In Illinois in late June, the state legislature passed, and the governor signed, a makeshift budget to fund essential state operations for six months. The deal came after the state had gone a year and a half without a budget. The impasse resulted from an ongoing battle between Republican governor Bruce Rauner and Democratic house speaker Michael Madigan. Rauner, a successful businessman, won election in 2014 on a platform to change the way Illinois did business. Rather than betray his voters, Rauner has held firm to his demand that parts of his “Turnaround Agenda”—which includes changes to workmen’s compensation and public-employee unionism, along with tort reform—be part of any state budget. On the other side, Madigan, who represents a coalition of Democrats and unions, wants more tax revenue for his “spending plan” but none of Rauner’s initiatives. Rauner and Madigan faced intense pressure to adopt a stopgap measure and avoid taking the blame if schools failed to open in the fall, enrollment fell at state universities, road repairs stopped, and prisoners in state penitentiaries went hungry for lack of food. Yet as soon as the budget measure passed, both sides returned to the battlefield, raising the question of when, if ever, the state will return to normalcy.

Illinois currently holds the dubious distinction of being the most fiscally derelict state in America. In 2015, Moody’s downgraded Illinois’ general-obligation bonds from A3 to Baa1, the lowest ranking among the 50 states. The state’s pension systems are only 40 percent funded, the worst ratio in the country. Forbes rated Illinois’ business climate 38th among states last year. Chicago, the state’s economic engine, has been cratering under the weight of huge pension costs, and had to enact a $500 million property-tax increase last year. In addition, Chicago’s schools are in crisis, and—most disturbing of all—the city has watched its crime rate explode. The migration rate out of Illinois over the last five years has been the highest of any state.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

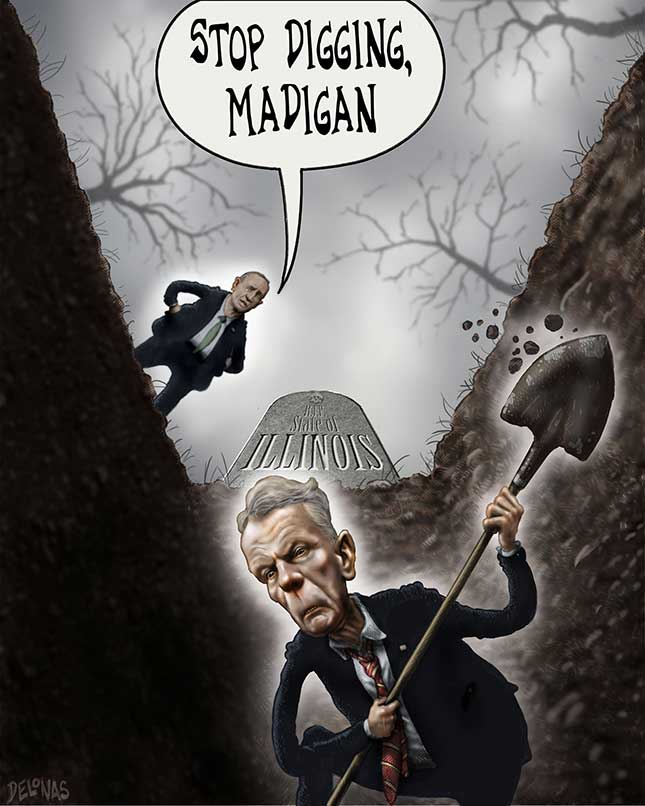

Digging so deep a fiscal and economic hole takes effort. Many people doubtless share some of the culpability. But if one person should be singled out as responsible for Illinois’ political and economic mess, it would be House Speaker Madigan. Unlike Rauner, who just arrived on the political scene, Madigan is at the heart of Illinois’ political establishment. Chicago magazine has long ranked him among the “most powerful” people in the Windy City.

Madigan, 74, has been involved in electoral politics for 43 years and has served as speaker of the Illinois House for 31 of those—making him the longest-serving state house speaker in U.S. history. His duties hardly stop there. He is also the chairman of the state Democratic Party, a partner in Chicago’s most successful property-tax law firm, and—last, but not least—a committeeman for Chicago’s 13th Ward, a post he has held since he was 27. These four positions and their associated networks of patronage appointees, legislative staffers, corporate lobbyists, campaign donors, industry clients, and family members are what some in Illinois refer to as “Madiganistan” or the “Madigan industrial complex.”

Despite his outsize presence in the state, few have heard of Madigan outside Illinois. The obscurity is understandable. Madigan is an old-school party politician. He still represents the once–Irish Catholic but now heavily Latino Clearing neighborhood, where he grew up, on the Southwest Side of Chicago, which is part of the “bungalow belt.” After attending Notre Dame and Loyola University Law School, he learned how to exercise political power at the feet of longtime Chicago mayor Richard J. Daley. (Madigan’s father knew Daley from the days when they both held patronage jobs in Cook County.)

Daley was the boss of the famous (or infamous) Democratic Party machine that dominated not just city government but the state government as well. The first lesson of machine politics is that getting and holding power is the most important thing. The second lesson is that to stay in charge, one must reward friends and either punish or co-opt enemies. Madigan appears to have taken both lessons to heart and applied them with ruthless efficiency. Over his long career, he has created a statewide party machine to replace the one in the city. It has a number of interlocking parts, each allowing him to follow the dictums of bossism.

Madigan claims that acceding to Rauner’s agenda would force him to abandon his core beliefs, but his politics, like those of the party bosses of yesteryear, are not about principles. Philip Rock, a former state senator, has written that Madigan “is very difficult to label” and that “it would be impossible to identify him with one narrow political philosophy or ideology.” For Madigan, politics is about power, not policy. Neither his constituents nor anyone else really knows his positions, if he has them, on any number of issues. Madigan has never offered a laundry list of programs that he’d like to see enacted. He’s definitely not a warrior against corruption or an advocate of transparency and open government. He’s no critic of capitalism and isn’t shy about making a lot of money.

While Illinois ethics laws don’t require Madigan to disclose his outside income, everyone agrees that he’s made a fortune at his law firm, Madigan and Getzendanner, which seeks to reduce the property-tax bills of its clients. In 2010, the firm represented 45 of the 150 most valuable commercial buildings in Chicago, according to the Chicago Tribune. Like Tammany Hall politicians of yesteryear, Madigan practices what George Washington Plunkitt called “honest graft.”

Madigan exercises power as if it were still the era of smoke-filled rooms. He prefers closed-door meetings to the media spotlight and is tightlipped when speaking to the press. But he doesn’t need the media to get his way. His years of experience mean that he knows the legislative process in Illinois better than anyone. He’s obsessively detail-oriented and famous for reading the state budget line by line. “He knows more about the workings of the General Assembly than anyone, on any issue, at any time,” says Jack Franks, a Democratic state representative.

The keystone of the Madigan machine is his position as house speaker. He rose to that post, in part, because his Southwest Side seat is extremely safe. With little effort, he could be reelected every two years by as few as 30,000 voters. Such leverage enabled him to work his way up the party leadership ladder. First elected to the house in 1970, he became speaker in 1983, losing the position only briefly, when Republicans won control of the body for one term in 1994.

Madigan has methodically concentrated power in the speaker’s office. For example, he stripped away the ability to appoint legislative staff from committee chairmen and placed it in the Committee on Committees, which he controls. He also revised house rules to let him unilaterally change committee members, so he could substitute those sympathetic to him on a given issue for those less well-disposed. Finally, Madigan bottles up legislation that he opposes through the Rules Committee, which, chaired by a top lieutenant, is the first stop that any bill makes, once it is introduced.

Nowadays, Madigan controls all the levers of legislative power. Under house rules, he can set the legislative agenda, determining which bills move forward. Lobbyists know this. With influence so concentrated, they have little need to try to persuade other legislators. Therefore, they either give money to one of the campaign funds that Madigan controls or solicit his advice about where the interests they represent should send their checks. Some refer to the system as “one-stop shopping.” Madigan thus holds a great deal of sway over other legislators; if they want to see their projects become law, they need to earn his goodwill.

Madigan’s position as speaker depends, of course, on the Democratic majority in the house, which he has tirelessly sought to expand, especially by inserting himself into the redistricting process. The result: a majority that has now become a supermajority, with Democrats controlling 71 of 118 seats. Unsurprisingly, Madigan has fiercely opposed efforts to shift control of redistricting to an independent commission.

Perhaps the primary way Madigan exercises control over “his” majority is through campaign funds. One source of that money comes directly from his campaign coffers. Running largely unopposed year after year—or against fake candidates placed on the ballot by his supporters—has made it possible for Madigan to raise, by one estimate, more than $35 million since 1994. In addition, as chairman of the Illinois Democratic Party, he has access to party accounts and can funnel money to favored candidates. The state party was, for a while, run out of Madigan’s office in Springfield and now makes its headquarters in a small office building near the capitol, where Madigan’s campaign finance team works. Campaign cash can buy a lot of loyalty among legislators.

Another tool in Madigan’s kit is pork-barrel spending, which he often directs to party members in tough reelection contests. For instance, in 1999, the state government created the Illinois Fund for Infrastructure, Roads, Schools, and Transit (IllinoisFIRST). This five-year, $12 billion pot of money was dedicated to public works. Political scientists Michael Herron and Brett Theodos found that the funds were distributed by Madigan tactically to assist Democratic legislators facing tough reelection bids, rather than to districts that most needed the money. For Madigan, policymaking is about maintaining power, not trying to serve the public interest.

Madigan’s big house majority offers benefits that extend well beyond one chamber of the legislature. The current president of the state senate, John Cullerton, was a Madigan protégé who cut his teeth as Madigan’s floor leader in the house. (Cullerton is also Madigan’s son’s godfather.) Madigan has similarly cultivated a huge cadre of staffers, former legislators, and lobbyists now working in other parts of government. No one in Illinois has a wider network of contacts.

The next crucial component of the Madigan machine is a small army of patronage workers—estimated to be about 400 current or retired government employees. Known locally as “Madigoons,” these workers hold or held jobs at the city, county, and state levels. The most notorious patronage outpost might be Chicago’s Bureau of Electricity, dubbed “Madigan electric” for the number of loyalists he has toiling there. These foot soldiers can be counted on for get-out-the-vote drives and other campaign operations in nearly every part of the state, at every level of government.

As Madigan’s patronage appointees move between agencies and levels of government, the speaker regularly intervenes to secure them pay raises, promotions, and new jobs. Some workers have held as many as a dozen different government positions over the course of their careers. Many have questionable qualifications for the posts they hold and probably spend more time on party politics than on their nominal jobs. All devote some of their salaries to Madigan’s campaign funds.

Many of Madigan’s own family members hold politically powerful positions throughout Illinois. His wife, Judy, was appointed a member of the Illinois Arts Council in 1976 and has served as chairwoman for the last 23 years. Madigan’s adopted daughter, Lisa Madigan, is Illinois attorney general and a likely future gubernatorial candidate. His three other children’s careers, and those of their spouses, are also intertwined with his machine. Tiffany Madigan is a lawyer at a big firm that has donated money to Madigan’s campaigns. Her husband, Jordan Matyas, started out as a staffer in the speaker’s office, was chief of staff of the Regional Transportation Authority, and has now opened his own law firm that advertises his knowledge of state politics. Nicole Madigan is a real-estate lawyer who worked for a firm that contributed to Lisa’s campaign war chest and is now general counsel to a real-estate management firm in Chicago. Andrew Madigan is an analyst at a financial-services firm that receives state contracts and deals with city bonds.

“Perhaps the primary way Madigan exercises control over ‘his’ majority is through campaign funds.”

Madigan’s machine extends to the judicial branch. His otherwise obscure post as ward committeeman puts him in a position to help pick lawyers slated to be judges on the circuit court of Cook County. Lawyers who want to become judges must work for, and make contributions to, the Democratic Party to get their names on the “Madigan List.” From 2003 to 2011, according to the Chicago Tribune, Madigan recommended 37 attorneys for the bench; 25 wound up selected. Several more were later nominated.

Cook County judges have, in turn, helped stymie changes that Madigan opposes. In July, one judge declared illegal a constitutional amendment to change the state’s redistricting process, which had been set to appear on the ballot this fall. This was the second time that judges had thrown out such a referendum. A longtime Madigan ally, Michael Kaspar, general counsel for the Illinois Democratic Party, brought the lawsuit to prevent the measure from appearing on the ballot.

The results of Madigan’s reign have not been pretty. Over the past five years—and perhaps far longer, depending on the accounting—Madigan’s Democratic supermajority in the house and Cullerton’s Democratic majority in the senate have not passed a single balanced budget. The latest budget battle is only the most recent example of a state unable to get its fiscal house in order. Illinois has for years failed to make the annual required contribution to its pension systems. Pension expert Alicia Munnell notes that “fiscal discipline [appears] not to be part of the state’s culture.” Under Madigan, the Democrats found that shorting the fund freed up money for other things. Madigan and his allies could avoid the hard decisions of making real cuts or raising revenue to pay for their policy choices.

That Madigan has not acted to address the state’s fiscal problems is not for a lack of the means to do so. His power was on full display this past May, when the Democratic house majority introduced, debated, and passed a 500-page budget in less than three hours. Of course, the problem with that budget (and the two prior budgets)—and the reason that Governor Rauner wouldn’t sign it—was that it proposed to spend $39 billion, while conceding that the state would collect only $32 billion in revenue. A budget that’s $7 billion out of balance isn’t just bad policy; it violates the state constitution.

Madigan’s concentration of power has rendered representative democracy in Illinois somewhat of a mirage. Citizens in the Land of Lincoln elect people to the house—but once they get to Springfield, they don’t do much. Committees rarely meet. Reform bills never go anywhere or are easily lost in the institution’s bureaucratic shuffle.

Madiganistan has also given rise to a number of “small” scandals, none of which has been big enough to shake the speaker’s grip on power. For example, it was discovered that Madigan and other legislators used their influence to place the children of major campaign contributors on a special admissions track at the University of Illinois. From 2004 to 2009, some 800 students with connections to politicians were placed on a “clout list” and often offered admission. Some had questionable academic qualifications. Of the 28 students Madigan lobbied university officials to admit, all were children of major campaign donors. One parent, a prominent lawyer, gave as much as $71,800 to Madigan-controlled funds. (He also gave generously to Lisa Madigan’s campaign for attorney general.) At least 23 of the 28 were admitted as undergraduates or to graduate programs in business or law. Madigan’s clout, as relayed through the university’s lobbyists, was no doubt enhanced by the fact that he has enormous influence on state funding of the university, which constitutes some 16.5 percent of the school’s budget.

A patronage scandal at the Metra, the Regional Transportation Authority, erupted after the departure of CEO Alex Clifford (who received an $817,000 severance package). Madigan reportedly asked Clifford for raises and promotions of political associates, for whom he had secured jobs at the agency. Clifford, who had been brought in to improve the authority’s efficiency, refused, writing a scathing memo that, he later claimed, caused his dismissal. One of Madigan’s foot soldiers at the center of the Metra scandal, Patrick Ward, had faithfully donated some $16,525 to the politician’s various campaign funds between 1999 and 2012. Ward could afford such campaign spending on a salary of less than $70,000 a year because, in addition to his Metra salary, he was receiving a $57,000 annual pension from the city of Chicago. Ward survived the scandal intact. Madigan recommended him for a state supervisor’s job that was created only after he interviewed for it and for which no other applicants were considered. The job description apparently leaves Ward with no one to report to and no one reporting to him.

The patronage operation at Metra went back years. The assembly’s inspector general investigated and learned that Metra’s chairperson would go to Madigan’s office, ostensibly to talk about state issues, and leave with the names of workers whom Madigan wanted hired or promoted. Bizarrely, we know about this episode only because Madigan himself requested the inspector general’s report in order to clear himself of any legal liability. Authorities treated Madigan’s repeated interventions to secure jobs, promotions, and raises for his allies as standard practice, not in violation of any of the state’s weak ethics laws. Given that the attorney general is Madigan’s daughter, no one expected a rigorous investigation to emerge from that quarter.

Finally, there was Chicago’s red-light camera scandal. One of Madigan’s 13th Ward precinct captains, John Bills, while working as a city transportation official, rigged the contracting process to ensure that Redflex Traffic Systems won the city’s $131 million contract for a camera system, in exchange for kickbacks that federal prosecutors said totaled some $2 million, including $600,000 in cash and a condo in Arizona. Bills also encouraged the company to hire a lobbyist with strong ties to Madigan and lobbied Madigan directly to sponsor legislation that would allow Chicago to install speed cameras, which would help Redflex expand its business with the city. Madigan sponsored such legislation, and Governor Pat Quinn signed it into law in 2012. Bills received a ten-year prison sentence.

If Madiganistan is about anything—beyond self-interest—it is about cost shifting. By shorting pension funds, Madigan has transferred the tax burden to future generations. His law firm reduces property taxes on commercial buildings, which inevitably means that those costs will be borne by other property-tax payers. His patronage appointments spread the costs of his campaign operations onto different units of government—and onto taxpayers. The inevitable scandals cost taxpayers a bundle in legal fees, severance packages, and hush money. Shifting the costs to enemies in order to reward friends is one element of what has come to be known as “the Chicago way.”

Governor Rauner was elected to reform the machine-style political culture that has rendered Illinois so dysfunctional. He’s still fighting. But the vested interests, represented and exemplified by Michael Madigan, are deeply entrenched—and they hold a lot of cards. Illinois politics is an outlier in many respects, but Madiganistan is only a more extreme version of what goes on in other deep-blue states, such as New York and California. All are plagued with a toxic combination of undemocratic practices and unsustainable fiscal policies. Sooner or later, something has to give.