Willis and Vivian Bramstaedt planned to live out their days on a farm in rural Beecher, Illinois. But two years ago, they got a disturbing letter from the Illinois Department of Transportation: the state, using its eminent-domain powers, would seize their land to provide space for a brand-new airport—intended to relieve congestion at Chicago’s O’Hare International Airport, some 60 miles north. Critics of the proposed new airport note that O’Hare is expanding, nationwide air traffic is flat, and Illinois is almost broke. Nonetheless, the state has spent about $33 million gobbling up land for the new airport, even though the project has yet to win approval from the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). The Bramstaedts have become resigned to losing their farm, they told the Chicago Tribune.

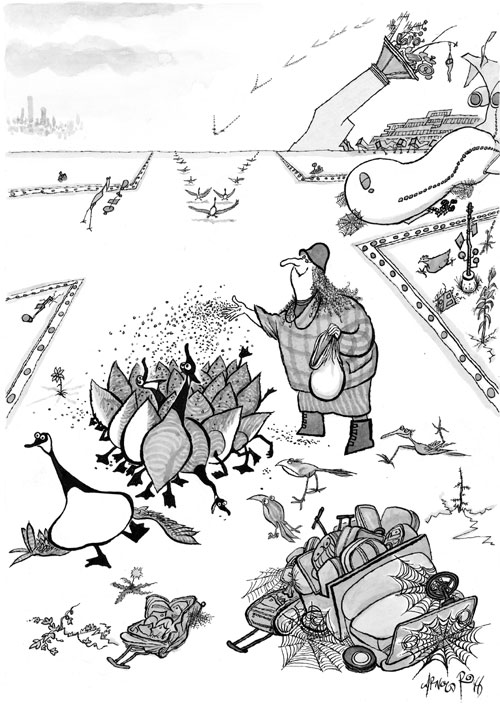

If the Illinois project goes forward, it could join a growing list of new or expanded airports that are severely underused and, in some cases, virtually empty. Despite a bleak decade for air travel—the result of the 9/11 terrorist attacks and the post-2008 economic downturn—local governments, aided by Washington, have been pouring billions of dollars into airport development and expansion. They claim that these expensive, debt-laden facilities will spur growth in economically precarious locales by attracting businesses that want more air connections. But from St. Louis to the Florida Panhandle, this Field of Dreams approach—build it, and they will come—hasn’t worked. And taxpayers have been stuck with the bill.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

In 1978, Washington unleashed vast changes in America’s airline industry, deregulating fares, routes, and the entry of new competitors, which federal oversight had long restricted. A host of low-cost carriers arrived on the scene, and some of the established airlines, now free to enter new markets, moved toward a hub model, in which passengers fly to a central airport and transfer to connecting flights. Deregulation also sent fares plummeting. Today, the average plane ticket is 30 percent to 40 percent cheaper than it was in the regulated era, adjusted for inflation. Business soared, with passenger volume increasing from about 270 million passengers annually in the late 1970s to about 730 million last year. Employment in the industry exploded—up 35 percent, to about 450,000 people.

Most of the growth caused by deregulation occurred before 2001, however. Over the troubled 2000s, airline employment declined, and passenger traffic rose only slightly—growing just 0.2 percent per year from 2000 through 2010, compared with about 4.6 percent annually in the 1980s and 1990s. The harsh business climate forced many big airlines to shrink, merge, or go bankrupt, and they began abandoning unprofitable routes and airports that didn’t generate sufficient revenue. Because airports rely heavily on the fees that airlines pay them, which vary according to use, the shift hit them hard, especially those that already owed a lot of money to pay off their construction or expansion. And airports that had expanded to accommodate hub traffic saw unprecedented declines in business, since they generated most of it from passengers taking connecting flights, which airlines suddenly eliminated or shifted elsewhere. Airports that relied on local business lost far less traffic.

One of the big losers was Pittsburgh International Airport. In the immediate years after deregulation, it had become a key market for USAir, then one of the nation’s most profitable carriers. Local leaders, using USAir’s success as a justification for expanding and upgrading the airport, began urging the airline to finance a new terminal. According to a retrospective account in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette by former USAir chairman Edwin Colodny, airline executives initially balked, arguing that it would be less expensive to expand the airport’s existing terminal. By the late 1980s, though, USAir had reluctantly committed to occupy a new $1 billion terminal, which would be built with local-government debt. To help service that debt, USAir would henceforth pay Pittsburgh International dramatically higher fees—as much as $50 million a year, compared with $10 million before. The airline moved into the new terminal in 1992, and by 1997, Pittsburgh International was handling nearly 21 million passengers a year, most of them flying USAir. But only 20 percent of those passengers originated in Pittsburgh; the rest were transfers.

Then came the 2001 recession and the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Business slumped, and new, low-cost carriers began competing for USAir’s passengers. The reeling company entered bankruptcy in 2002, exited in 2003, and then reentered in 2005. It sought to reduce its fees at Pittsburgh International, saying that it was losing tens of millions of dollars a year, but the airport resisted. So USAir began scaling back, shifting transfer flights to less expensive locations and laying off thousands of Pittsburgh-area workers. USAir currently operates only a few dozen flights from Pittsburgh, down from a peak of nearly 550, and the airport’s total passenger volume has dropped to about 8 million a year—far fewer than the 32 million once predicted by local leaders.

USAir’s diminished role left Pittsburgh International with a $25 million budget gap for annual debt-service payments for the new terminal. The airport filled the hole with taxes on passengers’ tickets and with $10 million a year in proceeds from legalized gambling, which Pennsylvania is now funneling into the airport. Pittsburgh International still owes some $450 million for the terminal. To save money, officials have also shrunk the airport that cost so much to expand. Of the nearly 100 gates in use at the height of Pittsburgh International’s traffic, only half are active today. One concourse in the 1992 terminal has been demolished, and whole sections of two others, occupying nearly 100,000 square feet, have been closed indefinitely.

Some hubs have invested hundreds of millions of dollars to retool even after they’ve lost traffic. A good example is Lambert–St. Louis International, which emerged as a major airport after TWA made it a hub in 1982. Traffic expanded steadily during that decade, but TWA ran into financial woes, going bankrupt in 1992 and then again in 1995. Nevertheless, in 1998, Lambert executives began urging the FAA to let them undertake a massive expansion, which eventually cost $1.1 billion. In 2001, TWA, still financially shaky, merged with American Airlines, which began winding down the St. Louis hub. Passenger traffic evaporated. But Lambert officials pressed ahead with the expansion anyway, predicting that the airport would reemerge as a big hub.

To engineer the expansion, which involved building a third runway, the airport used eminent domain to seize 79 businesses and approximately 2,000 homes in Bridgeton, a nearby community. Despite protests that the runway was unnecessary—daily takeoffs and landings were down significantly—the airport had razed about 1,500 of those homes by 2005. Local residents dubbed the giant project “airpork” because it created temporary construction jobs but little permanent growth. By some estimates, the airport uses the new runway—which Washington helped finance with $165 million in federal funds—less than 10 percent of the time. Annual passenger traffic is down from a peak of 30 million in 2000 to 12 million today. As a former resident summed up the debacle: “Six thousand people lost their homes for nothing.”

Expanding airports isn’t always a bad idea, of course. In a growing, thriving region, it may make sense: Atlanta’s Hartsfield-Jackson, for example, has spent $6 billion over the last decade to add needed terminal space and parking. Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport is investing $2 billion in new space to meet rising demand.

But it’s misguided to think that airport expansion itself will lure businesses to a region by offering them more flights. In fact, airport expansions often increase ticket prices, driving businesses away. After airports have built new facilities, they pass the expense on to passengers in the form of pricier tickets. If an airport has expanded to become a hub, moreover, passengers there may have to pay the “hub premium” that a dominant airline at a location often levies to make up for losses at other facilities.

You can see those extra charges reflected in the sky-high fares at Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky International Airport, a Delta hub and winner of the top spot in Forbes’s 2009 list of “rip-off airports.” Last year, an average ticket out of the airport cost $526, compared with $372 in nearby Dayton, Ohio, and $387 in Indianapolis. International flights averaged $1,408, 36 percent more than the national average. Is the airport really a reason to relocate to the area, as businesses often claim? The Cincinnati Business Courier found that three-quarters of the Cincinnati firms it surveyed were flying employees out of the Dayton airport, more than an hour away by car. “Unless you’re suffering from delusion, you realize that the Cincinnati airport is now really in Dayton,” aviation expert Darryl Jenkins told the Cincinnati Enquirer. Similarly, a 2006 study found that nearly one-fifth of local fliers drove to other airports to avoid the hub’s high prices. Delta is now reducing flights from Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky, and passenger traffic at the airport is down 65 percent since 2005.

Local governments and Washington have gone still further, creating brand-new airports and betting that business for them will materialize. An early example was the $300 million that Illinois officials and the federal government spent in the nineties to build MidAmerica Airport in largely rural St. Clair County, 40 miles east of St. Louis. Like the Lambert officials, MidAmerica’s backers assumed that TWA, which had already gone bankrupt once, would keep expanding in St. Louis, elbowing out other carriers and creating the need for a new airport. Illinois officials projected that the new facility would be handling 2.5 million passengers a year by 2005. The FAA contributed $220 million, much of it for land acquisition, and St. Clair County came up with another $70 million, raised through debt.

MidAmerica opened in 1998, when national air traffic was still growing robustly, but it had no airlines providing regularly scheduled flights; indeed, the airport was virtually empty, except for charter flights. It took MidAmerica two and a half years to land its first scheduled passenger service, by Pan American Airways, the second reincarnation of the once-giant airline. That service started in August 2000 and ended in December 2001, a casualty of lackluster sales. Three other airlines—Great Plains, TransMeridian, and Allegiant—tried to make a go of MidAmerica, only to pull out quickly, even though they had received financial assistance to operate there. Great Plains went bankrupt in 2004, still owing St. Clair County, which runs MidAmerica, $750,000 in loans.

After several failures to attract passengers to MidAmerica, county officials then tried to create a cargo business at the airport. The county spent nearly $6 million on refrigeration equipment and on subsidizing charter flights of flowers imported into the United States from South America, but the business never took off. Undeterred, the county proceeded to pay a New York entrepreneur $250,000 to build a new warehouse at MidAmerica for his prospective business of hauling Chinese cargo into the country. The businessman proved unable to find any private investors to back his venture, which fizzled. The county has yet to get its $250,000 back.

Last year, MidAmerica officials induced a Michigan company to build a refrigerated warehouse on airport grounds. The county is investing $2.5 million in the venture, which will employ up to 80 people, officials hope. But with no service to boast of, the airport continues losing money—about $12 million a year. Losses over 14 years now top $150 million. That dismal record recently prompted a local newspaper to say that perhaps the time had come to close the airport. Two problems with that option: St. Clair County has piled up $134 million in debt on the airport, and it would also have to return millions of dollars’ worth of land-acquisition grants to the FAA.

The MidAmerica debacle should make Illinois officials pause before planning any new airports. Yet they keep pushing for the Beecher-area facility, just 500 miles away, that will displace the Bramstaedts. In 2004, Barack Obama, then a candidate for one of the U.S. Senate seats from Illinois, claimed that the proposed airport would create 15,000 permanent downstate jobs. Last November, Congressman Jesse Jackson, Jr., promoting the airport plan on C-SPAN, reiterated Obama’s promise of 15,000 jobs and urged Governor Pat Quinn to free up funds for more land acquisition. Advocates of the project, which Jackson has dubbed the Abraham Lincoln National Airport, predict that locals tired of O’Hare’s crowds and delays will flock to the new facility. Yet O’Hare is spending $6 billion on a massive expansion plan, and passenger traffic there has slumped by 10 million, or 15 percent, over the last seven years, apparently confirming what United Airlines CEO Jeff Smisek said earlier this year: that the region clearly didn’t need another airport.

A new airport in the Florida Panhandle may be the most striking example of the folly of the if-you-build-it-they-will-come theory. Back in 2007, Florida officials and a private developer, the St. Joe Company, sold the FAA on the idea that constructing an international airport in sparsely populated Panama City (population: 37,000) would pay off by igniting rapid regional development. St. Joe, the largest landowner in northwestern Florida, donated 4,000 acres of the nearly 82,000 it owned in the area for the facility. In a nonbinding referendum, local residents voted decisively against a new airport, but Florida officials and the FAA proceeded anyway. The state kicked in about $110 million, the FAA added $72 million, and the county picked up the tab for much of the rest.

So Northwest Florida Beaches International Airport opened in 2010 at a cost of $300 million, the first major addition to America’s stock of airports since September 11. St. Joe got ready for the anticipated gold rush, announcing plans to build nearly 6,000 custom homes and 4.4 million square feet of commercial space on 80 acres surrounding the airport. But the gold rush failed to arrive, to put it mildly. Northwest Florida Beaches opened during a national housing bust, which sent home prices spiraling downward nearly 50 percent in Florida and resulted in nearly 500,000 foreclosures in the state in 2010. Disgruntled investors ousted St. Joe’s management and wrote down the value of the company’s real estate, including holdings around the airport, by 80 percent, or $375 million. Wall Street investor David Einhorn, who bet against St. Joe’s shares, charged that the company consisted of little more than a series of “ghost towns” and that the airport presented little opportunity for growth.

This past January, St. Joe’s announced that it was “putting an end to the ‘build it and they will come’ ” real-estate strategy, the Panama City News Herald reported. Southwest Airlines is currently operating at Northwest Florida Beaches, drawn to the airport by St. Joe’s willingness to offset any losses that it may incur. But the resulting air traffic hasn’t been remotely sufficient to transform the area.

Will the Aerotropolis Fly?

From St. Louis to Detroit to Memphis to Denver, the idea of the “aerotropolis” has become increasingly fashionable. As John Kasarda, a professor at the University of North Carolina’s business school, defines it, the futuristic term describes a city that has grown around an airport, providing residents and businesses with super-quick access to global networks of commerce and travel. Some of these cities, Kasarda imagines, will be built from the ground up. A striking example is South Korea’s New Songdo, currently rising on a man-made island in the Yellow Sea and connected by bridge to one of the world’s busiest airports, Incheon International. But existing cities, Kasarda suggests, could also evolve over time into aerotropolises.

Enamored with Kasarda’s idea, cities that have seen their air traffic vanish are trying to lure it back by promoting themselves as the first American aerotropolises. The concept is a tough sell, though. Trying to make up for the loss of 60 percent of its passenger traffic, Lambert–St. Louis International Airport has tried to turn itself into a cargo hub centered on trade with China, hoping to generate a wave of development. Lambert officials have had numerous meetings with Chinese investors, who are seeking significant government incentives, including $360 million in tax breaks, to build new warehouses around the airport. These demands have helped stall the plan, with budget-crunched legislators hesitating to award fat incentives to businesses at a time when they’re slashing services to residents. Critics note, too, that Lambert already spent $1 billion on a previous expansion intended to secure the airport’s prominence as a passenger hub—a move that failed. And as two University of Missouri professors pointed out in a newspaper op-ed: “If the Aerotropolis won’t fly without public subsidies, that means private venture capitalists think the project is a loser and won’t risk their money.”

If there’s any city whose airport might seem likely to spawn a surrounding aerotropolis, it’s Memphis, home of Federal Express, which has turned the city’s airport into the second-largest cargo hub in the world. Hoping to capitalize on that relationship at a time when Delta has cut some 25 percent of its passenger flights at Memphis International Airport, city leaders have rolled out the slogan “Memphis: America’s Aerotropolis” and are marketing the area to businesses looking for a location that allows them to plug in to global networks.

But Memphis’s experience illustrates a problem with the viability of the aerotropolis idea: many businesses don’t want to locate in industrialized airport settings—which tend to be ugly and lacking urban amenities—just for the sake of easy airport access. Even FedEx, which employs thousands of cargo handlers at the airport, has been moving its front-office employees to suburban office developments, leaving behind hundreds of thousands of square feet of unused space. The office district around Memphis International Airport now has the highest vacancy rate in the city, north of 50 percent. A stark symbol of the area’s struggles is a four-story office building named Aerotropolis Center, which has been vacant for five years.

Denver International Airport may have a better shot at giving rise to an aerotropolis. Opened in 1995, the airport is surrounded by miles of undeveloped land. One 1,287-acre site adjoining the airport has already been slated for retail, hotel, and office space. But the development is possible only because the airport is 30 miles from downtown Denver, in the city of Aurora, where there’s plenty of room to expand, far more than in the congested urban settings of many current major airports. That kind of free space may be the key, at least in the short term, to creating an American airport city.

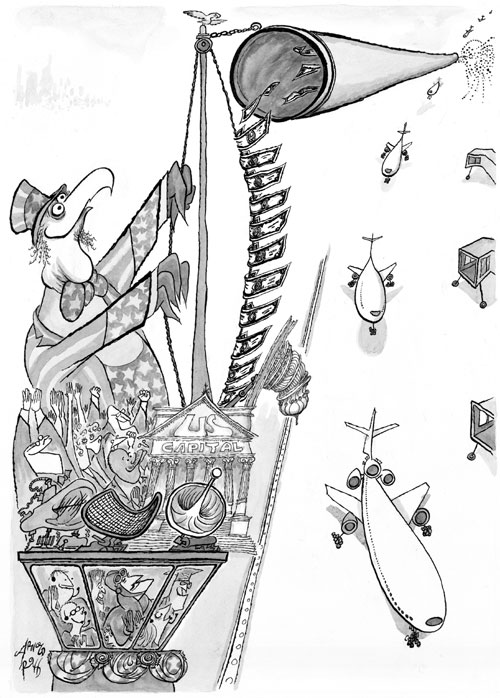

For decades, the federal government has also spent tens of millions of dollars yearly to subsidize airports in smaller communities, arguing that their economies depend on connecting directly with the American air-travel system. The practice began in 1978 as a transitional $7 million yearly subsidy for these airports as the country moved to a deregulated system. It has since swelled into the Essential Air Service program, which extends $200 million a year in grants to small airports to pay airlines to continue service when it isn’t profitable. Today, some 34 years after deregulation, 122 community airports receive the subsidies.

Last spring, investigative reporters for Scripps Howard News Service boarded 11 flights at subsidized airports and found just two of them carrying more than two passengers. Together, the 11 flights had 130 empty seats, for which taxpayers nevertheless paid a total of $155,000. On one flight between Baltimore and Hagerstown, Maryland—just 70 miles apart—the captain invited the one passenger who wasn’t a reporter to sit in the copilot’s seat. On a 300-mile flight between Las Vegas and Ely, Nevada, there were no passengers at all, other than the reporter. The federal government subsidized that route to the tune of $3,700 per passenger.

Defenders of the program, like the advocacy group Rural Air Service Alliance, call these airports “economic drivers.” But if that were the case, the economic activity generated by the subsidies would have made many of the facilities self-sustaining after all this time. The best that Congress could do earlier this year—in an era of massive federal deficits—was modify the program by dropping two airports, including the one in Ely, from the list of subsidies and saving a grand total of $3 million.

Public officials and local business leaders in areas looking to stimulate growth argue that they need to invest in airports, just as Atlanta and Dallas have. These officials are willing to risk millions of taxpayer dollars on a bet that it’s an airport that drives a local economy, not an energized economy that drives airport expansion. The results are empty terminals and gates, unused runways, and even flight-free airports. In China, the government has swiftly constructed entire new cities that so far remain eerily without residents. America is building a network of ghost airports every bit as strange.