In 1822, pioneers in western Indiana named their new community in honor of General Richard Montgomery, who was killed leading Continental Army troops in the December 1775 attack on Quebec. Two centuries later, the people of Montgomery County are still thinking about the Revolution.

On a warm evening last September, several dozen residents gathered in Crawfordsville’s Carnegie Library to discuss the Declaration of Independence and how their community might mark the document’s 250th anniversary. Though the participants’ political leanings differed, the conversations were civil and productive; they found common ground in celebrating America’s founding ideals and the ongoing work of realizing them.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

The Montgomery County meeting represents the kind of grassroots organization that may take the lead in America’s semiquincentennial celebrations, a fittingly democratic approach. But large-scale events, national in scope, are in the works as well.

Planning to mark the 250th formally commenced in 2016, when Congress established the U.S. Semiquincentennial Commission, now known as America250. Chaired by Rosie Rios, former U.S. treasurer under President Barack Obama, the commission includes members of Congress, cabinet secretaries, and private citizens. Though initially intended to run on private funding, the project has since received federal support, including $150 million in the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, signed by President Donald Trump on July 4, 2025. In January 2025, the president also created a separate entity, Task Force 250. Trump has revived his proposal for a “Garden of American Heroes”—a collection of life-size statues honoring notable Americans from a diverse list of candidates. These include George Washington Carver, Calvin Coolidge, Miles Davis, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, and John Wayne. As yet, neither a location nor an artist has been selected for the garden.

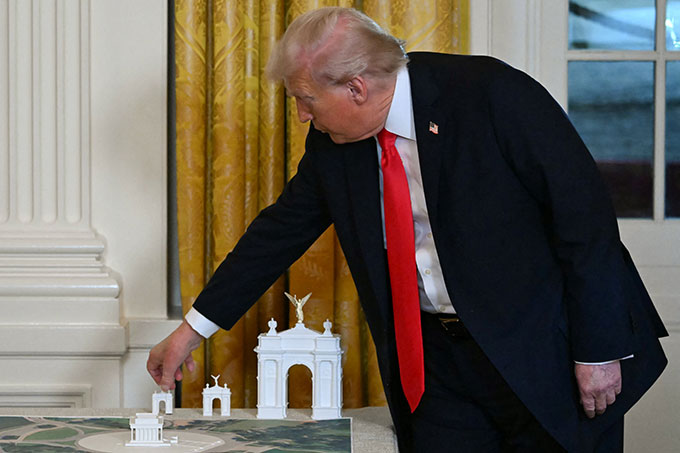

In keeping with his administration’s intention to revive neoclassical architecture among federal buildings in the capital, Trump has also proposed the creation of an “Independence Arch.” A sketch of the arch, prepared by Harrison Design, posted by Trump and seen in a 3-D model on the Resolute Desk, is inspired by Paris’s Arc de Triomphe and the Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Arch in Brooklyn. The White House has suggested Memorial Island, a traffic circle between the Lincoln Memorial and Arlington National Cemetery, as a potential location.

Some of America250’s other plans are less monumental. These include an Emerging Liberty dime and redesigned quarters depicting milestone events from the Mayflower Compact to the Gettysburg Address, “The Great American State Fair”—a traveling exhibit visiting state fairs nationwide—and “Patriot Games,” a high school athletic competition set for the National Mall next Independence Day. The commission’s 2019 report, “Inspiring the American Spirit,” also emphasized decentralization—encouraging states and localities to create their own celebrations. Many states have taken Washington up on the offer, forming their own 250 commissions, which function as a conduit for funding—coming from the federal government and flowing to local partners, ranging from historical societies and museums to civic organizations such as the Daughters and Sons of the Revolution, Freemason lodges, and others, encouraging history-based education and promoting regional tourism.

States most directly connected to the Revolution—including Pennsylvania, Virginia, and New Jersey—began their planning earliest. Pennsylvania will distribute fiberglass Liberty Bells and saplings descended from the original Liberty Tree. Virginia will offer passport books that visitors can stamp at historic sites like Mount Vernon and Monticello for prizes. Massachusetts has already reenacted the battle on Lexington Green and the Boston Tea Party; beginning in January, it will re-create Henry Knox’s artillery transport from Fort Ticonderoga to Boston.

States without Revolutionary sites are finding their own connections to America’s story. Oklahoma is celebrating Route 66’s centennial. Wyoming’s programs feature cowboy poetry and community potlucks. In Indiana, a torch of liberty (featured on its flag) will be relayed through each of the Hoosier State’s 92 counties. Ohio, where Continental Army veterans founded Marietta in 1788, is cataloging Revolutionary graves statewide, while also promoting its film-industry heritage.

Numerous cities are also planning celebrations and activities. In Boston, an archaeology project is conducting research on the city’s inhabitations during the war for independence. Sail4th 250 will bring a flotilla of tall ships to New York’s harbor and fly the Blue Angels in the sky above it. Philadelphia is hosting a series of TED talks on the future of democracy.

As the anniversary approaches, challenges remain. Many state and federal programs appear incomplete. Budget cuts and funding restraints could limit the scope of programming. More significantly, the nation’s political polarization threatens to undermine celebrations meant to unite. Americans disagree over how to interpret the country’s two and a half centuries—which stories to tell, which figures to honor.

That’s what made the Montgomery County gathering noteworthy. Attendees didn’t pretend that disagreements didn’t exist, but they found agreement in the Declaration’s ideals and in honoring not only Revolutionary veterans who settled in their county but also other Americans who worked to carry on the Founders’ work, from abolitionists to suffragists to civil rights leaders. It was a small sample, admittedly, but suggestive of possibility.

The semiquincentennial offers Americans a rare opportunity to rally around their founding document. Two hundred and fifty years after independence, the question is whether we’ll take it.

Top Photo by DOMINIC GWINN/Middle East Images/AFP via Getty Images