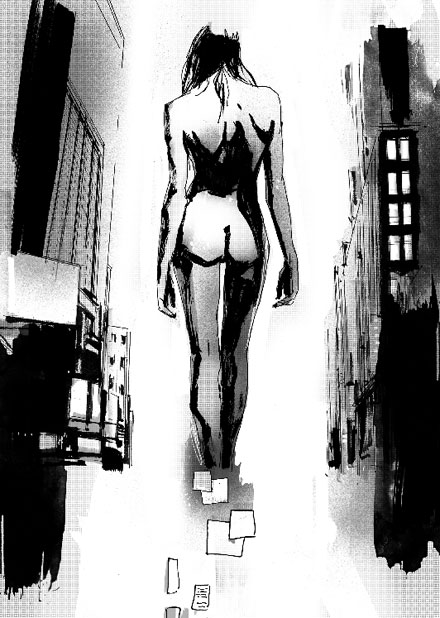

He began every day with a naked woman. FemArt.com had a new one each week. He didn’t subscribe to the site. The free 30-second sample video was enough. Explicit, even exploratory, without being overtly sexual or pornographic. Just a nude girl or sometimes two posing or laughing or running on a beach or through the grass or by a lake or near a railroad track. Not the likeliest scenarios, admittedly—he sometimes pitied the women for the harsh stones or gritty sand against their bare flesh—but their images beguiled his imagination and brought him to life.

Then there was e-mail. Notes from the Fever Swamp. Fears; conspiracies; dire predictions. I hear my upstairs neighbors whispering at night. . . . The president is one of them. . . . It’s all foretold in Revelation. . . . They have the materials they need for the Times Square attack. . . .

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Sometimes there was a personal threat as well. There was one today, in fact. We’re getting closer, Stein. You can count your days on a single hand. A single finger maybe. . . .

During his life—that’s how he thought about it: back in the old days, during his life—he had had a reputation as a hard case, a tough guy. Plenty of journalistic adventures to his credit. Government corruption exposed. Some mobster stuff. A couple of war zones. Enough danger and legal trouble and nights on the road to cost him a wife at least, a poor darling from his native suburbs who’d signed on for something a little more home-and-garden. He was no stranger to the wickedness of the world, in other words. Back in the old days, during his life.

Now though, here, alone, each time he opened an e-mail threat, his stomach did that Broken Elevator thing, that sudden, souring plunge. No point in calling the police any more. They were weary of him. Skeptical. But he—Stein—had every reason to take this stuff seriously, and he did.

He put most of the e-mails in a file labeled LUNACY. One or two—the one about the Times Square attack, for instance; plus the threat on his life—went into a smaller file labeled LEGIT.

Then he made coffee.

He drank it black, out of a mug decorated with the newspaper’s logo. Even he found that sort of pitiful. He carried the mug around the apartment, sipping from it and muttering to himself—muttering, oftentimes, phrases from his final argument with Connor, the paper’s editor in chief. Things he’d said, things he wished he’d said.

“Maybe the readers are alienated by tiptoeing, candy-assed lies, you ever think of that? . . . It isn’t about me. . . . How is the simple truth self-dramatizing? . . . Taking it personally? What does that mean? Because I’m a Jew? Is that what you’re saying? Come out and say it, you little . . .”

He hardly knew he was doing it until suddenly he’d realize. He found that sort of pitiful too.

This morning, his coffee half-done, he stopped by the window beside his desk. Lifted the slats on the shutter. Peeked out at the sidewalk three stories below: the sidewalk and the brownstones and the pale green sycamores of West 69th Street near the park. Suits and skirts on their way to work. Artists and neighborhood ladies walking their dogs. No one suspicious. No one standing strangely still, watching his window. As there sometimes was. Or as he sometimes thought there was.

He closed the slats. He never opened the shutters. Never.

Time to get to work. Time to update his blog, distilling yesterday’s research—phone calls and texts to and from a growing network of sources, websites studied through the long night just past. But before he could begin, there was a strain of music, the heavenly harp-stroke of a cartoon angel. An instant message. Rose2475.

Stein moved eagerly toward the sound. Quickly sat at his desk, his hand going to the computer mouse, his head jutting toward the monitor.

morning jerry. u there? He had made himself invisible online. She couldn’t see him. if u dont answer 1 day I’ll stop trying. Then: no I won’t. Then: really. ru there?

Im here, he typed, after a moment’s hesitation. sorry. another threat today. Hav 2 b cautious.

He despised himself the moment he sent it. Trying to make himself sound dangerous and romantic. Like a posing teen. Hoping to impress her. What a knucklehead he was. What a sucker. How did he even know she was who she pretended to be? How did he even know she was a she? Probably some old man with a fetish or some ten-year-old prankster punking him for laughs. Or one of the evildoers. An evildoer cat’s-paw, toying with him. Maybe so.

I worry about u, she wrote back, and, for all his self-reproaches, he found it crazy-gratifying: she worried about him. ur safety. ur health. ur mind even!!! y not take a break, get away, come visit me (she sed batting her lashes) meet me.

She always refused to send him photographs—and he couldn’t find any online. She said he had to come and see her for himself. She promised she wasn’t hideous. He wouldn’t look upon her and turn to stone, she said. He liked her teasing him like that, beckoning him. Little did she know he sometimes imagined her with the face and body of one of the naked women on FemArt.com. Or maybe she did know. If she was a man—an assassin smirking at the keyboard—she would know precisely the sorts of things she had maneuvered him into thinking.

Whoever she really was, he had met her first in a chat room where he was following up a tip about a cell upstate. She was a librarian in Oneida, she said. She was looking for sources of local history. That conjured in him images of a walk down tree-lined lanes, holding hands with a prim girl who would be beautiful if you would just take off those glasses, Miss Jones. . . . A little too sweet a dream. A little too easy. And all to the music of that angel chord of hers.

u could just walk out the door and hop on the thruway, she wrote. There’s zero to keep u ther. u could come today.

You can count your days on a single hand, he thought. A single finger maybe. . . .

But she was right: he could go. He could see her for himself. Stuff a change of clothes into a traveling bag. Be there by afternoon.

how ru? he wrote back. Wuz new in oneida?

She told him. same old. Getting ready for the library’s summer programs. Reading books to the children at story time, her favorite part of the day. My ordinary life.

Stein touched the monitor with his fingertips.

After Rose2475 signed off, he settled down to work.

His computer screen was divided into windows. His blog, The Threat Level, was at the center. His new documents and interviews were in tabbed folders to the upper right, his saved research in folders to the left. Live views from various webcams around the city were arrayed along the bottom: shifting angles on Times Square, Central Park, Ground Zero, the Manhattan skyline. Up top, there were shots from the security camera outside his brownstone and from the camera he’d mounted above his own apartment door to take in the welcome mat, the landing, and the top of the stairs.

There were divisions within the Threat Level page as well. Links to other blogs. Relevant news stories from other sources. His own most recent posting. And—always—the column that had gotten him fired: “Their God Is Not God.” He never took that down. He left the headline boldly visible—and the lede as well: “If God is real, some descriptions of him will necessarily be more accurate than others.” Then a link to the body of the text. It made him feel good—made him feel unbowed and defiant—to keep it posted like that. He couldn’t be silenced, etc. Connor and his compliant city room could all go to hell, etc. But, of course, he knew how little it meant in fact. Even as it swirled down the drain with the rest of the lying old media, the newspaper maintained a circulation of half a million. His blog? It had maybe 300 subscribers, got maybe a thousand hits on a good day. A voice in the blogosphere wilderness. A voice crying: Their God is not God.

Never mind. Business time. He went at the keyboard. Intel pointing to an imminent and catastrophic attack on Times Square seemed increasingly credible. The mosque the city was planning to build near Ground Zero was widely viewed as a major victory among the terrorist cells and had inspired them to plan more missions. Federal denials of increasing cell-phone and Internet chatter were the result of bureaucratic stupidity and politically correct appeasement. Don’t be offensive. Don’t get them angry. We don’t want to insult anyone’s religion. The same logic that had lost Stein his job.

“Why the hell not, Connor?” he muttered. Law enforcement sources say their hands have been increasingly tied, he wrote. “You think slapping God’s name on something makes it sacred?” The cells have used so-called community liaisons to infiltrate antiterrorist agencies at the highest level. “I could slap God’s name on a butcher knife and cut your stupid throat, you pompous, cowardly . . .”

Once he got going like this, the prose flowed, febrile and fluid. On and on without paragraphs or punctuation, just the occasional ellipsis like a gasp for air. Even he—some part of him—watched the words unwind and wondered if he was raving now, if he was mad. But the sources were reliable, deep, solid. He was still a good reporter. He leaned into it and went on and on.

There was—suddenly it seemed—a knock at the door. He nearly jumped out of his own skin. That wasn’t just a turn of phrase either. He really felt his inner man skyrocket while his body froze in place.

“Who is it?” he shouted, turning in his chair only slowly.

“Morton’s. Your sandwich,” a voice came back.

He glanced at the clock on the bottom of his screen. Noon already. He checked the view of the camera above his door. It was the guy—one of the usual delivery guys. No one else, as far as he could see.

He felt the stiffness in his body as he stood. He went—not to the door—but to the shuttered window on the opposite wall. “You didn’t buzz,” he shouted over his shoulder. “How’d you get in the building?”

“Old lady was coming in at the same time, let me in.”

Stein peeked out through the shutter slats. There. On the sidewalk. A man—an olive-skinned man in jeans and a T-shirt—just now turning away. Wasn’t he? Just now walking away? Or had he simply been strolling past?

Stein closed the slats. Swallowed hard. Went to the door. He didn’t use the peephole. They could just blow you away through the peephole. He opened the door only enough to let the delivery guy pass the paper bag through to him. He passed back a cash tip.

Delivery Guy shook his head. “It ain’t a jungle outpost, man. You’re in the middle of Manhattan.”

“What difference does that make if nobody’s looking?”

He shut the door.

He set the bag by his keyboard. Took up the phone, the land line. There was usually only one other person in the building at this hour. Agnes Reese. Eighty-something. Half-crazy and all alone, just her and her long-suffering bichon. He could hear her phone ringing downstairs from here. He could hear her heels on her wooden floor.

“Yes?” she said tentatively. No one ever called her but con men, politicians, and her son in St. Louis.

“Agnes. It’s Jerry, upstairs. Did you just come home, let the delivery man in?”

“I don’t think so,” she said slowly. “No. No. I don’t think so. I’ve been home all morning.”

He felt the cold sweat come out on his face. Probably nothing, he thought. Then he thought: Famous last words. What he’d be saying to himself just before they came through the door: Probably nothing. Then: Bang.

He tried to shake it off. He’d been under fire before. He’d been closer to death before. Still. There was something peculiarly awful about the prospect of dying in silence, dying invisible, as if you had never existed, right here at the heart of the city. Unrelated to terrorism, the police would say. Because that’s what they always said now, when they could get away with it. And the reporters, even his former colleagues at the paper, maybe especially them, would nod and say, Strange dude, you know. A blog like his attracts a lot of wack jobs.

If a man tries to tell the truth and there’s no one willing to hear him, does he make a sound when he falls?

He cut a sad figure even to himself as he sat eating his sandwich, mashing the meat and bread mechanically, tasting nothing. But he was roused from self-pity by that lone, comically angelic chord.

lunchtime here. been thinking about u. r u ok?

Rose2475.

Again, he hesitated, one hand above the keyboard. Then he pecked out. dunno. onto something with this times square thing. lotso threats.

o jerry. u have to stop. get out awile. ull make yerself crazy. the life of the world is not on your shoulders.

who says? wot if it is?

u still have 2 live. ull make yourself crazy. cmere. really. u need someone 2 talk 2. me 2. need perspective. zero is ever as bad as it seems.

“Except when it is,” he murmured aloud.

When she was gone, he sat with his sandwich in his hand half-eaten, his soda on the desk half-drunk, and he stared at the webcam images of the city. He turned the sound up on a live video of a Times Square corner. Heard the traffic noise there like the ocean in a seashell. Saw a workman with a dolly maneuvering the curb. Tourists passing in girl-boy pairs. A woman in her spring dress who drew from him the same life-longing as the nudes at FemArt.com. Cmere.

On other windows, there were other scenes. Small billowing spring clouds passing behind the spire of the Empire State Building. The ruin of Ground Zero, digger-trucks pawing at the dust of the murdered dead. A businessman in Central Park, strolling—dreaming—with his hands in the pockets of his suit. The skyline from across the East River, a barge passing lazily on the water.

He didn’t break down and cry for his city. He wasn’t the type. But he felt the urge. His eyes moved from one window on his monitor to another and another until he could almost feel the texture of the air out there, the concrete under his shoes and the towers of steel and glass bending over him like a worried mother. He could almost—almost—lift his eyes to the strip of bright blue sky above the building tops, clear as a portal through which holy heaven could savor the striving stone prayer of the place, of man in his free and civilized moment, the living Manhattan.

He had been asking himself, it seemed, forever: Was he insane, or was he alone in seeing the world as it was? It hadn’t occurred to him until this second that he might be both.

Now, he felt, he was about to come to a decision. Like a hero in a movie when the music swells. He was about to stand triumphantly out of his chair and stride into the bedroom and throw some clothing into a bag and go, just go.

Talk about self-dramatizing, he told himself. How courageous did you have to be to steal an afternoon with a librarian in Oneida?

And he really was about to—he told himself—he really was, when a swift and sudden shadow passed through a webcam window and was gone.

His eyes moved to the spot. The shot from the security camera outside the brownstone. It was mounted high and pointed down at the door to the vestibule. There was no one there now, no one visible. But he’d seen—he thought he’d seen—something—the movement of the door, maybe, as it opened and closed. He thought he’d caught it from the corner of his eye as he gazed at the shifting views of the greater city.

And now—now he heard something too. The creak of a tread on the brownstone staircase. A knock—not on his door but on Agnes Reese’s door downstairs. So there, it was one of her deliveries or a workman the super had sent, that’s all. Yet Stein sat very still, and listened. He heard Agnes’s heels on the wooden floor. Heard the door open. Her quaking voice, muffled and low. A man’s voice answering. The door closed again. Then silence.

Slowly, Stein lay his sandwich down on the wax paper by his soda cup. Why didn’t he hear her footsteps, her heels on the wooden floor retreating? Why didn’t he hear the tread creak on the staircase as the man went away?

Probably nothing.

His palm went over his clammy face and he despaired.

He was unsteady when he stood. Unsteady when he moved to the window again and peeked out again through the slats. He saw a man sitting on the stoop across the street. Wasn’t it the selfsame olive-skinned man as before? The same man who had quickly turned and walked away before? Now he was just sitting there, just biding his time.

Stein stepped decisively to the phone. Dialed Agnes Reese again. He heard the phone ringing downstairs. Ringing and ringing. No footsteps. No one answered. It took him three tries to fit the handset back into its cradle.

Vertigo. The Broken Elevator. His mind blank. He drifted back toward his desk, unthinking. Unthinking, he gazed at the webcam windows. The view of Times Square was a broad one now, taken from several stories above the street. A river of vans and cars and yellow cabs moving down Seventh. A tide of people walking on the sidewalks and the pedestrian lane. A ceaseless dazzle of advertising imagery flashing above it all on video screens as big as houses. One soaring billboard of a beauty in a bikini presiding over the street like its sovereign goddess.

Stein stared at the scene. Shifted his eyes and stared at Ground Zero, the digger-trucks pawing the dust.

Their women wore black cowls like Death.

When he moved again, he could not tell whether his sudden energy was courage or terror. He broke from the spot and dashed for the bedroom door. He did what he had meant to do: threw a bag on the bed, threw clothes into the bag. But now he could not tell—he really could not determine—whether he was planning to make his heroic march into the unknown or his getaway in cowardly panic. What was the difference? How could you know? A man walks a tightrope with his eyes closed. Is he a gallant daredevil, or just afraid to look down? Likewise a man who goes about the business of life for another day, knowing.

He carried his bag to the door. He glanced back at the computer, at the windows showing Ground Zero, Times Square. He heard the ocean-in-a-seashell traffic. He heard a tread creak on the staircase.

He stood there, his hand on the doorknob.