Borders are in the news as never before. After millions of young, Muslim, and mostly male refugees flooded into the European Union last year from the war-torn Middle East, a popular revolt arose against the so-called Schengen Area agreements, which give free rights of movement within Europe. The concurrent suspension of most E.U. external controls on immigration and asylum rendered the open-borders pact suddenly unworkable. The European masses are not racists, but they now apparently wish to accept Middle Eastern immigrants only to the degree that these newcomers arrive legally and promise to become European in values and outlook—protocols that the E.U. essentially discarded decades ago as intolerant. Europeans are relearning that the continent’s external borders mark off very different approaches to culture and society from what prevails in North Africa or the Middle East.

A similar crisis plays out in the United States, where President Barack Obama has renounced his former opposition to open borders and executive-order amnesties. Since 2012, the U.S. has basically ceased policing its southern border. The populist pushback against the opening of the border with Mexico gave rise to the presidential candidacy of Donald Trump—predicated on the candidate’s promise to build an impenetrable border wall—much as the flood of migrants into Germany fueled opposition to Chancellor Angela Merkel.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Driving the growing populist outrage in Europe and North America is the ongoing elite push for a borderless world. Among elites, borderlessness has taken its place among the politically correct positions of our age—and, as with other such ideas, it has shaped the language we use. The descriptive term “illegal alien” has given way to the nebulous “unlawful immigrant.” This, in turn, has given way to “undocumented immigrant,” “immigrant,” or the entirely neutral “migrant”—a noun that obscures whether the individual in question is entering or leaving. Such linguistic gymnastics are unfortunately necessary. Since an enforceable southern border no longer exists, there can be no immigration law to break in the first place.

Today’s open-borders agenda has its roots not only in economic factors—the need for low-wage workers who will do the work that native-born Americans or Europeans supposedly will not—but also in several decades of intellectual ferment, in which Western academics have created a trendy field of “borders discourse.” What we might call post-borderism argues that boundaries even between distinct nations are mere artificial constructs, methods of marginalization designed by those in power, mostly to stigmatize and oppress the “other”—usually the poorer and less Western—who arbitrarily ended up on the wrong side of the divide. “Where borders are drawn, power is exercised,” as one European scholar put it. This view assumes that where borders are not drawn, power is not exercised—as if a million Middle Eastern immigrants pouring into Germany do not wield considerable power by their sheer numbers and adroit manipulation of Western notions of victimization and grievance politics. Indeed, Western leftists seek political empowerment by encouraging the arrival of millions of impoverished migrants.

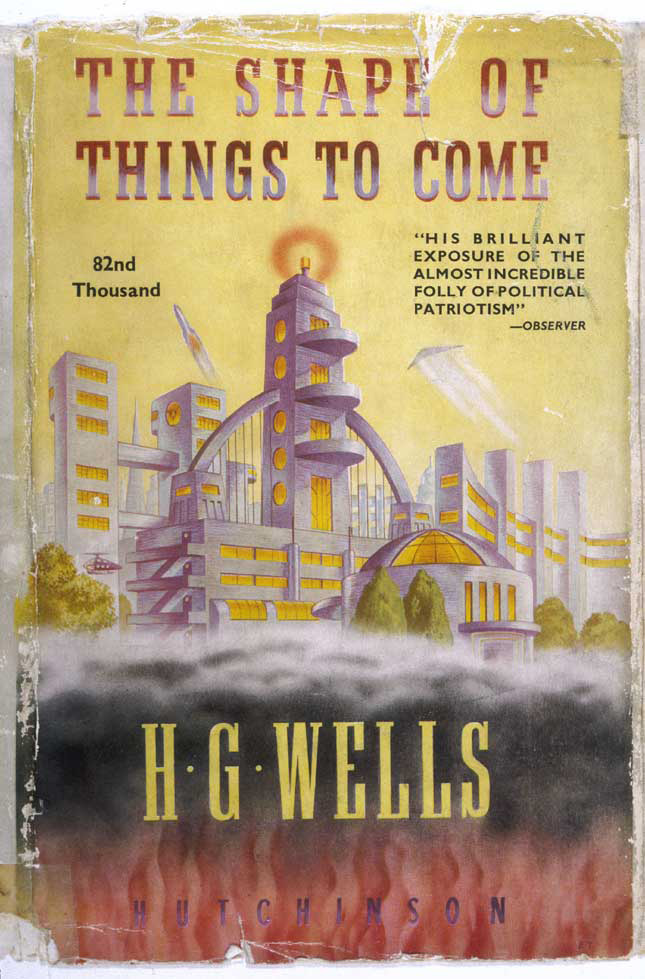

Dreams of a borderless world are not new, however. The biographer and moralist Plutarch claimed in his essay “On Exile” that Socrates had once asserted that he was not just an Athenian but instead “a citizen of the cosmos.” In later European thought, Communist ideas of universal labor solidarity drew heavily on the idea of a world without borders. “Workers of the world, unite!” exhorted Marx and Engels. Wars broke out, in this thinking, only because of needless quarreling over obsolete state boundaries. The solution to this state of endless war, some argued, was to eliminate borders in favor of transnational governance. H. G. Wells’s prewar science-fiction novel The Shape of Things to Come envisioned borders eventually disappearing as elite transnational polymaths enforced enlightened world governance. Such fictions prompt fads in the contemporary real world, though attempts to render borders unimportant—as, in Wells’s time, the League of Nations sought to do—have always failed. Undaunted, the Left continues to cherish the vision of a borderless world as morally superior, a triumph over artificially imposed difference.

Yet the truth is that borders do not create difference—they reflect it. Elites’ continued attempts to erase borders are both futile and destructive.

Borders—and the fights to keep or change them—are as old as agricultural civilization. In ancient Greece, most wars broke out over border scrubland. The contested upland eschatia offered little profit for farming but possessed enormous symbolic value for a city-state to define where its own culture began and ended. The self-acclaimed “citizen of the cosmos” Socrates nonetheless fought his greatest battle as a parochial Athenian hoplite in the ranks of the phalanx at the Battle of Delium—waged over the contested borderlands between Athens and Thebes. Fifth-century Athenians such as Socrates envisioned Attica as a distinct cultural, political, and linguistic entity, within which its tenets of radical democracy and maritime-based imperialism could function quite differently from the neighboring oligarchical agrarianism at Thebes. Attica in the fourth century BC built a system of border forts to protect its northern boundary.

Throughout history, the trigger points of war have traditionally been such borderlands—the methoria between Argos and Sparta, the Rhine and Danube as the frontiers of Rome, or the Alsace-Lorraine powder keg between France and Germany. These disputes did not always arise, at least at first, as efforts to invade and conquer a neighbor. They were instead mutual expressions of distinct societies that valued clear-cut borders—not just as matters of economic necessity or military security but also as a means of ensuring that one society could go about its unique business without the interference and hectoring of its neighbors.

Advocates for open borders often question the historical legitimacy of such territorial boundaries. For instance, some say that when “Alta” California declared its autonomy from Mexico in 1846, the new border stranded an indigenous Latino population in what would shortly become the 31st of the United States. “We didn’t cross the border,” these revisionists say. “The border crossed us.” In fact, there were probably fewer than 10,000 Spanish-speakers residing in California at the time. Thus, almost no contemporary Californians of Latino descent can trace their state residency back to the mid-nineteenth century. They were not “crossed” by borders. And north–south demarcation, for good or evil, didn’t arbitrarily separate people.

“What we might call post-borderism argues that boundaries even between distinct nations are mere artificial constructs.”

The history of borders has been one of constant recalibration, whether dividing up land or unifying it. The Versailles Treaty of 1919 was idealistic not for eliminating borders but for drawing new ones. The old borders, established by imperial powers, supposedly caused World War I; the new ones would better reflect, it was hoped, ethnic and linguistic realities, and thus bring perpetual peace. But the world created at Versailles was blown apart by the Third Reich. German chancellor Adolf Hitler didn’t object to the idea of borders per se; rather, he sought to remake them to encompass all German-speakers—and later so-called Aryans—within one political entity, under his absolute control. Many nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century German intellectuals and artists—among them the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, historian Oswald Spengler, and composer Richard Wagner—agreed that the Roman Empire’s borders marked the boundaries of civilization. Perversely, however, they celebrated their status as the unique “other” that had been kept out of a multiracial Western civilization. Instead, Germany mythologized itself as racially exceptional, precisely because, unlike other Western European nations, it was definable not only by geography or language but also by its supposed racial purity. The fairy-tale origins of the German Volk were traced back before the fifth century AD and predicated on the idea that Germanic tribes for centuries were kept on the northern and eastern sides of the Danube and Rhine Rivers. Thus, in National Socialist ideology, early German, white-skinned, Aryan noble savages paradoxically avoided a mongrelizing and enervating assimilation into the civilized Roman Empire—an outcome dear to the heart of Nazi crackpot racial theorist Alfred Rosenberg (The Myth of the Twentieth Century) and the autodidact Adolf Hitler. World War II was fought to restore the old Eastern European borders that Hitler and Mussolini had erased—but it ended with the creation of entirely new ones, reflecting the power and presence of Soviet continental Communism, enforced by the huge Russian Red Army.

Few escape petty hypocrisy when preaching the universal gospel of borderlessness. Barack Obama has caricatured the building of a wall on the U.S. southern border as nonsensical, as if borders are discriminatory and walls never work. Obama, remember, declared in his 2008 speech in Berlin that he wasn’t just an American but also a “citizen of the world.” Yet the Secret Service is currently adding five feet to the White House fence—presumably on the retrograde logic that what is inside the White House grounds is different from what is outside and that the higher the fence goes (“higher and stronger,” the Secret Service promises), the more of a deterrent it will be to would-be trespassers. If Obama’s previous wall was six feet high, the proposed 11 feet should be even better.

In 2011, open-borders advocate Antonio Villaraigosa became the first mayor in Los Angeles history to build a wall around the official mayoral residence. His un-walled neighbors objected, first, that there was no need for such a barricade and, second, that it violated a city ordinance prohibiting residential walls higher than four feet. But Villaraigosa apparently wished to emphasize the difference between his home and others (or between his home and the street itself), or was worried about security, or saw a new wall as iconic of his exalted office.

“You’re about to graduate into a complex and borderless world,” Secretary of State John Kerry recently enthused to the graduating class at Northeastern University. He didn’t sound envious, though, perhaps because Kerry himself doesn’t live in such a world. If he did, he never would have moved his 76-foot luxury yacht from Boston Harbor across the state border to Rhode Island in order to avoid $500,000 in sales taxes and assorted state and local taxes.

While elites can build walls or switch zip codes to insulate themselves, the consequences of their policies fall heavily on the nonelites who lack the money and influence to navigate around them. The contrast between the two groups—Peggy Noonan described them as the “protected” and the “unprotected”—was dramatized in the presidential campaign of Jeb Bush. When the former Florida governor called illegal immigration from Mexico “an act of love,” his candidacy was doomed. It seemed that Bush had the capital and influence to pick and choose how the consequences of his ideas fell upon himself and his family—in a way impossible for most of those living in the southwestern United States. Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg offers another case study. The multibillionaire advocates for a fluid southern border and lax immigration enforcement, but he has also stealthily spent $30 million to buy up four homes surrounding his Palo Alto estate. They form a sort of no-man’s-land defense outside his own Maginot Line fence, presumably designed against hoi polloi who might not share Zuckerberg’s taste or sense of privacy. Zuckerberg’s other estate in San Francisco is prompting neighbors’ complaints because his security team takes up all the best parking spaces. Walls and border security seem dear to the heart of the open-borders multibillionaire—when it’s his wall, his border security.

This self-serving dynamic operates beyond the individual level as well. “Sanctuary cities,” for instance, proclaim amnesty for illegal aliens within their municipal boundaries. But proud as they are of their cities’ disdain for federal immigration law, residents of these liberal jurisdictions wouldn’t approve of other cities nullifying other federal laws. What would San Franciscans say if Salt Lake City declared the Endangered Species Act null and void within its city limits, or if Carson City unilaterally suspended federal background checks and waiting periods for handgun purchases? Moreover, San Francisco and Los Angeles do believe in clearly delineated borders when it comes to their right to maintain a distinct culture, with distinct rules and customs. Their self-righteousness aside, sanctuary cities neither object to the idea of borders nor to their enforcement—only to the notion that protecting the southern U.S. border is predicated on the very same principles.

More broadly, ironies and contradictions abound in the arguments and practices of open-borders advocates. In academia, even modern historians of the ancient world, sensing the mood and direction of larger elite culture, increasingly rewrite the fall of fifth-century AD Rome, not as a disaster of barbarians pouring across the traditional fortified northern borders of the Rhine and Danube—the final limites that for centuries kept out perceived barbarism from classical civilization—but rather as “late antiquity,” an intriguing osmosis of melting borders and cross-fertilization, leading to a more diverse and dynamic intersection of cultures and ideas. Why, then, don’t they cite Vandal treatises on medicine, Visigothic aqueducts, or Hunnish advances in dome construction that contributed to this rich new culture of the sixth or seventh century AD? Because these things never existed.

Academics may now caricature borders, but key to their posturing is either an ignorance of, or an unwillingness to address, why tens of millions of people choose to cross borders in the first place, leaving their homelands, language fluency, or capital—and at great personal risk. The answer is obvious, and it has little to do with natural resources or climate: migration, as it was in Rome during the fifth century AD, or as it was in the 1960s between mainland China and Hong Kong—and is now in the case of North and South Korea—has usually been a one-way street, from the non-West to the West or its Westernized manifestations. People walk, climb, swim, and fly across borders, secure in the knowledge that boundaries mark different approaches to human experience, with one side usually perceived as more successful or inviting than the other.

Western rules that promote a greater likelihood of consensual government, personal freedom, religious tolerance, transparency, rationalism, an independent judiciary, free-market capitalism, and the protection of private property combine to offer the individual a level of prosperity, freedom, and personal security rarely enjoyed at home. As a result, most migrants make the necessary travel adjustments to go westward—especially given that Western civilization, uniquely so, has usually defined itself by culture, not race, and thus alone is willing to accept and integrate those of different races who wish to share its protocols.

Many unassimilated Muslims in the West often are confused about borders and assume that they can ignore Western jurisprudence and yet rely on it in extremis. Today’s migrant from Morocco might resent the bare arms of women in France, or the Pakistani new arrival in London might wish to follow sharia law as he knew it in Punjab. But implicit are two unmentionable constants: the migrant most certainly does not wish to return to face sharia law in Morocco or Pakistan. Second, if he had his way, institutionalizing his native culture into that of his newly adopted land, he would eventually flee the results—and once again likely go somewhere else, for the same reasons that he left home in the first place. London Muslims may say that they demand sharia law on matters of religion and sex, but such a posture assumes the unspoken condition that the English legal system remains supreme, and thus, as Muslim minorities, they will not be thrown out of Britain as religious infidels—as Christians are now expelled from the Middle East.

Even the most adamant ethnic chauvinists who want to erase the southern border assume that some sort of border is central to their own racial essence. The National Council of La Raza (“the race”; Latin, radix) is the largest lobbying body for open borders with Mexico. Yet Mexico itself supports the idea of boundaries. Mexico City may harp about alleged racism in the United States directed at its immigrants, but nothing in U.S. immigration law compares with Mexico’s 1974 revision of its “General Law of Population” and its emphasis on migrants not upsetting the racial makeup of Mexico—euphemistically expressed as preserving “the equilibrium of the national demographics.” In sum, Mexican nationals implicitly argue that borders, which unfairly keep them out of the United States, are nonetheless essential to maintaining their own pure raza.

“Migration has usually been a one-way street, from the non-West to the West or its Westernized manifestations.”

Mexico, in general, furiously opposes enforcing the U.S.–Mexican border and, in particular, the proposed Trump wall that would bar unauthorized entry into the U.S.—not on any theory of borders discourse but rather because Mexico enjoys fiscal advantages in exporting its citizens northward, whether in ensuring nearly $30 billion in remittances, creating a powerful lobby of expatriates in the U.S., or finding a safety valve for internal dissent. Note that this view does not hold when it comes to accepting northward migrations of poorer Central Americans. In early 2016, Mexico ramped up its border enforcement with Guatemala, adding more security forces, and rumors even circulated of a plan to erect occasional fences to augment the natural barriers of jungle and rivers. Apparently, Mexican officials view poorer Central Americans as quite distinct from Mexicans—and thus want to ensure that Mexico remains separate from a poorer Guatemala.

When I wrote an article titled “Do We Want Mexifornia?” for City Journal ’s Spring 2002 issue, I neither invented the word “Mexifornia” nor intended it as a pejorative. Instead, I expropriated the celebratory term from Latino activists, both in the academy and in ethnic gangs in California prisons. In Chicano studies departments, the fusion of Mexico and California was envisioned as a desirable and exciting third-way culture. Mexifornia was said to be arising within 200 to 300 miles on either side of an ossified Rio Grande border. Less clearly articulated were Mexifornia’s premises: millions of Latinos and mestizos would create a new ethnic zone, which, for some mysterious reason, would also enjoy universities, sophisticated medical services, nondiscrimination laws, equality between the sexes, modern housing, policing, jobs, commerce, and a judiciary—all of which would make Mexifornia strikingly different from what is currently found in Mexico and Central America.

When Latino youths disrupt a Donald Trump rally, they often wave Mexican flags or flash placards bearing slogans such as “Make America Mexico Again.” But note the emotional paradox: in anger at possible deportation, undocumented aliens nonsensically wave the flag of the country that they most certainly do not wish to return to, while ignoring the flag of the nation in which they adamantly wish to remain. Apparently, demonstrators wish to brand themselves with an ethnic cachet but without sacrificing the advantages that being an American resident has over being a Mexican citizen inside Mexico. If no borders existed between California and Mexico, then migrants in a few decades might head to Oregon, even as they demonstrated in Portland to “Make Oregon into California.”

Removing borders in theory, then, never seems to match expectations in fact, except in those rare occasions when nearly like societies exist side by side. No one objects to a generally open Canadian border because passage across it, numbers-wise, is roughly identical in either direction—and Canadians and Americans share a language and similar traditions and standard of living, along with a roughly identical approach to democracy, jurisprudence, law enforcement, popular culture, and economic practice. By contrast, weakening demarcated borders between diverse peoples has never appealed to the citizens of distinct nations. Take even the most vociferous opponents of a distinguishable and enforceable border, and one will observe a disconnect between what they say and do—given the universal human need to circumscribe, demarcate, and protect one’s perceived private space.

Again, the dissipation of national borders is possible only between quite similar countries, such as Canada and the U.S. or France and Belgium, or on those few occasions when a supranational state or empire can incorporate different peoples by integrating, assimilating, and intermarrying tribes of diverse religions, languages, and ethnicities into a common culture—and then, of course, protect them with distinct and defensible external borders. But aside from Rome before the fourth century AD and America of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, few societies have been able to achieve E pluribus unum. Napoleon’s transnational empire didn’t last 20 years. Britain never tried to create a holistic overseas body politic in the way that, after centuries of strife, it had forged the English-speaking United Kingdom. The Austro-Hungarian, German, Ottoman, and Russian Empires all fell apart after World War I, in a manner mimicked by the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia in the 1980s and 1990s. Rwanda and Iraq don’t reflect the meaninglessness of borders but the desire of distinct peoples to redraw colonial lines to create more logical borders to reflect current religious, ethnic, and linguistic realities. When Ronald Reagan thundered at the Brandenburg Gate, “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!” he assumed that by 1987, German-speakers on both sides of the Berlin Wall were more alike than not and in no need of a Soviet-imposed boundary inside Germany. Both sides preferred shared consensual government to Communist authoritarianism. Note that Reagan did not demand that Western nations dismantle their own borders with the Communist bloc.

“Something there is that doesn’t love a wall,” Robert Frost famously wrote, “That wants it down.” True, but the poet concedes in his “Mending Wall” that in the end, he accepts the logic of his crustier neighbor: “He says again, ‘Good fences make good neighbors.’ ” From my own experience in farming, two issues—water and boundaries—cause almost all feuds with neighbors. As I write, I’m involved in a border dispute with a new neighbor. He insists that the last row of his almond orchard should be nearer to the property line than is mine. That way, he can use more of my land as common space to turn his equipment than I will use of his land. I wish that I could afford to erect a wall between us.

The end of borders, and the accompanying uncontrolled immigration, will never become a natural condition—any more than sanctuary cities, unless forced by the federal government, will voluntarily allow out-of-state agencies to enter their city limits to deport illegal aliens, or Mexico will institutionalize free entry into its country from similarly Spanish-speaking Central American countries.

Borders are to distinct countries what fences are to neighbors: means of demarcating that something on one side is different from what lies on the other side, a reflection of the singularity of one entity in comparison with another. Borders amplify the innate human desire to own and protect property and physical space, which is impossible to do unless it is seen—and can be so understood—as distinct and separate. Clearly delineated borders and their enforcement, either by walls and fences or by security patrols, won’t go away because they go to the heart of the human condition—what jurists from Rome to the Scottish Enlightenment called meum et tuum, mine and yours. Between friends, unfenced borders enhance friendship; among the unfriendly, when fortified, they help keep the peace.

Top Photo: The ruins of a boundary fortress designed to separate Athens from Thebes; in ancient Greece, most wars broke out over territorial disputes. (HERVÉ CHAMPOLLION/AKG-IMAGES /THE IMAGE WORKS)