Americans live under an ever-growing administrative state, in which distant bureaucrats centralize legislative, executive, and judicial power. States and localities are increasingly overpowered by a growing federal government that transgresses the Constitution’s original limits. The Constitution, we’re told by the progressive-minded, is a “living, breathing” document that allows for such updating in the modern age. On the other side, originalists and textualists argue that the Constitution’s meaning is stable, that its words retain the meaning they possessed when they were written. The dispute has spanned more than a generation, and, with the recent death of Supreme Court justice Antonin Scalia and nomination of Judge Merrick Garland to the Court, has taken on tremendous political weight. Scalia’s successor, whether it’s Garland or someone else—if Republicans prevail in blocking Obama’s nominee this year—could tip the balance of the Court in favor of one of these competing interpretations. Either way, the next president will likely fill several Supreme Court vacancies and thus have the opportunity to shape constitutional law for decades to come.

Often considered the solution for—or alternative to—judicial activism, originalism has been adopted by numerous judges and debated extensively in the legal academy over the last four decades. Yet, its proponents disagree over many nuances. Some originalists look to the “original public meaning” of the Constitution, others to the meaning that it would have to a reasonable hypothetical observer. Some find a distinction between “interpretation” and “construction”; others see no difference.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Progressives cite such disagreements as proof that originalism is not a viable alternative to their preferred expansive reading of the Constitution. Yet internal debates shouldn’t obscure the guiding principles of originalism, which are surprisingly simple. Only craft and ingenuity can obscure them.

Prior to the twentieth century, most lawyers and judges interpreted legal texts, including the Constitution, by looking at the intention of a law’s authors, as evidenced by the words they used. Starting in the 1950s, the Supreme Court under Chief Justice Earl Warren began discovering rights and powers in the Constitution never previously identified. The Court created new sets of rights for criminal defendants, including the Miranda rights made famous by police procedurals on television. They instituted suppression of evidence as a remedy for unlawful police conduct. Conservatives feared that this new judicial permissiveness would exonerate many criminal defendants, against whom there was usually plenty of evidence to convict. And then, in Roe v. Wade, the Court constitutionalized the right to an abortion in accordance with what the justices labeled the “penumbras” of other constitutional rights.

The Constitution was never intended—either by those who wrote it or by those who ratified it—to have the effect given it by the Warren Court. “A constitution that is viewed as only what the judges say it is no longer is a constitution in the true sense,” said attorney general Edwin Meese in a landmark 1985 speech to the American Bar Association. Words have meaning, Meese said, and judges can discern those meanings. Judges will always have predispositions, but this can’t mean that anything goes. The Reagan administration in which he served, Meese promised, would “endeavor to resurrect the original meaning of the constitutional provisions and statutes as the only reliable guide for judgment.”

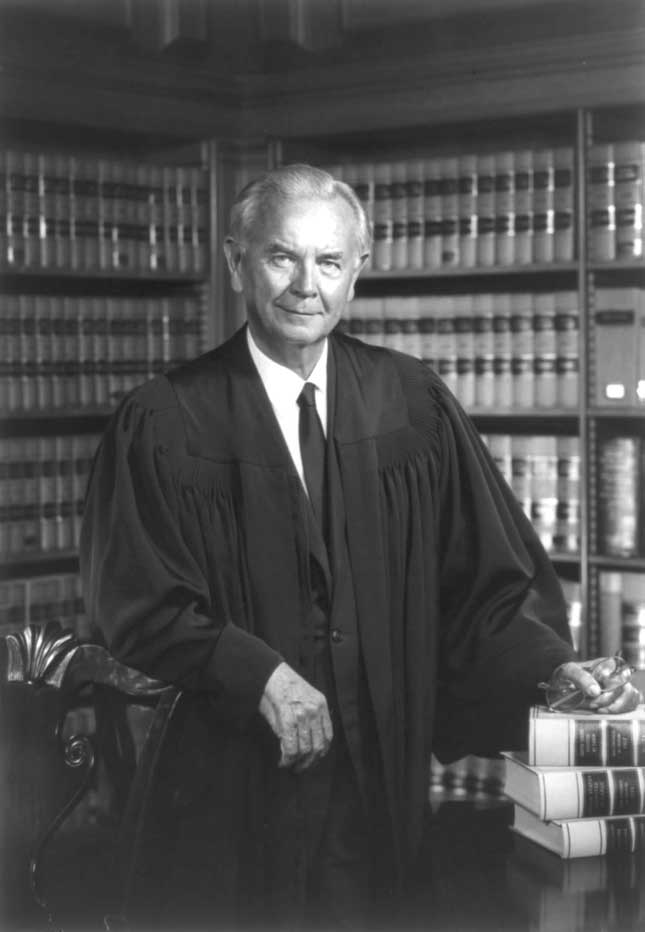

Critics of originalism pushed back. In a speech a few months later at Georgetown University, Supreme Court Justice William Brennan dismissed the judicial philosophy of original intention as arrogant and rejected the notion that modern judges could discern what the Founders thought about a particular case. “Our distance of two centuries cannot but work as a prism refracting all we perceive,” he said. “We current Justices read the Constitution in the only way that we can: as twentieth century Americans.” Law professor H. Jefferson Powell argued that the Founding generation did not intend to make its understanding of the Constitution binding for the future. Paul Brest, eventually dean of Stanford Law School, attacked originalism in his article “The Misconceived Quest for the Original Understanding,” in which he sought to undermine the idea that there is such a thing as the Founders’ collective “intent.” There were many Founders and Framers, he wrote; each presumably had his own unique intentions. Brest did, however, make concessions to what he considered more plausible versions of originalism—those that looked to high-level purposes rather than the specific intent of particular Framers and those that understood that words have meaning only in context.

Responding to these counterattacks, originalists emphasized the “original public meaning” of a constitutional provision that those who ratified the Constitution would have understood it to have. Neither the secret personal intentions of the individual Founders, nor their collective intentions, nor even the intentions of those who participated in the ratifying conventions matter under this approach. All that matters is how people understand the written words of the Constitution at the time it was adopted.

The debate continues over originalism, which is sometimes described as a theory still “working itself pure,” as Lord Mansfield once characterized the precedential evolution of common law. Originalism is not a settled theory; legal thinkers continue to refine it. Most originalists today would agree that we must first understand what the Constitution says; only then can we ask whether the Constitution, when properly understood, is legitimate and worthy of obedience.

Today’s originalists often argue that any communication, oral or written, should be interpreted by its original public meaning, unless there is some indication that it should be interpreted in another way. The original public meaning is thus the true meaning of any public communication. To maintain the integrity of the Constitution over time, Yale law professor Jack Balkin writes, “we must preserve the meaning of the words that constitute the framework . . . . If we do not attempt to preserve legal meaning over time, then we will not be following the written Constitution as our plan but instead will be following a different plan.” The content of all communication is fixed at the time of its utterance. Take the example of a letter written in the twelfth century that uses the word “deer.” As Georgetown professor Lawrence Solum has pointed out, today, “deer” refers to a four-legged mammal of the cervidae family, but in Middle English, the word “deer” meant a beast or animal of any kind. Therefore, we would wrongly read “deer” in a letter written in the Middle Ages to mean what we think of as deer today.

Or take an example from the Constitution itself. Article IV, Section Four states that America shall protect every state in the union “against domestic Violence.” The modern-day semantic meaning of the phrase “domestic violence,” Solum notes, is “intimate partner abuse,” “battering,” or “wife-beating”; it is the “physical, sexual, psychological, and economic abuse that takes place in the context of an intimate relationship, including marriage.” Yet the Framers used the term “domestic violence” to refer to insurrection or rebellion. It would be a linguistic mistake to interpret this clause of the Constitution as referring to “domestic violence” as we understand it today. “In the exposition of laws, and even of Constitutions,” James Madison wrote in an 1826 letter, “how many important errors may be produced by mere innovations in the use of words and phrases, if not controulable [sic] by a recurrence to the original and authentic meaning attached to them!” As Madison saw it, we shouldn’t let “the effect of time in changing the meaning of words and phrases’ justify ‘new constructions’ of written constitutions and laws.”

In a 1997 article, law professor Gary Lawson offered a lively justification for original public meaning when he compared reading a constitution with reading an eighteenth-century recipe for fried chicken. No one doubts that the meaning of a recipe is fixed. Because, as Lawson notes, every document is created “at a particular moment in space and time, documents ordinarily . . . speak to an audience at the time of their creation and draw their meaning from that point.” A recipe presents itself to the world as a public document. Its meaning “is its original public meaning.” Even a document with a clear original public meaning can pose problems of interpretation, of course. Some recipes, for instance, suggest adding “pepper to taste.” Such nuances, however, have to do with how, not whether, to apply original public meaning. Suppose that over the centuries, cooks began substituting rosemary for pepper in the fried-chicken recipe to suit changing tastes. According to Lawson, it wouldn’t change the recipe’s meaning. “The recipe says ‘pepper,’ and if modern cooks use rosemary instead, they are not interpreting the original recipe, but rather they are amending it—perhaps for the better, but amending it nonetheless. The term ‘pepper’ is simply not ambiguous in this respect.” A recipe’s meaning also doesn’t change over time simply because people refuse to follow it.

The same is true of a constitution, which, as Lawson explains, is but a recipe for government: “As a recipe of sorts that is clearly addressed to an external audience, the Constitution’s meaning is its original public meaning. Other approaches to interpretation are simply wrong. Interpreting the Constitution is no more difficult, and no different in principle, than interpreting a late-eighteenth-century recipe for fried chicken.” The Constitution was addressed to a public audience at a certain time, and its meaning was fixed at that time. Whether the Constitution is legitimate is an entirely separate question.

No originalist disputes that the Constitution is sometimes, like a novel, hard to interpret, and that readers might have different understandings of the text; readers at the time of the Founding did, too. Some words create ambiguity, intentionally or unintentionally. But each word still has an objective public meaning; conventional usage still limits our interpretation; and some interpretations are better than others.

Yet, a commitment to originalism doesn’t rule out the possibility of adaptation to future circumstances. Perhaps the ratifiers of the Fourteenth Amendment did not believe that the Constitution required desegregating schools, for instance, but it doesn’t follow that Brown v. Board of Education was wrongly decided. If originalists believed that only the original, expected applications of the Constitution are valid, then the First Amendment wouldn’t apply to speech on the Internet, and the Fourth Amendment’s guarantee against unreasonable searches and seizures wouldn’t apply to GPS devices. Most of the Constitution’s provisions define standards or principles—unreasonable searches and seizures, equal protection, due process—with meanings that can apply to new situations.

In Federalist 37, James Madison described both the power and the limitations of human language and the human mind, and how those limitations affect the writing and interpretation of a constitution:

All new laws, though penned with the greatest technical skill, and passed on the fullest and most mature deliberation, are considered as more or less obscure and equivocal, until their meaning be liquidated and ascertained by a series of particular discussions and adjudications. Besides the obscurity arising from the complexity of objects, and the imperfection of the human faculties, the medium through which the conceptions of men are conveyed to each other adds a fresh embarrassment. The use of words is to express ideas. Perspicuity, therefore, requires not only that the ideas should be distinctly formed, but that they should be expressed by words distinctly and exclusively appropriate to them. But no language is so copious as to supply words and phrases for every complex idea, or so correct as not to include many equivocally denoting different ideas. Hence it must happen that however accurately objects may be discriminated in themselves, and however accurately the discrimination may be considered, the definition of them may be rendered inaccurate by the inaccuracy of the terms in which it is delivered. And this unavoidable inaccuracy must be greater or less, according to the complexity and novelty of the objects defined. When the Almighty himself condescends to address mankind in their own language, his meaning, luminous as it must be, is rendered dim and doubtful by the cloudy medium through which it is communicated.

What can we take away from this remarkable passage? First, all human communication will necessarily be somewhat indeterminate—particularly when we’re dealing with a constitution that advances a new theory of government, using complex ideas for which existing words might prove insufficient. But we also learn that words express ideas, however imperfectly or obscurely—and these ideas are fixed at the time of writing or utterance. Lastly, we learn that Madison’s theory of “liquidation” is a way of resolving ambiguity. It may be that the words create some ambiguity, that the ideas expressed have uncertain applications. But over time, those ambiguities will get resolved in favor of one interpretation or another; at that point, the words can become “fixed” for future generations.

Much of what the federal government does today would not be possible under an originalist interpretation of the Constitution. Since the advent of the New Deal State, the federal government has legislated in almost all areas of life, often on the grounds that it is regulating interstate commerce. Lawmakers justify federal minimum-wage laws, labor standards, and welfare programs by invoking the Commerce Clause. The Founding generation, however, understood commerce specifically as the exchange of goods. It did not encompass, say, the manufacturing of goods within purely local dimensions. Thus, minimum-wage laws and other labor regulations should be left to the states, as should most welfare programs. Some originalists (especially the libertarian ones) also claim that as originally understood, the Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantee to each citizen of the “privileges” and “immunities” of citizenship meant that the states could not infringe on economic liberties without compelling justifications. And yet, today, most states infringe frequently on economic freedom by, for example, requiring licenses to engage in normal occupations.

Most administrative law today would have to be reversed as well. The Framers never contemplated that unelected bureaucrats would wield legislative, executive, and judicial power. The Constitution creates a specific government structure, whereby only the legislature can exercise legislative power, only the president and his officials the executive power, and only judges—appointed by the president with tenure and salary protections—the judicial power. The Constitution granted bureaucrats no authority to exercise at least two of these powers, let alone all of them at once. And yet constitutional law today allows bureaucrats to do just that.

Finally, much criminal defense law would have to be changed. Indigent defendants might not be guaranteed attorneys in non-capital cases. Police would not have to tell a suspect he has the right to remain silent. Any violation of the Fourth Amendment’s right to be free from unreasonable searches and seizures would not result in the suppression of evidence. That’s not to say that these constitutional adjustments are bad from a policy perspective, only that it is hard to justify many of them on originalist grounds. Congress could, and likely would, enact many of the criminal-procedure protections of modern Supreme Court doctrine.

Originalists have different approaches to legal precedent, however, and not all would want to go as far as undoing longstanding (if dubious) constitutional doctrines. But the important point is that originalism matters. Applied vigorously, it can transform how we interpret the Constitution and lead to a dramatic reduction in the scope and size of the federal government.

Top Photo: George Washington at the signing of the Constitution by Junius Brutus Stearns (1810-1885)