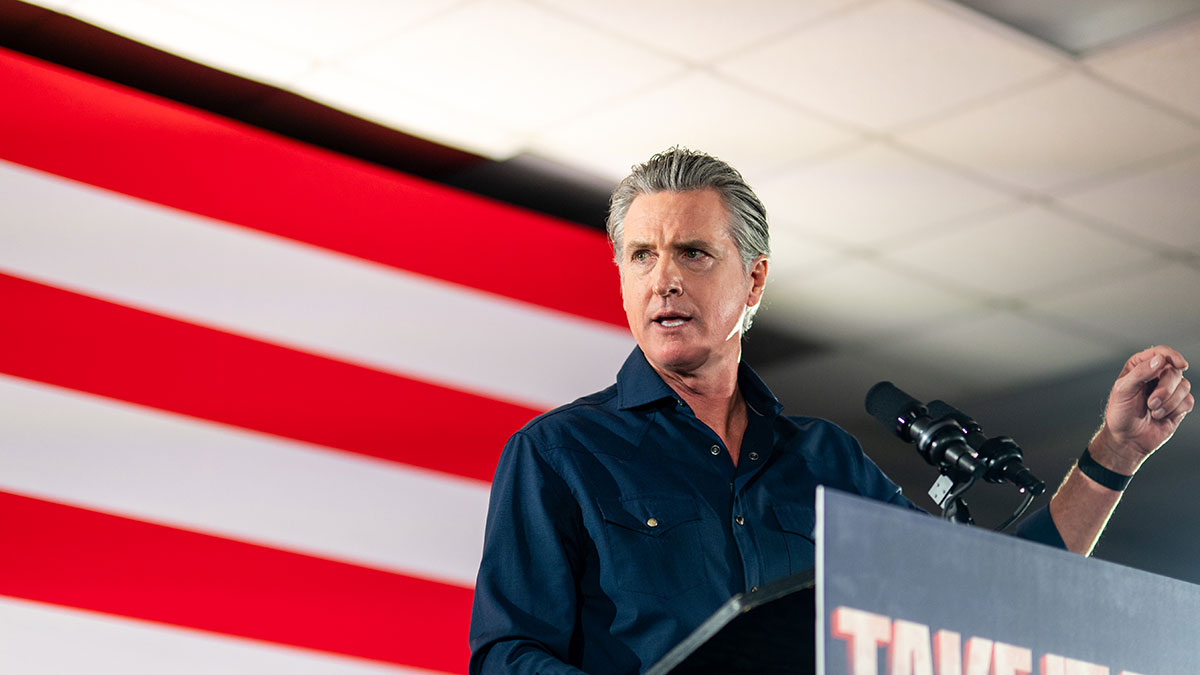

In a state facing a long-term budget crisis, massive out-migration, and the nation’s highest poverty and unemployment rates, you would think that voters would want to throw the bums out. But this November, Californians are poised to elect a new governor who will be, if anything, more irresponsible than Gavin Newsom.

The Golden State is in for a competitive primary. Kamala Harris and Senator Alex Padilla have declined to run, opening the door for a relative unknown to seize one of the nation’s most important executive offices. The current uninspiring field is enough to make one yearn for the days of cranky-but-smart Jerry Brown, or even of the opportunistic chameleon Newsom.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

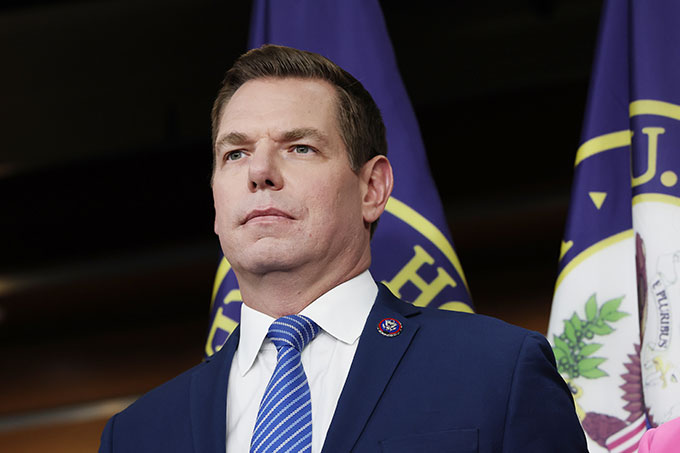

The leader in the most recent Emerson poll was, of all people, Congressman Eric Swalwell, whose biggest asset is his anti-Trump reputation. That’s about all he offers; Swalwell is hardly a serious thinker or legislator. His greatest claim to fame, outside of repeatedly calling for Trump’s impeachment, is his former relationship with a Chinese woman, who, unknown to him at the time, may have been one of Beijing’s spies.

Slightly behind Swalwell in the polls lurks former representative Katie Porter. A law professor and long-time Elizabeth Warren acolyte, Porter is a far more serious type than Swalwell. Her mildly anti-Israel politics and her fondness for redistributive policies could have played well with the state’s Democratic primary electorate. But televised outbursts and her ex-husband’s nasty testimony about her conduct have undermined Porter’s candidacy.

Big-spending billionaire Tom Steyer has also thrown his hat in the ring. Steyer, who made much of his money investing in fossil fuels and private prisons, has morphed into a full-time environmental zealot and a hardline defender of the state’s climate regulatory regime. His entrance into the race is manna for consultants, as he will inevitably spend a fortune to promote his candidacy, now lagging at under 5 percent support.

Steyer’s focus on climate issues, which climate fanaticism plays well with the media and college crowds, may be less popular among working- and middle-class voters. Most assessments, including from government sources, suggest that higher energy prices hit poor communities hardest.

Attorney General Rob Bonta is reportedly considering getting into the governor’s race. A progressive and recent subject of scrutiny about his use of campaign funds to pay attorney fees in a bribery investigation, his entry could reshape the race. As overseer of the state’s legal resistance to the White House, he has sterling anti-Trump credentials. And he has supported the creation of a wealth tax, which will doubtless appeal to the state’s increasingly radical Democratic primary voters.

Largely missing from the race is a moderate, business-oriented Democrat willing to challenge the ruling cabal in Sacramento. One potential reason is the influence of the California Teachers Association. The union funded much of Newsom’s successful redistricting drive. The only prominent Democrat willing to fight the teachers’ union—former L.A. mayor and teachers’ organizer Antonio Villaraigosa—hasn’t won over California’s business elite. He’s also stuck at 5 percent.

Perhaps the most viable hope for a course correction is the potential candidacy of L.A. real-estate mogul Rick Caruso. Sacramento desperately needs his business skills. But Caruso’s 2022 run for mayor of Los Angeles against Karen Bass was a disappointment. Current talk suggests he’s keen on a rematch, not a gubernatorial run.

How about the Republicans? Center-right candidates should be viable in the Golden State. After all, most Californians, according to a UC Berkeley poll, think the state is headed in the wrong direction, and Newsom’s approval rating hovers around 44 percent.

Yet so weak is the GOP brand that Democratic political strategist Paul Mitchell told me that he believes no Republican—or even a moderate Democrat in the Caruso mold—has a clear path to victory. The bulk of Democratic primary votes comes from deep-blue, left-leaning districts in places like San Francisco, Los Angeles, and San Jose. These are also favored spots of a Zohran Mamdani-like constituency of underpaid, underemployed, and overeducated professionals.

For now, the GOP has two relatively serious candidates: former Riverside sheriff Chad Bianco and one-time Fox commentator Steve Hilton. Bianco, GOP national committeeman Shawn Steel observed in a conversation, seems perfect for the Trump base. Hilton, despite his genuflections to the president, offers a pragmatic, problem-solving approach à la former governor Pete Wilson. Together, they are polling around 25 percent, a number that could grow as the Democratic candidates’ far-left bend becomes more obvious.

But unless Democrats splinter their votes among several candidates, the GOP’s chances are roughly comparable with those of a major snowstorm in Santa Monica. Republicans can count on barely one in four California voters; Democrats hold close to half. In most statewide elections, the GOP wins under 40 percent, about what Trump received in 2024. A Republican has not won a statewide race in almost two decades.

Indeed, the party’s only hope, suggests long-time GOP pollster Arnie Steinberg, is if somehow the Democratic vote were so fractured that the two Republicans come up on top in the state’s top-two “jungle primary” system.

“This is the only way they can win,” jokes Mitchell. “Californians would vote for a dead Democrat over a live Republican.”

Until Californians recognize that Sacramento, not Trump, is failing them, leftist politics are likely to remain dominant in the Golden State. Newsom, constrained by his presidential ambitions, at least had the sense to rebuff the powerful green lobby’s more unreasonable demands, allowing the state’s once-massive oil industry to remain active and preserving its last nuclear and natural gas plants. He has also opposed the wealth tax, a policy that would have been catastrophic for a state that relies on its high earners.

But soon, Newsom’s presidential aspirations will no longer constrain Sacramento. Under a more assertively progressive regime, the state could reinforce its already-stringent climate regulations while boosting taxes even higher. It may take Sacramento breaking the proverbial backs of California families for the Golden State to see real change.

Top Photo by Brandon Bell/Getty Images