Incredibly, it wasn’t until I was 19 that I learned that there had been a Holocaust. My hyper-assimilated, New England Jewish family and friends looked only to the present and future. We focused on the polio vaccine that promised to banish the iron lungs that had been our childhood terror. We trusted in the United Nations, whose gleaming buildings my father took me to see when they were brand-new, and from which I came away with hopeful admiration—mixed, however, with a vague sense, which I couldn’t have put into words then, that perhaps an enterprise housed in architecture so grandiosely superhuman, so showy but flimsy, and so modernistically disdainful of the past, might be too utopian to ensure the world peace it envisioned. I know that I read The Diary of Anne Frank back then, but I was probably too young to identify with a girl, so it made no impression.

But as a college freshman, I went to see a movie that had as its unannounced co-feature Alain Resnais’s spare, half-hour documentary Night and Fog, made up of photographs and film clips of the Nazi death camps. Utterly unprepared and unsuspecting, I came abruptly face-to-face with what had actually happened in the very recent past—indeed, was still happening even in the first months of my own life. I came out of the Thalia theater weeping like a baby, forever changed. True, as I learned later, the movie never uttered the word Jew, and the films that General Eisenhower ordered to be made of the liberated camps, so that people would believe the otherwise incredible, were still more gruesome. No matter. I was never the same.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Resnais showed enough—the packed cattle cars; the mounds of shorn human hair, gold dental fillings, wedding rings, worn shoes; the emaciated men in striped pajamas lying miserably shoulder to shoulder on bare wooden bunks stacked to the ceiling as in a battery henhouse; the hopeless victims sitting on surgical tables, castrated or subjected to demonic medical experiments; the crowds of naked women, terrified but trying to preserve a shred of modesty by covering themselves with their hands, as kapos herded them into the “showers,” where, as the gas killed them, their vainly desperate fingernails left scratches on the walls; the chimneys streaming infernal smoke; the Allied bulldozers piling up the wasted dead bodies at the liberation of what the Germans called, with stark precision, the Vernichtungslagers, the “becoming-nothing camps.” And, of course, we saw the tattooed serial numbers, the ledgers that recorded them, the soap and lampshades made from the dead: a modern, methodical, highly organized industrial society had done this.

I knew that the world had not always been as secure and flourishing as the mid-century America I grew up in: my mother told many stories of the Great Depression, with all its hardships and fears, though I discounted her claim that, whenever her mother-in-law had a joint of meat to roast, she lacked a nickel for the gas meter to cook it with. But I always knew that prosperity was not a given, and that what had happened before could happen again. But evil of such enormity as the Nazis? I never dreamed it possible, and learning that it had actually happened, in my own lifetime and to my own kinsmen, turned my worldview upside-down.

If I had to pick one image that summed up the mid-century American spirit I grew up in, it would be Ronald Reagan, as host of television’s weekly GE Theater, intoning reassuringly, “At General Electric, progress is our most important product.” Progress! And to us, that didn’t just mean the scientific progress of the Salk and then the Sabin polio vaccines or the mighty rockets thundering into the unknown from Cape Canaveral. We also believed in the moral progress that the UN supposedly embodied. Was not American anti-Semitism evaporating like morning fog in those years? Did not the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board school-desegregation decision herald the end of U.S. racism? Did not the arc of history—to quote the German-inspired illusion of a recent president—bend toward justice?

I went into the Thalia theater with those rosy hopes as unquestioned bedrock assumptions. I came out with such certitude shattered. If so advanced a society as Germany’s—with so glorious a past in music and philosophy, such mighty achievements in science and industry—could do this in modern times, all talk of moral progress was just wind.

I was hardly the first young person to have such a rude awakening, nor will I be the last. The greatest poem by the twentieth century’s greatest poet, William Butler Yeats’s “Nineteen Hundred and Nineteen,” describes how the First World War sparked just such a disillusionment in his generation—at least, those of it who survived. They had grown up with complacent pride in the immense achievements of the liberal long nineteenth century:

We too had many pretty toys when young:

A law indifferent to blame or praise,

To bribe or threat; habits that made old wrong

Melt down, as it were wax in the sun’s rays;

Public opinion ripening for so long

We thought it would outlive all future days.

O what fine thought we had because we thought

That the worst rogues and rascals had died out.

Echoing his revered fellow Irishman Edmund Burke, Yeats had believed that custom, culture, and the rule of law had thoroughly legitimized dynasties born from brutal conquest, civilizing today’s kings into mild and just monarchs, and softening knights and serfs into gentlemen and citizens. An immense achievement—with the single caveat that “no cannon had been turned/ Into a ploughshare,” though that seemed a mere oversight at the time.

And then, seemingly out of nowhere in the midst of this prosperous, complacent, decades-long peace, erupted the war, which killed the flower of Europe’s young men, but not before they had suffered cold, wet, privation, gas, and fear in the muddy, rat-swarming trenches, which failed to protect so many from the shells and sharpshooters of the enemy. Yeats writes:

Now days are dragon-ridden, the nightmare

Rides upon sleep: a drunken soldiery

Can leave the mother, murdered at her door,

To crawl in her own blood, and go scot-free;

The night can sweat with terror as before

We pieced our thoughts into philosophy,

And planned to bring the world under a rule,

Who are but weasels fighting in a hole.

The survivors survived but never recovered. They bore indelible scars, if not on their flesh then on coarsened, disillusioned, selfish, and misanthropic souls.

We, who seven years ago

Talked of honour and of truth,

Shriek with pleasure if we show

The weasel’s twist, the weasel’s tooth.

Vanished along with its civility were the Victorian beliefs in progress, benevolence, and Imperial Europe’s civilizing mission. And for the soldiers’ younger brothers and sisters, gone, too, were all ideals. Virtue? Truth? Wisdom? The new culture’s keynote was cynical mockery of such moral and intellectual achievements as mankind can show. The West had entered an age of contempt for the great, the wise, and the good, whose thoughts and deeds seemed irrelevant to the postwar weasel-world. Bereft of ideals, the mockers felt contempt for themselves as well—a state of mind that you can still see on any political-comedy TV show today. And such a culture, in Yeats’s glum summation, threatened to devolve further into blind lust, blind anger, and blind stupidity.

The imperial civilizing mission! All efforts to bring the world under a rule, from the UN to the EU, end in disillusionment, but European colonialism was misguided in its own specially cynical, dishonest way. Until academic political correctness sent it to stand in the corner for being racist, Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness—as powerful a prose masterpiece as we have—was our hardest-hitting indictment of this fraud. “All Europe contributed to the making of Kurtz,” writes Conrad of his charismatic Belgian protagonist, born to a half-English mother and half-French father. And what had all Europe made? A Congo-bound “emissary of pity, of science, of progress,” with “higher intelligence, wide sympathies, a singleness of purpose” needed “for the guidance of the cause intrusted us by Europe,” a Kurtz associate remarks, with a sneer in his voice that puts the reader on guard. For the grandiloquently named International Society for the Suppression of Savage Customs, Kurtz wrote a pamphlet arguing that white Europeans “must necessary appear to them [savages] in the nature of supernatural beings—we approach them with the might as of a deity. . . . By the simple exercise of our will we can exert a power for good practically unbounded.”

On the ground, however, the nation-building uplift looked less promising. Of a planned railway through the jungle, the only signs were regular and apparently ineffectual blasting of a cliff that seemed in the way of nothing, an overturned railcar, some holes in the ground, one filled with pottery drainage pipes smashed into useless fragments, and a new slavery, with supposed African criminals—breakers of laws they didn’t comprehend—chained together by the neck and bearing baskets of earth from the blasting. Other blacks, worn out by work on the hopeless project supposed to uplift them, lay dying slowly in the forest, “shadows of disease and starvation.”

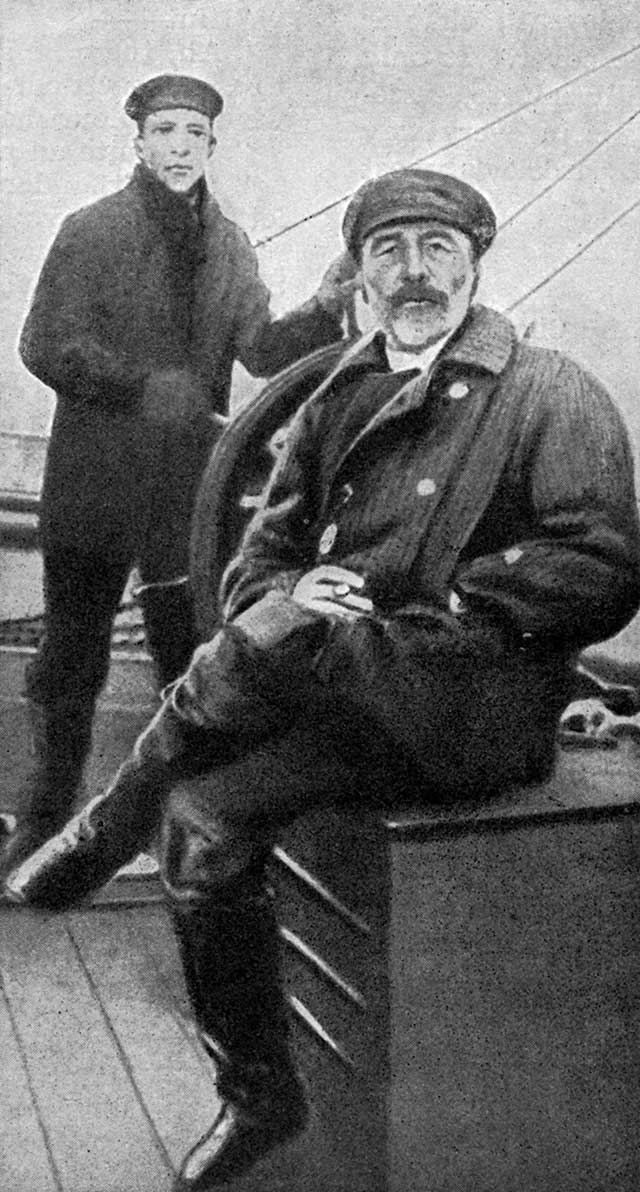

But the railway-building wasn’t just feckless. It was a mask for the real business of Belgian imperialism, arguably Europe’s nastiest. The goal: “To tear treasure out of the bowels of the land,” with no more moral purpose than “burglars breaking into a safe.” To the narrator of Conrad’s 1899 novella—a sea captain named Marlow, recounting his command of a rusty steamer taking an exploring party up the Congo, as Conrad himself had been and done—all this resembled the Roman colonization of Britain, which, in ancient times, prefigured Conrad’s Africa in being “one of the dark places of the world,” a wilderness peopled by savages. The Romans “grabbed what they could get,” Conrad writes. “It was just robbery with violence, aggravated murder on a great scale.”

Western civilization’s godlike power, the once-philanthropic Kurtz discovered, is morally neutral, as ready to work evil as good. We approach undeveloped tribesmen in the aspect of a deity, able to bend them to our will—chiefly, in this case, because of the technological marvel of our Martini-Henry rifles? Exercise a little of that power, and you develop a taste for exercising yet more of it, Kurtz found, until he really made himself into a god to the local tribesmen, whose chiefs crawled submissively to his throne on all fours, while their subjects become Kurtz’s army, raiding the jungle villages for ivory to send downriver to Europe. The deified Kurtz became the most successful—meaning rapacious—imperialist of them all.

His lust for power—the simple exercise of his will—grew limitless: the lasting image of him in Marlow’s mind is a mouth voraciously open, “as though he had wanted to swallow all the air, all the earth, all the men before him.” He spoke as if “everything belonged to him.” He liked to “preside at certain midnight dances ending with unspeakable rites, which . . . were offered up to him,” offerings that doubtless included the severed heads stuck on poles around his house, heads of men he had killed just to show that he could. And the power and rapacity included sex, too, as Conrad makes clear in his description of a magnificently statuesque woman, as bejeweled as a queen but otherwise naked, passionately devoted to Kurtz.

All this voracity “showed that Mr. Kurtz lacked restraint in the gratification of his various lusts, that there was something wanting in him,” Marlow drily judges. The wilderness “had whispered to him things about himself which he did not know, things of which he had no conception,” Marlow recounts, “and the whisper had proved irresistibly fascinating.” In the end, Kurtz faces up to what he has done and become. At the bottom of his philanthropic article for the International Society for the Suppression of Savage Customs about Europe’s boundless power to civilize African tribesmen, he scrawls, “Exterminate all the brutes!” And his last whisper judges himself just as harshly: “The horror! The horror!”

Civilized Europeans have no occasion to recognize the lusts hidden within them, Conrad thinks, writing just before Sigmund Freud began disclosing impulses that people would prefer not to admit were part of their nature. And how would they know, in their cities where they walk “delicately between the butcher and the policeman, in the holy terror of scandal and gallows and lunatic asylums”—the butcher who shields us from the knowledge that we live by eating other creatures slaughtered by the millions for us, cut up into pieces and sauced so that we don’t recognize what is actually on our plates; the policeman, who, along with public opinion and the threat of legal punishment, makes most of us suppress our lusts and rages below the level of consciousness and certainly below the level of action?

But in turn-of-the-century Africa, all was different, as Marlow’s passengers discovered as they steamed upriver, penetrating ever deeper into the jungle, “wondering and secretly appalled” by the strangeness of what they saw. “The earth seemed unearthly. We are accustomed to look on the form of a conquered monster, but there—there you could look at a thing monstrous and free,” Conrad writes. And “the men were—No, they were not inhuman,” cannibals though they might be. “They howled and leaped, and spun, and made horrid faces; but what thrilled you was the thought of their humanity—like yours—the thought of your remote kinship with this wild and passionate uproar,” which, however dimly, you could comprehend.

“You wonder I didn’t go ashore for a howl and a dance?” Marlow asks. “Well, no—I didn’t.” Not that he doesn’t recognize an appeal in “the fiendish row” onshore; “but I have a voice, too,” capable of asserting “a deliberate belief”—not an attitude, “not a sentimental pretence but an idea: and an unselfish belief in the idea.” And his idea is civilization, enlightenment, efficiency, deferral of gratification, the work ethic, which he, like so many fellow Victorians, believed allowed each individual to discover and realize whatever gifts and talents lay within him, while at the same time improving or enriching the world. So firmly does Conrad hold these ideals that he respects and admires even a slightly comic (now even clichéd) embodiment of them in the Congo company’s accountant, with his perfectly brushed hair, impeccably starched and snowy linen, shiny boots, ledgers in apple-pie order, all proof that “in the great demoralization of the land he kept up his appearance. That’s backbone. His starched collars and got-up shirt fronts were achievements of character.”

But you can’t count on such an achievement lasting forever. Yes, England began as one of the dark places of the world and became a source of enlightenment, “but it is like a running blaze on a plain, like a flash of lightning in the clouds,” says Marlow. “We live in the flicker—may it last as long as the old earth keeps rolling!” To which Yeats would reply that it went out in 1914, and as British foreign minister Lord Grey remarked as the war-clouds gathered that summer, “The lamps are going out all over Europe: we shall not see them lit again in our life-time.” And they went out again in Germany and Central Europe in the 1930s and ’40s.

Why am I telling you all this? Because I fear that, except for a few of us remaining graybeards and some immigrants from the world’s manifold tyrannies and anarchies, most Americans are too young to remember, even vicariously, the ills that the world can inflict and the effort it takes to withstand and restrain them. They have studied no history, so not only can they not distinguish Napoleon from Hitler, but also they have no conception of how many ills mankind has suffered or inflicted on itself and how heroic has been the effort of the great, the wise, and the good over the centuries to advance the world’s enlightenment and civilization—efforts that the young have learned to scorn as the self-interested machinations of dead white men to maintain their dominance. While young people are examining their belly buttons for microaggressions, real evil still haunts the world, still inheres in human nature; and those who don’t know this are at risk of being ambushed and crushed by it.

Slogans, placards, and chants won’t stop it: the world is not a campus, Donald Trump is not Adolf Hitler, the Israelis are not Nazis. Moreover, it is disgracefully, cloyingly naive to think—as the professor hurt in the melee to keep Charles Murray from addressing a Middlebury College audience recently put it in the New York Times—that “All violence is a breakdown of communication.” An hour’s talk over a nice cup of tea would not have kept Vladimir Putin from invading Ukraine, or persuaded an Islamist terrorist not to explode his bomb. Misunderstanding does not cause murder, and reasoned conversation does not penetrate the heart of darkness.

Much as I revere Yeats, I do not share his theory that history is cyclical, with civilizations rising and decaying, until something new arises from the ashes. Perhaps it’s the ember of mid-century optimism still alive in me, but I can’t believe that “All things fall and are built again.” I don’t want to believe, with Conrad in his darkest moods, that “we live in the flicker,” that moments of enlightenment shine but briefly between the eras of ignorance and barbarism.

But who can deny that there are some truths that history has taught—the Copybook Headings, Rudyard Kipling calls them—that we ignore at our peril? Has not history’s recurring tale been, as Kipling cautions, that “a tribe had been wiped off its icefield, or the lights had gone out in Rome?” So beware of UN-style promises of perpetual peace through disarmament, which you’ll find will have “sold us and delivered us bound to our foe.” Beware of a sexual freedom that will end when “our women had no more children and the men lost reason and faith.” Don’t believe that you can achieve “abundance for all,/ By robbing selected Peter to pay for collective Paul,” because the eternal truth is, “If you don’t work you die.” And the truth that history teaches is that when

the brave new world begins

When all men are paid for existing and no man must pay for his sins,

As surely as Water will wet us, as surely as Fire will burn,

The Gods of the Copybook Headings with terror and slaughter return!

Man is a believing animal. We live by some of those beliefs, made plausible by the labors of the good and the great to embody them, and of the wise to explain how they have created a freer, more prosperous, more just, and more fulfilling life for mankind. But other beliefs, the stock-in-trade of the world’s deluded or power-hungry demagogues and charlatans, will kill us. Our nation’s fate depends on relearning the difference.

Top Photo: The realization that man can do this to man—and did it to millions at the Nazi death camps, such as Majdanek (left)—revolutionizes your worldview. (© RIA-NOVOSTI / THE IMAGE WORKS)