In March 2017, with U.S.–German tensions simmering over defense spending and trade agreements, German chancellor Angela Merkel came to the White House, looking for common ground with President Donald Trump. Perhaps fittingly, for a president who once hosted television’s The Apprentice, one fruitful area turned out to be youth apprenticeships. Aware that Trump had touted work-study programs as a promising path to well-paying jobs for those who didn’t want to go to college, Merkel brought along key German industry leaders. Together with White House officials and American business executives, they discussed the well-developed German apprenticeship model, which has helped make Germany’s youth-unemployment rate one of Europe’s lowest.

One of the German executives in attendance, Siemens CEO Joe Kaeser, noted that his firm—with 50,000 U.S. employees—had brought the German system to America years ago, to help staff its technically sophisticated manufacturing plants. “A highly skilled manufacturing workforce is critical to Siemens in the United States,” Kaeser said, emphasizing how “industry, academia, and government can work together to help empower workers with the skills needed for success in today’s advanced manufacturing environment.” “That’s a name I like, ‘apprentice,’ ” the president responded, thanking Siemens and other German firms for their work in the U.S.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Many apprentice-model advocates point, though, to an American educational disconnect. On the one hand, young men and women uninterested in attending a four-year college find it increasingly tough to land good jobs in industries that have grown steadily more technical and specialized. On the other hand, many companies in such industries complain that they can’t find enough workers to staff their expanding businesses. A big part of the problem, many agree, is that, over the last half-century, American schools have de-emphasized career and technical training in favor of a college-for-all agenda that hasn’t served the interests of many students.

Recognizing the problem, some firms operating in America are forging ties with local educators to start youth apprenticeships. Among the most successful are European-based firms—especially German, Swiss, and Austrian. The initiatives they’ve launched offer a model for what the U.S. should do more extensively. To build them, companies had to overcome skepticism from school systems and the persistent belief among parents that college is necessary for their kids’ future. “It will be impossible to build a twenty-first-century workforce if the talent pool is half-full or if the only way to participate is to have a Ph.D. or college degree,” said Barbara Humpton, CEO of Siemens USA, at a company-sponsored conference last year.

Apprenticeships date from the Middle Ages, when worker guilds allowed master craftsmen to employ young, inexperienced workers cheaply, in exchange for training. In America’s early years, apprenticeships provided training for orphans or impoverished children. Arriving waves of European immigrants in the nineteenth century spurred the growth of continental-style apprentice programs, in which parents made agreements with skilled artisans to train their children, in exchange for the children’s labor. In the late nineteenth century, states started enacting laws formalizing some of these agreements, and, in 1937, Congress passed the National Apprenticeship Act, which set countrywide standards for apprenticeships. But after World War II, as returning servicemen used the GI Bill to attend college and subsequently obtain professional jobs, a college degree increasingly became the educational system’s primary goal; technical training receded.

One unanticipated result has been manufacturing firms’ trouble in finding skilled workers. In 2011, with nearly 14 million people in the U.S. out of a job because of the Great Recession, the Manufacturing Institute estimated that eight out of every ten manufacturing firms were struggling to locate the right workers to hire. That represented perhaps 500,000 to 1 million unfilled jobs, on some estimates. The need has grown in recent years, as the economy rebounded. A 2018 survey calculated that the skills gap among the young left more than 2 million positions at technically sophisticated manufacturing companies unfilled. Too many American high school graduates simply aren’t ready. “There are no jobs for kids who don’t have high literacy and numeracy skills and a work ethic,” the superintendent of the Charleston County (SC) School District, Gerrita Postlewait, told a national conference on apprenticeships last year.

Something very different was transpiring in countries like Germany, Austria, and Switzerland. In 1969, at the urging of employers and trade unions, the German government passed the Vocational Training Act, setting up programs in which high school and work experience could be combined for hundreds of different occupations. Today, nearly two-thirds of German 18-year-olds—more than 500,000 youths yearly—enter into contracts with employers to work as apprentices. In Germany and Austria, about 3.7 percent of the workforce are apprentices at any given time. By contrast, in America, apprentices constitute only about 0.2 percent of all workers. “As high-wage countries, Germany and the U.S. face similar challenges in protecting existing production facilities and creating new manufacturing jobs,” Peter Wittig, the German ambassador to the U.S., wrote in the Wall Street Journal after the White House meeting. “One of the most decisive factors for companies is whether they can find skilled and motivated workers, which is what apprenticeship programs provide.”

The lack of apprenticeships in the U.S. is also an investment issue. Suzan LeVine, commissioner of the Washington State Employment Security Department, describes how, when she was the U.S. ambassador to Switzerland from 2014 through early 2017, she would pitch that country’s biggest firms to expand their U.S. operations. The sticking point was talent. “They weren’t asking for tax incentives,” she says. “They wanted talent incentives.” Switzerland, like Germany, had a comprehensive apprenticeship model that delivered workers to these companies in their domestic locations; the lack of a similar system in the U.S. made hiring there harder.

In pockets around America, however, European firms with apprenticeship traditions have been developing local work-study initiatives that open a pipeline for youth employment. Some of the most successful are in North and South Carolina, attracted by a cluster of high-tech research facilities and major American firms in places like the Raleigh-Durham research triangle and in successful cities like Charlotte and Charleston.

“Today, nearly two-thirds of German 18-year-olds—more than 500,000 youths yearly—enter into apprenticeships.”

One of the earliest efforts started in the mid-1990s, eventually becoming a partnership between Siemens, Austrian manufacturer Blum Inc., and Daetwyler USA, the American operation of a Swiss conglomerate. Together, the firms set up a work-study pipeline in North Carolina known as Apprenticeship 2000. Students follow a career path through a four-year program spanning two years of high school and then requiring courses at Central Piedmont Community College. They must complete 6,400 hours as apprentices and 1,600 hours of postsecondary class work. The companies invest heavily in the training. Blum estimates that it costs $175,000 to produce a single worker—an indication of how valuable trained employees in a manufacturing firm can be. The apprentice-training facility boasts $1.8 million in equipment. In the U.S., many still regard career and technical training as options for students lacking the smarts for four-year college—but the companies in Apprenticeship 2000 screen high school juniors extensively, requiring applicants to take math tests and maintain at least a 2.8 grade-point average. Only about 40 percent of applicants make the cut.

Early on, Siemens partnered with the Olympic Community of Schools, a group of specialized high school academies in Charlotte, to recruit candidates. To be considered, students had to take advanced high school math courses like calculus and maintain As and Bs. Applicants had to take a company test to qualify, and then do a short apprenticeship while in high school; from this group, the company chose a select number as apprentices, who’d finish an associate’s college degree while working. Those subsequently hired by Siemens could start at salaries as high as $55,000 a year, and the company would have paid for their education.

One reason for the stringent standards is the transformation of manufacturing in the industrialized world, where making everything from medical equipment to parts for increasingly computerized cars requires advanced training. Barbara Humpton says that Siemens is now one of the world’s largest software firms, with a bigger workforce than technology giants like Google, Microsoft, or Apple. Siemens, for instance, offers apprenticeships for machinists, electricians, and technicians to specialize in mechatronics, which involves electrical and mechanical systems and includes the study of robotics, telecommunications, and production systems. “In the past, a machinist would have had to learn how to use a machine. In a digital world, the machinist must also learn how to program that machine,” she says.

This evolution of the factory floor has created a new kind of job, what some refer to as middle-skill tech work—now abundant in sectors like manufacturing, energy, and health care. Siemens predicts that half of all job openings through 2022 will be in these middle-skill areas—a striking figure, considering that our high schools and many of our colleges are not equipped to produce such workers. Other employers see the same trends. A Charleston Chamber of Commerce study estimated that the greater metro region would add 35,000 new jobs in the next five years and that 80 percent will be in specialties where community college work-study programs offer an employment path.

Without national coordination, U.S.-based companies looking to create apprenticeships face the challenge of getting cooperation from local high schools, community colleges, and state labor officials, who must certify these efforts. For many firms, especially smaller ones, the task can be overwhelming. But in the most successful initiatives, intermediaries step in to help. South Carolina’s statewide apprentice program, Apprenticeship Carolina, is part of the state’s technical-college system. It employs six consultants who help businesses develop and register work-study programs. In 2008, the state had 777 apprenticeships at 90 companies; it now boasts 1,000 companies and some 30,000 registered apprentices, according to Brad Neese, vice president of economic development at the South Carolina Technical College System.

Slowly, the presence of such organized efforts, with employers visiting high schools to pitch students and parents, has begun to break down the opposition to career training. One powerful motivation is the growing perception that college has become too expensive and that many four-year college graduates are underemployed, earning far less in their first jobs out of college than they expected, even as they’ve piled up student debt. By contrast, most apprenticeship programs pick up all the costs for students and typically guarantee a job at an income level far above that of the average high school graduate—and even above what many college grads initially earn. “One of the biggest benefits,” Jordan Fancy, an apprentice with Cummins Turbo Technologies, told a gathering of educators last year, “is free college. People in four-year colleges going into the same field as I am are coming out with $40,000 in debt. I don’t have that. And I also have work experience.”

Apprenticeships also tend to have a higher rate of completion than four-year colleges, where as few as 55 percent of students earn a degree in six years. In high school career programs that don’t include work-study, moreover, as few as a third of students finish certification. By contrast, more than 60 percent of work-study students finish. “For some students, college for college’s sake isn’t a compelling argument, but when you have the employer connected, college for employment’s sake is a better outcome,” argues Tina Wirth, a vice president at the Charleston Chamber of Commerce.

The apprentice route succeeds partly because students work on-site, where they develop not just expertise but also more general skills, including basic competencies like showing up on time and other elements of the work ethic that often go untaught elsewhere. Listening to apprentices describe their experiences, it’s not hard to understand why these programs work. “Some days of the week, we learn something that isn’t just for a test next week; it’s a skill that we could actually use the next day at work,” Stephanie Walters, an apprentice at Robert Bosch LLC in Charleston, which makes antilock braking systems, told an audience of educators hosted by the Partnership to Advance Youth Apprenticeships, or PAYA.

Employers and the sponsoring organizations have also helped boost the reputation of apprenticeships by making events like acceptance into a program a cause for celebration. Kathryn Castelloes, director of ApprenticeshipNC, describes how, on the day that high school students sign their apprenticeship contracts, everyone associated gathers together, including parents, and students come up one at a time to be recognized by their new company. Some future apprentices don baseball caps with the company logo. “It’s almost like the NFL draft, the way everybody is recognized and celebrates,” she says.

A few major companies like Siemens have pushed beyond setting up programs just to feed their own pipeline. The Siemens Foundation, a nonprofit in the U.S. linked with the company, wants to make work-study an essential part of secondary schooling in America. “Just a few years ago, we approached our board with what we believe could be a game changer,” David Etzwiler, president of the foundation, said in a recent speech. “We envisioned American high schools across the country offering a new pathway to success for their students, one that supported dual enrollment in college, securing a high school diploma and gaining meaningful paid work experience.” The plan includes partnerships with groups like the National Governors Association, the association of state career and technical training programs, and PAYA.

Siemens itself, meantime, is seeking to expand its apprenticeship efforts to nine states. The push includes providing thousands of career and technical colleges with free licenses to the software that Siemens uses to train apprentices. The focus: middle-skill technical jobs. “In the tech economy, there are half a million open positions, yet only 40,000 computer scientists entering the workforce every year,” says Humpton. “That’s why companies recruiting today must go beyond the typical jobs pipeline and ask, “Who else are we missing?”

Spreading the apprenticeship message is getting easier because of the advantages that the programs bring to regions instituting them. The greater Charlotte area, for instance, now boasts some 200 German firms, employing some 21,000 workers, according to Sven Gerzer, vice president of economic development for the Charlotte Regional Business Alliance. “A unique advantage that draws German companies to the Charlotte region is the array of workforce development programs that incorporate German instructional methods,” Gerzer explains. The region keeps investing in them, including a $25 million technology center at Central Piedmont Community College that serves as a nexus for many.

Businessman Noel Ginsburg, founder of a company called Intertech Plastics, observed the Swiss model of apprenticeships on a visit to the country and created CareerWise Colorado, which became the state’s ambitious apprenticeship effort after he got then-governor John Hickenlooper to endorse it. Here, too, youngsters can obtain an education and certification in a trade without accumulating debt. CareerWise, the so-called intermediary in the program, has signed up more than 100 employers and 16 school districts in just three years and has enlisted 400 apprentices. The goal is to enroll about 10 percent of the state’s high school juniors, or 20,000 students, says chief operating officer Ashley Carter.

A kindred project is emerging in Utah. A Swiss company, Stadler Rail, was having trouble staffing its Salt Lake City plant. Most of its senior executives served apprenticeships in Europe, so the business, joining forces with the Salt Lake City public school district and the city’s community college, decided to start a local apprenticeship system. Students begin as high school seniors and get paid $13 an hour, once they begin apprenticing after graduation, as they take college courses. They finish with an associate’s college degree in advanced manufacturing. A similar statewide plan is ApprenticeNH in the Granite State. Started in 2016, it is run through the New Hampshire community college system. So far, 35 businesses offer about 200 apprenticeships in fields such as manufacturing, construction, and information technology. ApprenticeNH is looking to add 400 more slots in the next few years.

Apprenticeship programs are especially appealing to industrial regions that have hemorrhaged manufacturing jobs. Indiana’s Elkhart County experienced devastating unemployment after the 2008–09 recession, and officials and business leaders began searching for ways to stop the area’s decline. Industry representatives highlighted the need to recruit local workers with the skills to staff more automated and sophisticated plants. After a trip to Germany, local officials developed Careerwise Elkhart County in cooperation with employers and regional school districts. They’re aiming to offer up to 100 ongoing apprenticeships in manufacturing technology, project management, and other areas.

These local efforts are now garnering Washington support. In July 2018, the Trump administration established the National Council of the American Worker, with members including CEOs from companies like Siemens and Lockheed Martin. It aims to create 1 million apprenticeships in America and “change the perception of what it means to be skilled, change the perception of parents, community leaders and educational systems.” To back those efforts, the administration proposed increasing federal funding for career and technical training by $900 million. The administration is also doling out hundreds of millions of dollars in grants to groups around the country to encourage the creation of regional and statewide apprenticeship systems. One recipient is ApprenticeshipNC, which is using $2.3 million from the Labor Department to provide financial assistance to apprentices and to hire coordinators charged with bringing more businesses into the program.

It’s essential work, says Siemens’s Humpton. “We’ve learned that the skills gap cannot be corrected by a strong economy. It can only be corrected by a strong community,” she argues. Across America, employers, educators, and parents are transforming work-study into a true alternative to the four-year college degree.

This article was made possible by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

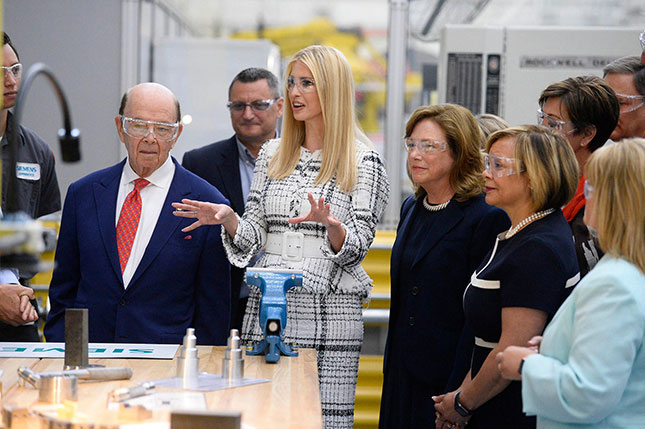

Top Photo: Siemens USA Corporation, with 50,000 employees, was an early advocate for work-study programs in America, allowing students to complete their education while gaining valuable experience. (COURTESY OF SIEMENS)