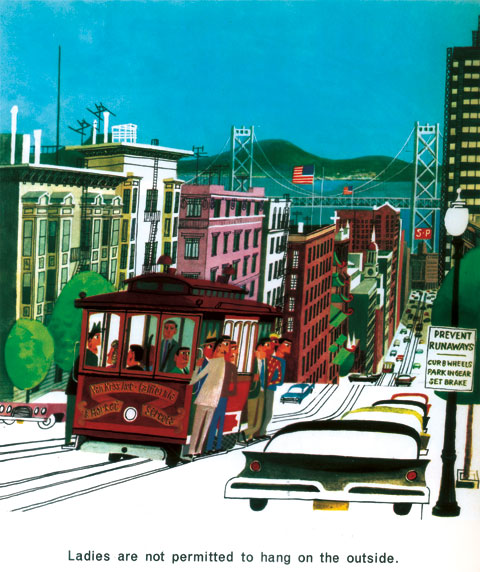

This Is San Francisco was a different book entirely. Here was a city like no other, on either side of the pond. He showed his readers the steep rolling hills, the cable cars that traversed them, Golden Gate Park and its clusters of trees, Chinatown—offering exotic foods whose aromas seemed to rise from the page—the Presidio, Alcatraz, and Fisherman’s Wharf, all under the sometimes-foggy, often blue-skied ornament of northern California. Like many another visitor, the artist found but one fault in San Francisco: it was “hard to leave.”

Eventually, Šašek supplied juvenile readers with guidebooks to Australia, Hong Kong, and even the United Nations and historic Britain. By the early 1970s, he was divorced and living in Paris, where he continued to work, celebrating toy trucks in his Mike and the Model Makers (1970) and providing his distinctive illustrations for other authors’ books. Royalties and honors piled up. Short film adaptations of This Is New York, This Is Israel, This Is Venice, and This Is Ireland were made for schoolchildren. This Is London and This Is New York topped the New York Times Best Children’s Books of the Year in 1959 and 1960. Šašek received the Boy’s Club of America Junior Books Award, and This Is the United Nations made the International Books for Young People Honor List. The great British compendium, Children’s Picture Books, appraised the This Is . . . series: “The simple formula of playful visual tours of cities around the world has led to the books achieving classic status.”

Welcomed in dozens of nations, Šašek considered France his home country. Yet he never applied for citizenship. Though his books were published in more than a dozen languages, including Japanese and Greek, he chose to remain stateless to the end. That end came suddenly in 1980, when he suffered a fatal heart attack while visiting his sister in Switzerland. Thousands of children’s books were published over the next decade, and the name Miroslav Šašek dropped into the out-of-print bin of history. But his fans had long memories, and in the 1990s, Rizzoli began reissuing the This Is . . . books. A new interest was ignited.

In addition to volumes about cities and countries, postcards and posters of Šašek’s work have now become available as well. Even more encouraging, Baobab, the Czech publishing house, is bringing out the works of its countryman, as if to compensate for the decades of deliberate neglect. Leading the list, once again, is This Is Paris. It is extraordinary for any book—especially a children’s book—to enjoy a renaissance 55 years after its first appearance. But then, Miroslav Šašek was an extraordinary talent. Curious readers can see for themselves: some 20 reasonably priced volumes can be found on the Internet. Bet you can’t read just one.