From the appetizing smells and disciplined, busy cooks, you’d think it was the kitchen of a bustling restaurant, filled with diners. But with no tables to reserve, no serving staff, and just a discreet entrance, where Uber Eats and Deliveroo drivers (the only clientele this kitchen serves) pick up orders, this is a “dark kitchen,” bringing together chefs and their wares with online search and food-delivery platforms—businesses based on software, data, and proprietary networks of drivers. These technological platforms make delivery-only restaurants more viable, opening opportunities for entrepreneurs who identify neighborhoods lacking, say, a good brick-and-mortar Thai eatery and meeting the demand for such food. The dark kitchen is an example of a tangible institution (the restaurant) adapting to an increasingly intangible economy—and it’s emblematic of the most important economic shift of our time.

The emerging economy is often described as technological, an economy based on the Internet or Big Data or whatever is on Wired’s cover this month. But it’s really about a deeper change: a long-term shift in the nature of capital, from physical assets to intangible ones. Like all major economic transitions, the shift is painful and disorienting, in part because it is unevenly distributed. While some companies, regions, and groups are deeply involved with the new forms of production, many others are not, and the left-behind aren’t just the disadvantaged populations of declining areas (though they’re certainly struggling) but also some of the world’s wealthiest firms.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Our future prosperity will depend on whether a critical mass of companies, public and private institutions, and people can adapt to the new economic realities—and unleash a new age of productivity growth.

As documented in our 2017 book Capitalism Without Capital, recent decades have seen a steady alteration in the developed world’s capital stock. Once, firms mostly invested in physical stuff: machines, vehicles, computers. As society gets richer, though, more and more business investment goes toward things you can’t touch: research and development, branding, organizational development, and software. The change is not just the result of information technology; the data show that it began well before the Internet. Indeed, as far as we can tell, the shift seems to be a long-term trend: as economies get richer, intangible investment becomes more important.

Intangible capital behaves differently from the physical kind. For starters, it is highly scalable. Think of an algorithm: nothing in principle prevents it from being used by anyone with access to it. Intangible capital also has spillover effects: a business investing in R&D can’t be sure that it will enjoy the exclusive benefit from its investment, since rivals can copy it. And it is a sunk cost—if a business fails, its intangible assets are rarely worth much to creditors. Finally, intangible assets are often massively more valuable when combined.

The dark kitchen is a striking example of the power of intangible capital. Formerly space-dependent, the restaurant industry is increasingly shot through with invisible networks: delivery aggregators, by efficiently linking customers to kitchens and drivers, offer new paths to commercial success.

Intangibles give rise to five major trends that mark today’s economy. The first: the growing importance of clustering. Economists have long known that people prosper when they come together to exchange ideas. What’s new is that the benefits of being in dynamic cities have increased, and the advantages show up across industries. The Bay Area, once a semiconductor cluster, is now home to a host of only tenuously related successful industries. The “triumph of the city,” as Harvard economist Edward Glaeser has called it, looks ever more complete.

A second characteristic is a dramatic transformation in the nature of economic competition. For the last few decades, the gap in profitability and productivity between leading firms and the rest in all industries and countries is widening. Emerging research that we’re helping to conduct reveals this gap to be greatest in the most intangible-intensive sectors—presumably because scale and synergies play to the leading firms’ strengths. This trend has a significant human impact: census data suggest that it explains more than three-quarters of the rise in American income inequality in recent years. But alongside this leading-firm phenomenon, one also finds instability. From time to time, the dominant firms get completely disrupted by fast-growing, highly scalable new businesses. Competition begins to look less like an ongoing battle for market share and more like a series of reigns, punctuated by occasional revolutions.

The third economic trend is greater contestation. It’s harder to prove who owns intangible things than tangible things, so we see more high-stakes rivalry and litigation around what belongs to whom—and even whether certain things should be owned at all. These disputes are familiar in the tech sector. What are Uber’s obligations to its drivers? To what extent should YouTube respect copyright? But the conflicts are becoming ubiquitous. Can libraries lend eBooks? Should farmers be able to repair their own tractors? Contestation inevitably increases the economic returns of political power, which can shape the legal environment favorably.

Because intangible-intensive firms often lack collateral (factories, fleets, and so on) and are less attractive to debt financiers, as the intangible sector grows—and this is a fourth trend—the financial systems of developed economies are becoming less suited to the needs of businesses. Economist Stephen Cecchetti calls this the “curse of collateral.”

The fifth development is what we call the community paradox. Because of the synergies of intangibles, people with strong networks of contacts are well placed to thrive in the emerging economy. At the same time, the disruption caused by the rise of intangibles tends to weaken the bonds of social trust that form the basis of these networks. To borrow Geoff Mulgan and Alessandra Buonfino’s striking phrase, we’re increasingly like “porcupines in winter,” aware of the fundamental importance of community as well as the growing barriers to achieving it.

These trends can be felt throughout society—but some players have mastered the new landscape more successfully than others. We’ve talked about the intangible economy with everyone from investors and startup founders to government officials and property developers. For some, especially venture capitalists and tech firms, the reaction was familiarity: “Of course, this is how the world now works.” Traditional industries and institutions, though, were more likely to express concern or resignation: “Fine, but if we’re not Amazon or Andreessen Horowitz, what can we even do about all this?” In our respective jobs in government and central banking, we see similar apprehension: many institutions in wealthy countries are unprepared for the economic transitions under way. This is true at the individual level, too. Large populations in developed nations—in some cases, constituting whole towns or regions—have been left behind by the shift; they regard the economic universe of brands, ideas, and R&D as foreign to their lives, as something involving other people. While many of those out of step with the intangible economy are struggling economically, this isn’t simply a story of the weak and the powerful. Among the institutions and businesses wedded to older ways of doing things are some of the world’s most venerable, including big banks and restaurant chains, and some people out of sync with the intangible economy are asset-rich.

Some older industries are starting to adapt, however. Consider CloudKitchens, a Los Angeles–headquartered company that builds and runs dark kitchens like the one we described. In one sense, the company is part of the old economy: it owns costly physical assets, things you can see and touch, like ovens and freezers. Yet it also taps into intangible-economy potentials and, by doing so, hopes to prosper in ways that strictly traditional restaurants cannot. Utilities are racing to invest in “smart metering” and technology that turns “dumb” pipes into intelligent-detection systems. Startups want to deploy manufacturing capacity as a service for customers with designs to build. Even some government bodies are catching on.

It’s crucial that more organizations, public and private, follow. After all, the more people and institutions that take part in the intangible economy, the more prosperity will grow. A city that can attract high-growth, scalable businesses will generate more and better jobs than one that cannot. A firm that can take advantage of intangible assets can realize greater profits. An individual with the skills and motivation to get ahead in the new economy will escape unemployment or low pay.

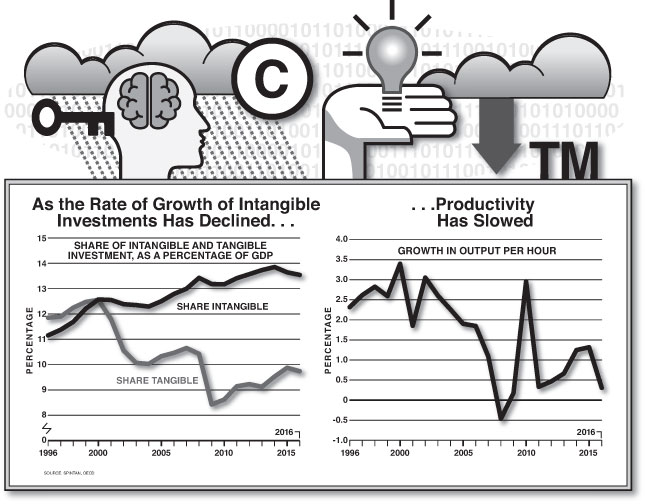

And important second-order effects would ensue. Since the 2008 financial crisis, investment in intangible assets is noticeably slowing. We know that productivity growth has been weak since the crisis, especially that part of it that economists call “total factor productivity”—and that’s exactly what one would expect to be hit by a reduction in spillover-rich intangible investment. Given the economic and social effects associated with sluggish productivity growth—from wage stagnation to political alienation—this is bad news. The risk is a kind of impoverishment trap. If a significant part of the population has little to gain from the intangible economy, democratic governments will be less inclined to take steps to help expand it, or worse, they may actively hold back its development. That would mean that fewer people will reap its benefits, tightening the trap.

The trap can be politically congenial. In the United Kingdom, a viable coalition has formed of economically and educationally disadvantaged voters in places that the new economy has bypassed and affluent older voters, whose financial well-being is largely insulated from slowing productivity growth. This coalition helped win the 2016 Brexit vote and will be the force that Conservative prime minister Boris Johnson will count on in the next general election. Whatever one’s views on Brexit, these voters tend to endorse certain policies that hinder the advance of the intangible economy, including reducing the numbers of foreign students and opposing zoning reforms that would help dynamic cities grow. Assembling this coalition may be smart politically, but by potentially dampening prosperity, it could do a disservice to the long-term vibrancy of the nation.

Escaping the impoverishment trap should be a paramount concern for governments, businesses, and other institutions. The dark-kitchen approach has implications for places that remain excluded from, or insufficiently aligned with, the intangible economy. It’s easy to see which places are doing well, and which aren’t. Larger, wealthier cities with lots of educated residents have boomed, creating abundant jobs and drawing people from around the world. Less well-advantaged or smaller cities—especially those that once depended on now-vanished manufacturing or mining concerns—often struggle, and their inhabitants often suffer, too, or move away. The divide between dazzling, expensive London and Lincoln, a declining city once home to industrial giants, or, in the United States, between, say, thriving big-city San Francisco and low-wage, high-poverty Fresno—among many other similar contrasting examples—gets more pronounced by the day. The intangible economy sharpens these divides by making agglomeration effects—the economic advantages of big cities—stronger.

The proposals of politicians and economists to close such divides mostly fall short. One prescription is for poor cities to make themselves more like successful ones by investing in public assets like universities and education, hoping that the tide that lifted San Francisco will buoy them, too. This approach has had some successes: Pittsburgh and Manchester, England, have gone from bywords for postindustrial decline to, if not rich places, then at least cities that people are optimistic about. (See “A Renaissance Runs Through It,” Summer 2019.) But smaller municipalities can’t benefit from agglomeration effects to the same extent.

Other proposals look to restore the lost industrial past. Perhaps if governments invest in industrial skills-training and building projects in struggling towns, the argument goes, the glory days of productive manufacturing firms and their well-paid jobs will return. This advice is politically appealing, but it’s not evident that it works in practice. Governments have a poor track record of creating jobs directly, and the local beneficiaries of training programs often leave and take their new skills to where more of the jobs are.

What is needed, in our view, are policies that fit the way that the economy now works—and that means policies adapted to intangibles. One step would be to connect smaller, less successful cities to larger flourishing ones. Many deprived towns are relatively close to successful major cities but lack the transport links to take advantage of the proximity. In Britain, Wigan—a symbol of hardship since George Orwell’s days—is as close to Manchester center as many of London’s affluent suburbs are from the center of London, for example; yet traveling from Wigan to Manchester is much harder, so the smaller metro doesn’t access similar opportunities. Improving transport from the periphery to the big city should be a priority for anyone who cares about down-on-their-luck places like Wigan.

A second option is to try to learn from those locales outside of cities that have done well in the modern economy. An unusual example in Europe is Mondragan in the Basque Country, home of the 60-year-old Mondragon Corporation, a workers’ federation and business group that owns banks, stores, and manufacturing businesses and employs more than 70,000. The Mondragon Corporation’s cooperative organization has made it a poster child for the Left, though it was founded by a Catholic priest and is, in many ways, a red-blooded capitalist undertaking, competing vigorously in various enterprises, including supermarkets, well beyond the Basque Country. Its success is striking for its emphasis on intangibles: it invests heavily in technical training and R&D, even running its own schools and worker-development centers. The corporation’s overarching structure seems to encourage the internalization of the spillovers of such investments and to mirror some of the agglomeration effects that big cities enjoy.

A third way to help smaller or less successful cities benefit from intangibles involves communications technology. The density of big cities helps them prosper because important business interactions still happen mostly face-to-face, and labor markets remain mostly local. Futurists predicted that new technologies meant the death of distance—that “knowledge workers” would soon disperse and telecommute from wherever they liked. That has signally failed to happen. Yet the economy’s biggest technological upheavals often occur after they’ve been widely dismissed as hype. A classic example: the electrification of industry happened decades after the invention of the original technologies; business practices and factory design had to catch up with the explosive new possibilities. We may be at the onset of this type of alteration with remote working. As economist Matt Clancy observes, new generations of workers are using tools like Slack to collaborate more effectively online. Seemingly frivolous ephemera of the Internet age like emojis and the abandonment of full-stop punctuation—skeptics like Robert Gordon see them as proof of modern tech’s economic insignificance—could represent hesitant, but increasingly viable, attempts to replicate at a distance the emotional bandwidth of face-to-face communication. A government worried about smaller cities should therefore invest in, or incentivize investment in, test beds and programs dedicated to quickening the death of distance, which might include the greater deployment of rural broadband or rolling out remote working technologies aggressively in government agencies.

Our debt-based financial system’s inadequacy in supporting businesses with intangible assets—the curse of collateral—not only slows such firms’ expansion; it also, some evidence shows, contributes to the decline in the number of startups, harming the economy. In fact, it appears to be pushing banks away from business loans into domestic property loans, which makes the banking sector more vulnerable to real-estate downturns.

All this suggests that better mechanisms to finance intangible-intensive firms would boost growth, increase opportunity, and reduce the risk of financial crises. The most important public-policy step in this context would be to equalize the tax treatment of equity and debt. Current U.S. tax policy allows firms to deduct interest payments and debt but not dividend payments to shareholders. And that means that debt finance has a lower cost of capital than equity, which intangible-intensive firms rely on more. Further, if a firm is deciding whether to invest more in intangible assets or the tangible kind, it has at present an incentive, at the margin, to go with the tangible. Tax experts have proposed ways to level the playing field, including equity tax credits, though major tax reform remains extremely difficult politically, since it invariably creates winners and losers. But as the economy becomes more intangible, the economic cost of inaction mounts.

New financial products and institutions would also help. To imagine how they might emerge, consider venture capital. From the 1945 founding of American Research and Development (a forerunner of today’s VC funds) through the establishment of Draper, Gaither and Anderson in 1958 (the first significant VC-like fund structured as a limited partnership) to today’s household-name funds, VC investors willing to take significant risks and operating with long-term horizons have played a crucial role in financing innovative firms. At least some have been motivated not just by monetary returns but also by a fierce desire to back innovation for its own sake. These include university endowments, wealthy families, and—through initiatives like the Small Business Investment Companies program—governments.

Some recent examples suggest how governments can do more to expand the availability of finance for the intangible economy. Singapore has worked with commercial banks to develop a local market for intellectual-property-backed loans; the British government has combined an IP loan program with efforts to establish markets for copyrights and other intangible assets. Governments could support projects like the Boston-based nonprofit Focusing Capital on the Long Term, which tries to connect institutional investors with firms with intangible assets.

Three other types of government institutions need to adapt to the new economy: regulators, public funders of scientific research and other intangible investments, and central banks.

Regulators are struggling to adjust to the dynamics of an economy increasingly dominated by intangible-intensive firms. A primary goal of regulation is to ensure robust competition and innovation, but this poses difficulties in the intangible economy. Challengers to incumbent firms often rely on new technologies, and regulators often lack the knowledge to assess the safety or suitability of the new tech; this can mean that the challengers must take big legal risks, as Uber has done in trying to establish itself (while also hemorrhaging billions of dollars). Irish economist John Fingleton’s proposed tech-savvy “n+1” regulator would help update the rules for the digital age, helping to support innovative new firms that existing laws impede. The n+1 regulator would grant five-year licenses to such firms, allowing them into the market provisionally. The firms would have to take out liability insurance; if the private sector wasn’t willing to offer coverage, the regulator perhaps could offer it (at a price). And the regulator would work to modify the existing rules to let the new company operate over the long term. This approach already exists, to some extent, in health care, where treatments or drugs that haven’t met with regulatory approval can be used in certain circumstances. The n+1 regulator could also strive to prevent dominant intangible-intensive firms from blocking new market competitors.

Governments also can do a better job in helping to fund knowledge. This funding already goes on, of course, whether it’s giving grants for scientific research, producing data (geographical surveys, say), or commissioning or supporting creative content. If we think about the intangible economy, government funding on scientific or technological research could—potentially—generate economically beneficial spillovers. After all, a business might see more value in building a new office than investing in R&D, so society, absent the government-funded research, would be left with less knowledge. Yet for now, the study of how governments can effectively support such innovation is akin to medicine in the age of leeching. No compelling answers yet exist on how to avoid the past failures of government industrial policies—or even on how government decides in which projects to invest. Why did government intervention help in the development of the infant semiconductor industry but not in that of fifth-generation computing? A major initiative, along the lines proposed recently by economists Tyler Cowen and Patrick Collison, to study such questions in the public interest is long overdue.

Finally, governments need to think differently about how they manage the economic cycle. For the last 40 years, officials have relied on monetary policy to help ease economies out of recessions. But in an economy ever more dependent on intangible investment, monetary policy is weakening. The primary weapon of monetary policy is central banks’ ability to set short-term interest rates, lowering them to reduce borrowing costs and hence putting more money to work in the economy. But if that lowered rate is to have the desired effect, it must be significantly below the “neutral rate”—the level seen as neither stimulating nor slowing economic growth. And that neutral rate has been falling for at least three decades. Studies point to rising precautionary savings as one reason for this trend. But another factor making interest-rate cuts less effective could be the rise in risk premiums for companies—that is, while central banks are offering lower interest rates, the rates at which firms can borrow haven’t fallen by nearly as much. And this, in turn, could be due to the rising importance of intangible capital and the attendant curse of collateral. Intangibles may also have weakened the short-run link between output and inflation—the so-called Phillips curve—since intangible-intensive firms’ ability to scale up their operations more readily makes them less likely to hike prices as demand rises. Inflation rates then become harder for central banks to influence.

Many policymakers assume that the current period of low interest rates will end, after which monetary policy will resume its usefulness as a means of stimulating the economy. But if the rise of intangibles is lowering the effective rate of interest and blunting central banks’ ability to shift inflation rates, the old days may never come back. Governments seeking to juice the economy would then have to rely more on fiscal policy.

The story told here is of a seismic economic shakeup, the political and institutional consequences of which are just beginning to play out. The market pioneers of intangible capital are reshaping the world in their image. This leaves policymakers with a choice: ignoring or resisting the changes, an approach that will ultimately render us poorer; or building the institutions and enacting the policies that will maximize the economic potential of those changes and generate greater prosperity. The right choice, challenging as it may be, is evident.

Top Photo: Mondragon Corporation in the Basque Country is a cooperative that invests heavily in technical training and R&D, running its own schools and worker-development centers. (ALVARO BARRIENTOS/AP PHOTO)