Football, by Chuck Klosterman (Penguin Press, 304 pp., $32)

You will probably watch the Super Bowl on Sunday. Maybe you’re a casual fan. Maybe you’re a football nut who wants to see how New England’s defense matches Seattle’s heavy formations. Maybe you just want to watch the commercials.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Whatever your motivation, you’ll have company. More than 191 million people tuned into the Super Bowl in 2025. Americans are projected to spend more than $20 billion on game-related food, drinks, gear, and more this year. Many households observe the Super Bowl more reverently than Easter.

The Super Bowl is popular because football is popular. Seventy of the 100 highest-viewed American television events in 2024 were NFL games. Football is a mother tongue among American men; walk up to five guys in a random city and at least three will have a coherent opinion about Bill Belichick’s contribution to the Patriots’ dynasty.

In Football, Chuck Klosterman argues that despite its popularity, the sport is doomed. He claims that America, which today shells out billions for NFL tickets, will eventually consider the game an anachronism, like jazz or indoor smoking.

Most people who make this kind of argument hate football. Klosterman has conceded as much. But he loves the game; he played it, watches religiously, and—in the book’s best paragraph—admits to sitting in his kitchen late at night imagining coaches discussing how to block backside edge defenders. He sounds like a lunatic, but it makes him credible. It's a must-read for football obsessives who want to understand why they love the game and for outsiders who want to know what they're missing.

Klosterman constructed the book as a series of essays, only one of which is dedicated to football’s future. Other entries discuss the game’s greatest player (Jim Thorpe), the archetypal football coach (who understands that the “old ways . . . continue to work”), race (“How many NFL quarterbacks should be [b]lack?”), and more.

“Football,” he writes in an essay on the game’s appeal, “aspires to petroleum engineering.” No sport with those aspirations would seem to have any business being so popular. But football has become America’s most popular sport—consumed by diehards and casuals alike—partially because of its complexity.

Football has the best athletes and is the best game. If Klosterman is right about the game’s decline, America will someday lose touch with the crown jewel of global sports.

Football is popular for two reasons. The first is its athletes.

Every professional athlete is a “good” athlete in a tautological sense: professional sportsmen are professionals, after all, because they’re talented enough to play professionally. But this isn’t how most people think of athleticism.

Most people consider athleticism a scalar quality. Hockey requires more athleticism than bocce. Volleyball is more demanding than ping pong. The second-best basketball player at your local YMCA is probably a better athlete than each of the last ten PDC World Darts champions.

Athleticism involves three traits: raw physical talent (strength, speed, and explosiveness); fine motor skills (coordination, body control, sport-specific tasks like catching and throwing); and applied ability (using those raw gifts and refined skills in the context of competition). And no sport requires more athleticism than professional football.

Take Julio Jones, the five-time All Pro wide receiver who retired in 2023. Any number of players could serve as an example, but Jones is one of the best American athletes of the 2010s. You couldn’t create a better athlete in a laboratory.

Jones is 6’3”. He played at 220 pounds and wore it like a prizefighter. At the 2011 NFL Combine, he ran a 4.39-second 40-yard dash (within 0.2 seconds of Usain Bolt); standing-broad-jumped 11 feet 3 inches (within shouting distance of the unofficial world record, set by another NFL player); and posted a 38.5-inch vertical leap (higher than any professional basketball player at the NBA combine in the past four years). And he did all this with a broken foot.

Jones had world-historic physical gifts. If those were the extent of his talents, he would have made a fine track athlete. But Jones was a football player, and regularly did things like this against other professional football players:

This Julio Jones grab. 😱

— NFL (@NFL) March 29, 2020

Rewatch Super Bowl LI, today 3pm ET on @NFLonFOX. pic.twitter.com/MYQurNRCgJ

This is peak coordination. Jones runs a “post-corner” route, sprinting vertically for ten yards, cutting inside for five, and breaking back toward the sideline. His quarterback, Matt Ryan, puts the ball just beyond the grasp of Patriots defensive back Eric Rowe. If no one had touched the ball, it probably would have landed out of bounds.

But Jones had other plans. Off the out-break, Jones stops, leaps with arms outstretched, corrals the ball, impossibly taps both feet in bounds, and completes the catch. There may have been six people on Earth at the time who could have done this, five of whom played in the NFL.

Jones’s physical gifts were necessary, but not sufficient, to make the catch. Watch a slightly longer clip of the play here. Right before the ball is snapped, Jones (bottom of screen, Number 11) gets set after coming in motion. Rowe (Number 25) followed him there across the field, giving Jones a clue about how the Patriots planned to cover him.

As Jones runs the “stem” of the route (the vertical sprint) he sees a safety coming over to help Rowe in coverage. Given that no other Falcons receiver is threatening the safety, Jones sells the in-cut to avoid a potential double-team. His fake turns the safety all the way around, and when Jones cuts back outside, he has a one-on-one matchup with Rowe, which he wins. To get himself open enough to catch this ball, Jones needed to understand his route, his teammates’ routes, and the opponents’ coverage—in real time.

Other games are more demanding than football in some respects. Track-and-field requires more explosive speed. Baseball arguably demands more precise fine-motor skills. But no sport requires the same combined explosiveness, coordination, and athletic intelligence as football.

It’s one reason viewers simply can’t turn it off.

The other reason is counterintuitive: football’s disjointed gameplay creates a better product.

In 2010, the Wall Street Journal reported that the average NFL broadcast features just 11 minutes of actual football. While commercials, in-game stoppages, and halftime are partially responsible, lags are built into the game itself. Players often spend more than 30 seconds huddling up, relaying the call, and shifting around, only to run a play that, snap-to-tackle, takes about six seconds.

You would perhaps expect viewers to lack interest in a disjointed game compared with a constant-action sport like soccer or hockey. But Klosterman argues that 11 minutes is actually the ideal amount of action:

The intermittent moments of nothingness add to the pleasure. You can hold an entire conversation by talking in between plays without losing focus on the game itself. You can think about what you just saw or what might happen next. You can check your phone or drink a beer or daydream about something completely unrelated. Your mind can relax without detaching from engagement.

“[S]tructurally,” football is a “halting and cerebral” sport, Klosterman maintains, with huddles to strategize and chess-like battles between offense and defense before the snap. But for the six seconds the ball is in play, as players run high-speed routes and suffer high-impact collisions, “it feels like watching something that’s too fast-twitch to comprehend.”

Football’s “halting” structure creates an outsize role for coaches. The ability to huddle turns the coach from a peripheral figure to a main character. A football coach can, in theory, dictate where all eleven men go on every snap.

For some critics, the coach’s influence is one of their biggest gripes with football. Klosterman cites an essay by art critic Dave Hickey, “The Heresy of Zone Defense,” in which Hickey accuses coaches in another sport, basketball, of being interlopers who impose needless structure on an improvisational game.

The “patriarchal cult of college-basketball coaches and their university employers,” Hickey claims, “have always wanted to slow the game down, to govern, to achieve continuity, to ensure security and maintain stability.” These coaches force “gifted athletes to guard little patches of hardwood in static zone defenses.” What Hickey believes, in Klosterman’s gloss, is that “the rules of basketball (and almost anything else) should not attempt to govern, but to liberate.”

Klosterman calls the essay “among the finest . . . ever written about any sport.” It’s not. Hickey effectively endorses a kind of chaos that, taken to its logical conclusion, would make sports unwatchable. Klosterman concedes that almost every sport to embrace Hickey’s thinking has “evolved away from its central identity.” Witness an anarchic three minutes in the second quarter of any modern NBA game—lazy passing, little offensive structure, sloppy defensive rotations—and you see the fruits of “improvisation.”

Professional football, by contrast, rejects Hickey’s logic. Players are part of a team. Coaches are leaders of those teams, with systems they expect players to execute. If players decide not to execute, coaches will find someone who will. As a result, the average NFL play is exceedingly complex—yet highly watchable.

Take this touchdown from a Week 2 regular season game between the San Francisco 49ers and the Cincinnati Bengals from 2019:

Opening drive results in this @JimmyG_10 to @marquisegoodwin 38-yard touchdown 👏#GoNiners pic.twitter.com/TgoCV6Ct7j

— San Francisco 49ers (@49ers) September 15, 2019

Dozens of things are happening here. As Klosterman notes, “Describing how NFL football transpires on a play-by-play basis is like trying to explain the incremental mechanics of a nuclear reactor.” Here’s a shot at it.

At the snap, San Francisco’s offensive line, tight end, and running backs step in unison to the left side, simulating an outside zone run. Cincinnati’s defensive line and linebackers rush to fill vacant running lanes and “outflank” (beat to the sideline) the offensive linemen and tight end. San Francisco’s quarterback, Jimmy Garappolo, extends the ball and appears to hand it off to running back Matt Brieda.

But it’s a fake. Garoppolo yanks the ball away. Fullback Kyle Juszczyk winds back to block the uncovered defensive rusher. The quarterback appears poised to execute a staple of the 49ers playbook: a crossing route opposite the fake-run side and the duped defenders.

Cincinnati’s secondary was prepared. The Bengals played man-to-man coverage with a deep safety. They likely watched San Francisco run similar “boot-action” passes on film, remembered the coaching point, and stayed with their men on the backside of the run fake. The 49ers, however, presented the boot action as yet another fake, and hit a wide open receiver, Marquise Goodwin, on the run-fake side for a touchdown.

This level of complexity is present on every NFL snap—and every snap matters. Unlike professional basketball, where teams get more than 100 possessions per game, NFL teams may get only ten chances to score. As Klosterman notes, every play is consequential. Every yard counts, and every shift, disguise, and bluff is meant to get an advantage at the margins, where football games are won and lost.

The very existence of the huddle means that coaches matter more in football than in other sports. If the AFC-winning New England Patriots had been led by a random college coach instead of Mike Vrabel, they might not have made the playoffs, let alone the Super Bowl. If manager Dave Roberts had never come to the ballpark, the Los Angeles Dodgers would still have won the World Series.

Football is often compared with war. Players take orders and execute commands. They consider the team more important than the individual. They push their minds and bodies to the brink in pursuit of victory.

Ironically, America, which adores football, increasingly encourages the opposite approach. We want our athletes to improvise, to avoid injury, and to “get theirs” when it’s time to get paid. The ethos of the country and of its favorite sport seem to be on a collision course.

Two forces will lead to football’s eventual decline, Klosterman believes. The first is advertising revenue. The NFL makes more than $5 billion in estimated television advertising revenue annually. At some point, he argues, advertisers will realize that advertising doesn’t work and will simply stop spending money on television spots.

The second is cultural. As fewer Americans let their children play football—citing worried about concussions and other injuries—and the country’s values diverge from the sport’s, the game will become an anachronism. Football “will never completely disappear, in the same way you can still hear jazz on NPR and you can still smoke Lucky Strikes inside a casino.” But it will no longer be central to American life.

Even if his prediction proves out, doomsday is a long way off. But the game’s would-be saviors would do well to remember Klosterman’s observation: “Football flourishes by making freedom impossible.”

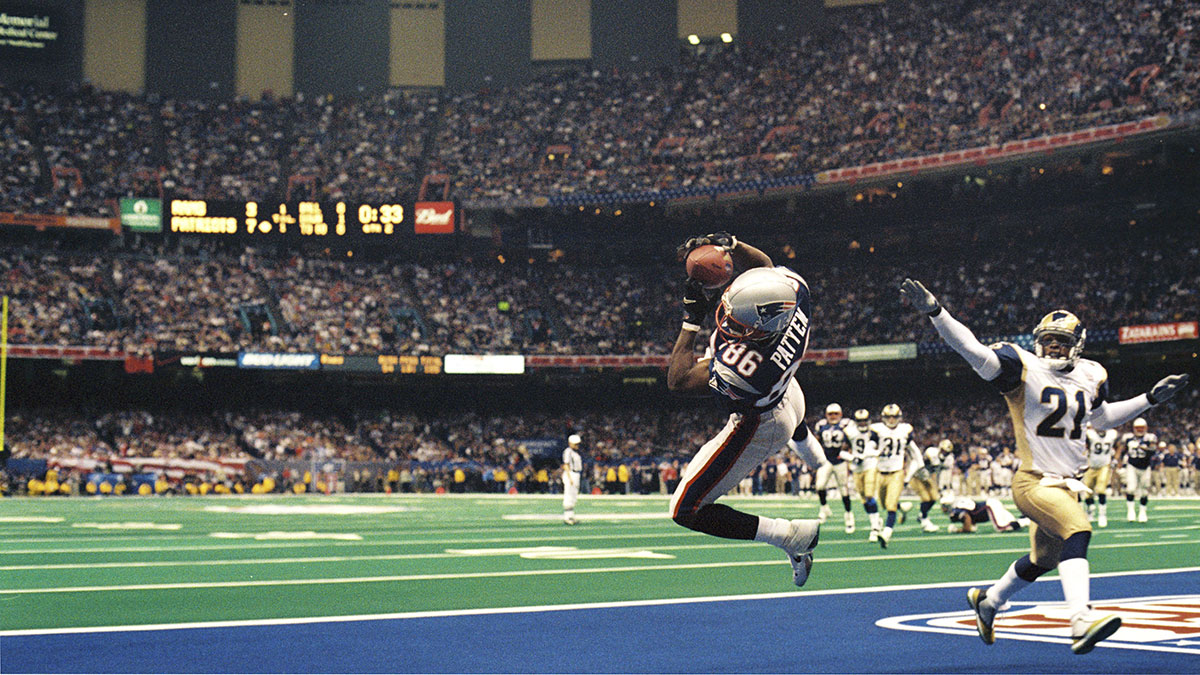

Top Photo: David Patten of the New England Patriots catches the ball during Super Bowl XXXVI in 2002. (Photo by Allen Kee/Getty Images)