Bill de Blasio leaves the mayor’s office with an ambivalent legacy on homelessness. As the New York Times recently pointed out, family homelessness is now about 30 percent lower than when de Blasio was inaugurated, but single adult homelessness is up by about two-thirds. Total homelessness is down—but before de Blasio takes a victory lap, it should be noted that homelessness has gone down, briefly, under every mayor since Ed Koch. A new mayoral administration creates the opportunity for a reset on homelessness policy.

The trend in New York has been ever-rising homelessness, punctuated by temporary lulls and reductions. Between spring 1987 and summer 1990, the shelter census dipped 37 percent. That didn’t last. And even as overall numbers have declined in recent years, the average length of stay in shelter has continued to rise to more than 500 days for single adults and families with children alike. That indicates, as if reports from the subway were not evidence enough, that city government still has many hard cases on its hands that it doesn’t quite know how to handle.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

New York’s new mayor Eric Adams should begin with oversight, to address the wave of corruption that swept homeless services during the de Blasio years. Late in November, New York attorney general Letitia James announced that Ethel Denise Perry, the former head of shelter operator Millennium Care, had pled guilty to tax evasion and grand larceny charges. Perry stole more than $2 million intended for her homeless clients and used it on various personal expenses, including shopping excursions to Tiffany’s and Bergdorf Goodman. Also in late November, the city announced plans to shut down shelters run by the CORE Services Group. This decision came following reporting by the New York Times and New York Post about excessive executive compensation, the directing of subcontracts to firms in which CORE Services Group’s leadership had a vested interest, and leaders’ past involvement in other government-contracting scandals.

Overindulgence by the city and shady subcontracting were also central to the Victor Rivera saga. Rivera, the former head of a large shelter provider, the Bronx Parents Housing Network, was charged over an alleged kickback and bribery scheme back in March 2021. The month before, public reports surfaced of Rivera’s sexual harassment of a number of staff and shelter clients, two of whom “were given payments by his organization that ensured their silence,” according to the New York Times. Scandal followed Rivera’s reputation for years before action was taken against him.

Other homeless-services groups that have faced serious corruption allegations include the Bushwick Economic Development Corporation, Childrens Community Services, Acacia Network, and Aguila, Inc. A recent New York Post analysis estimated that, under de Blasio, more than $4 billion had flowed to homeless service providers “with questionable records.”

In recent years, city officials responded to homelessness with a crisis mentality that prioritized getting as much money out the door as quickly as possible and viewed scrutiny as a luxury. New York’s “Right to Shelter” law imposes, as de Blasio portrayed it, an honorable but awesome duty that can only be fulfilled via tragic compromises. When pressed on Inside City Hall to explain why New York knowingly did business with ethically suspect providers, de Blasio said: “We have a Right To Shelter law, which is the right thing in this city. . . . But it comes with a huge obligation to provide services. And there’s only so many organizations willing to do it.”

But the recent decline in homelessness should mean that complying with the Right to Shelter has become less onerous, giving the city less of an excuse for letting oversight slide. Mayor Adams should apply increased scrutiny to shelter operators, beyond just making sure that they’re not stealing.

New Yorkers need a clearer idea of how well the hundreds of local shelters are serving the homeless. Mayor Michael Bloomberg ran a benchmarking program that rewarded shelters based on how efficiently they moved clients into permanent housing. The New York City Independent Budget Office has estimated that reinstating the Bloomberg program could save the city about $20 million annually.

De Blasio never explained why, exactly, he found it so unrealistic to replace dubious contractors with more promising ones. Adams should couple a new oversight regime with efforts to encourage more responsible innovation in homeless service delivery. Homelessness hasn’t seen such innovation in a while. The funding has tended to flow to massive conglomerates such as Project Renewal and CAMBA. Even when not leading to scandal, this tendency violates the spirit of creativity that’s supposed to animate the nonprofit-contracting model.

Another neglected priority in homeless services is employment. While the city will sometimes tout the employability of its homeless clients in an effort to promote a down-on-their-luck idea of homelessness, true work-oriented programs could use more support than they’ve enjoyed. Amid a historic expansion in homeless funding, transitional housing units in New York have declined by about 40 percent since 2014. Thanks to the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s doctrinaire embrace of the so-called Housing First philosophy, renowned work-oriented programs, such as the Doe Fund, have experienced federal funding cuts. But as the retail, restaurants and hospitality, transportation, and construction industries face labor shortages, jobs can offer some homeless adults a foothold in the working class.

For the vast majority of the non-chronically homeless, self-sufficiency should be the goal. The city should ask homeless-service providers for ideas about how to take advantage of the labor shortage. If pressure to find temporary housing for everyone who needs it has eased, then attention should turn to employment.

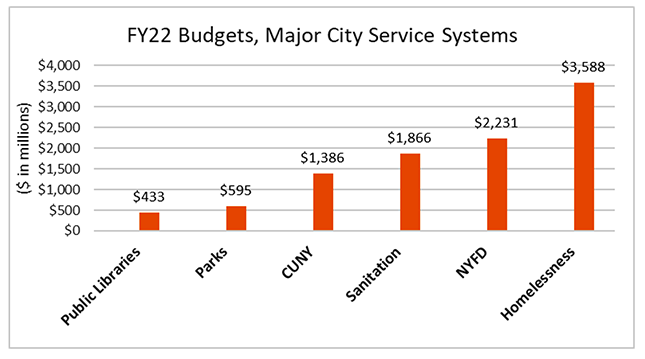

Lastly, the Adams administration should revisit the question of whether New York really needs a standalone Department of Homeless Services (DHS). Currently, the DHS oversees most city shelters, under a plan proposed in the early 1990s by a commission appointed by Mayor David Dinkins and headed up by Andrew Cuomo. Back then, many believed establishing a dedicated city department for homelessness would demonstrate a serious commitment. But New York no longer needs to prove that it cares for the homeless. At $3.6 billion per year—much of it not handled by the DHS— homeless services stands as one of the largest municipal systems that the city runs:

What might an alternative model entail? Former city council speaker and shelter operator Christine Quinn voiced support for folding the DHS into the larger social services bureaucracy. Mental illness, disability, addiction, family instability, unemployment: these problems have a concreteness that housing instability lacks. Helping people fix the problems in their lives sometimes requires temporary housing resources, but there’s a difference between conceiving of housing stability as means to a larger end and conceiving of it as an end in itself. Taking the resources now controlled by the DHS and distributing them among other departments would affirm that housing stability is a necessary but insufficient goal in helping people lead better lives.

New York still has more homeless people than any other U.S. city, but that does not mean that the city is negligent toward the homeless. Adams should shift the debate away from why the city isn’t doing more to what it could do differently—and better.

Photo by Andrew Lichtenstein/Corbis via Getty Images