Rear Window: The Making of a Hitchcock Masterpiece in the Hollywood Golden Age, by Jennifer O’Callaghan (Citadel, 272 pp., $29)

Nearly a half century after his death, Alfred Hitchcock remains, despite his prolific early career in Britain, one of the most popular and scrutinized of all American filmmakers. Every 18 months, it seems, Hitchcock inspires new publications, ranging from monographs to biographies to compendiums—even a recent coffee table book about his storyboarding techniques.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

In the last three months alone, Hitchcock studies have expanded. Stephen Rebello released Criss-Cross, an engaging appreciation of his thriller Strangers on a Train. Now Canadian entertainment reporter Jennifer O’Callaghan revisits the “Master of Suspense” in Rear Window: The Making of a Hitchcock Masterpiece in the Hollywood Golden Age.

Not exactly a neglected classic, Rear Window has spawned at least three previous books and was, for years, a staple in film schools across the country, partly because of its formalism and partly because of its self-reflexive subtext. It is a film about films, specifically the process of watching films: the viewer as voyeur.

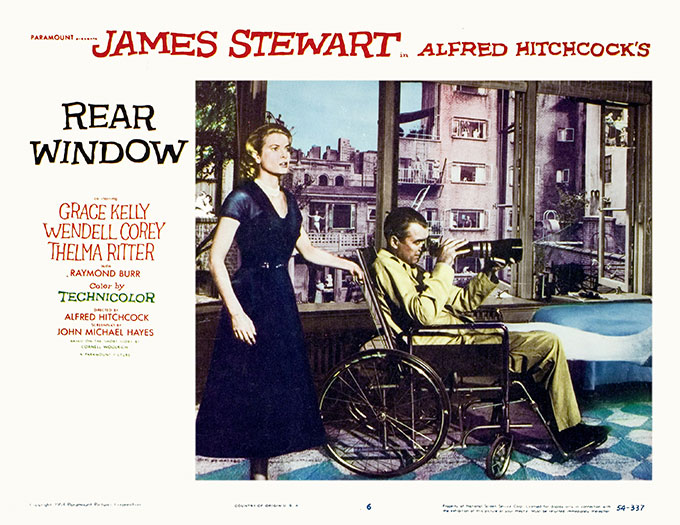

Released in the summer of 1954 to general acclaim and impressive box-office receipts, Rear Window endures as a genuine pop-art achievement, its big-budget Hollywood approach—glamourous stars, enviable costume design, blazing Technicolor, and studio-system craftsmanship—enlivened by a restless intelligence behind the camera. By mixing suspense, comedy, romance, and mystery, Hitchcock delivered a rousing if incongruous tour de force, its lighthearted tone occasionally contrasting wildly with its sordid subject. After all, if any film featuring (off-screen) murder and dismemberment can be considered lighthearted, Rear Window would be it. With a witty screenplay, an appealing star with longstanding box-office prowess (Jimmy Stewart), a promising young actress of striking, almost numinous beauty (Grace Kelly), and a talented supporting cast (including Raymond Burr as the villain and the irrepressible Thelma Ritter), Rear Window offers new delights with every viewing.

Indeed, Rear Window is so slick, charming, and apparently effortless that it seems difficult to imagine Hitchcock subsequently producing a slew of downcast films, including the bleak, Kafkaesque The Wrong Man and, especially, in 1958, the baroque fever dream of Vertigo, whose tragic ending remains both implausible and shocking.

Unlike Vertigo, Rear Window avoids mystifying the viewer. Its simple plot might have been a synopsis of a half-hour Alfred Hitchcock Presents television episode. After suffering a broken leg while on assignment, photographer L. B. Jefferies convalesces at his apartment, where, with the help of binoculars, he begins spying on his neighbors across the courtyard, eventually suspecting one of them (Lars Thorwald) of murder. Confined to a wheelchair, Jefferies enlists the aid of his undervalued girlfriend, Lisa Fremont (Kelly), to unravel the mystery.

A cynical, restless adrenaline junkie who has no interest in settling down to married life, Jefferies immediately challenges audience identification: Can a surly hero, even one played by the avuncular everyman Jimmy Stewart, arouse collective sympathy? According to O’Callaghan, the character of Jefferies is partly based on the audacious war photojournalist Robert Capa, whose fame was such in the 1940s that he had an affair with Ingrid Bergman but wound up spurning her in favor of another combat zone—a choice that reportedly left Hitchcock bewildered. How could anyone prefer hand grenades to Bergman?

As Lisa Fremont, a high-society model reportedly inspired by Anita Colby, Kelly, whose elegance far outstripped her screen accomplishments—she abandoned Hollywood less than six years after arriving—is a magnetic presence on-screen. Though Lisa wants to marry Jefferies, she also wants to refine him, imposing her own upscale values on his earthy character. As the film progresses, she eventually proves herself at his own rugged level. Two mysteries await solution in Rear Window: that of the possibly murderous Thorwald (Burr) and that of the uncertain romance between Jefferies and Lisa. These parallel storylines supply the thematic subtext that gives the film more tension than the average thriller.

Written in what some might consider a breezy style, Rear Window: The Making of a Hitchcock Masterpiece in the Hollywood Golden Age suffers from superficiality (the lack of a bibliography is telling) and, especially, from its trite language and seemingly endless clichés. We are told that, when Hitchcock received the treatment for Rear Window, “he went ape for the story,” and that Stewart and Kelly “got on like a house on fire.” Throughout its 250 pages, O’Callaghan demonstrates an almost sadistic pleasure in flogging the reader with stock phrases and platitudes. On those who doubted Rear Window as a potential box-office hit: “As is standard practice, whenever an artist dares to venture off the beaten path, naysayers crawl out of the woodwork.”

O’Callaghan’s book offers no new revelations, no provocative analysis, no critical viewpoint—just a dutiful adherence to what has been repeated on content farms and entertainment sites such as Collider or Indiewire. Without an interpretive framework, the book suffers from blandness, as well as a sensibility that never seems fully engaged by its subject.

O’Callaghan dutifully recounts the film’s production history—from its adaptation from a Cornell Woolrich story to casting and shooting—with an early emphasis on the technical aspects of the sprawling set. Hitchcock had a fondness for gimmicks—the Salvador Dalí dream sequence in Spellbound, the ten-minute-takes and single set of Rope, the 3-D hijinks of Dial M for Murder—and, with Rear Window, he introduced his cleverest gimmick of all. Though Rear Window was his third film with a restricted setting (after Lifeboat and Rope), Hitchcock seemed to relish the scale of the challenge this time around. Rear Window takes place entirely in a single room: where Jefferies watches the action across the courtyard (first with binoculars, then with a camera/telephoto lens combination), forcing the audience to share his subjective point of view. To realize his bravura vision, Hitchcock had one of the most elaborate sets since the days of Cecil B. DeMille constructed. At a cost of “$9,000 to design and $72,000 to build,” Paramount erected a life-size model of a Greenwich Village apartment complex.

In describing the challenges of shooting synchronized scenes in each of the apartments, O’Callaghan is straightforward, allowing the amazing technical details to emerge from a welter of information. “Each of the apartment complexes had running water, electricity, and support from steel girders, so they could technically be lived in,” writes O’Callaghan. “Since they were fully functioning, Georgine Darcy [who plays nubile young dancer Miss Torso] claimed to have essentially lived in her small apartment and never left the studio during most of her time working on Rear Window.”

Elsewhere, O’Callaghan skims through the soundtrack (by the prolific Franz Waxman), sprints past the backstories of Kelly, Stewart, and Edith Head, and sails over skirmishes with the Production Code Authority. Then, after roughly 120 pages, Rear Window disappears. The second half of the book chronicles, with increasing digressions, the film’s cultural legacy and the afterlives of its participants. Subsequent sketches of the supporting cast and several peripheral figures (including Monaco’s Prince Rainier III, widower of Kelly) and subjects (what Stewart thought of Dustin Hoffman in The Graduate) give Rear Window: The Making of a Hitchcock Masterpiece in the Hollywood Golden Age a disjointed air. But the film’s production details and accomplished personnel are intrinsically fascinating enough to rise above the gossipy tone and routine conclusions.

Despite its fairly mundane treatment here, Rear Window remains, from any point of view, an exemplary, exhilarating entertainment in the Hollywood grand manner.

Top Photo: Grace Kelly and Jimmy Stewart in Rear Window (Photo by FilmPublicityArchive/United Archives via Getty Images)