They say it’s inadvisable to meet your heroes. But take it from me: sometimes it works out. This is the story of one of those times.

In the late 1980s, as an undergraduate at Berkeley, my best friend somehow made the acquaintance of a much older lady—she was over 40, so ancient to us—and spent a great deal of time with her. A similar ethnic and geographic background (Korean, mid-Wilshire Los Angeles) and a shared affinity for classical music brought them together. Berkeley can be a difficult place to adjust to, wherever you come from. Coming from a strict and religious Korean household—even one in California—is about as alien as it gets. Eddie’s lady mentor worked for the university and had lived in Berkeley for years, so she was a source not just of solace but of advice for him.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

One day, Eddie invited me to come along with him to meet his friend and her boyfriend at Café Milano on Telegraph Avenue—the same place where Dustin Hoffman, in The Graduate, slyly sat sipping cappuccino, waiting to intercept Katherine Ross and make it look like happenstance. I don’t remember the details of my own little coffee klatch all that clearly. But I do remember being shocked by the vitriolic anti-American, anti-white rhetoric of the boyfriend, who claimed to have once been a Black Panther.

Somehow, despite growing up in Northern California and having a criminal prosecutor for a mother, I did not really know what a Black Panther was. Innocent times! So I headed to the library stacks and looked them up.

And found Radical Chic, by Tom Wolfe. Some years prior, a friend of my parents had given me a subscription to Rolling Stone. All throughout my high school years, Rolling Stone published, serially, some story about some campfire or something by some guy named Wolfe. It was teased on the cover of every issue. I never read a single installment, but seeing Wolfe’s name repeatedly fixed it in my head. So when I saw it again on that little book about the Panthers, I experienced what Wolfe himself once termed “The Shockkkkk of Recognition.”

I took Radical Chic back to my little flat off Telegraph, not knowing what to expect. To say that I was blown away would be an understatement. Reading Wolfe for the first time is like your first taste of ice cream, but much better. Actually, it’s like a combination of ice cream, champagne, laughing gas, and the most intellectually satisfying brain teaser you’ve ever solved. Or it’s like a roller coaster that goes faster and higher, has more unexpected twists and turns, and is more fun than any you’ve ever ridden. And when it’s over, you get out of the car not just exhilarated but smarter. The experience is so joyously jarring, you know that your life just changed forever. Certainly mine did.

From that point on, Tom Wolfe became a constant companion—his books always within reach, his thoughts deeply influencing my own, his many hundreds of quotable quips at the ready when I need them to make sense of some absurdity.

I read Radical Chic in one sitting, laughing so hard that I was sure I must have missed a great deal. So I read it again. And again. Then I started pacing around my apartment, reading it aloud to my roommates, stopping to repeat certain passages with the admonition “Listen to this! Listen! Are you listening?” all the while doubling over with laughter.

Before long, I had to return the book to the library. But one of the glories of Berkeley is its abundance of well-stocked, well-priced used bookstores. I easily found not just Radical Chic but all of Wolfe’s books, which I began to comb methodically through.

One of the things that hooked me on Wolfe was that so much of what he wrote about was familiar. Though a Southerner by birth and a New Yorker by choice, he was fascinated by California and wrote a great deal about my home state. The same way that, when you see a movie scene shot in your hometown certain synapses fire, my eyes would widen—hey, I know that place!—reading Wolfe describe San Francisco or Berkeley or Santa Cruz or Los Angeles or the 101. It’s the same appeal that often brings me back to Steinbeck and Hammett and Chandler—familiarity, but also the hope that the greatness of a great writer somehow ennobles the setting, and perhaps by extension we mere inhabitants.

Another hook was New York, which I first visited when I was seven but which grabbed me on my return at 13. I knew I had to live there someday. Until then, I would study it like a biologist examining the genome. In this sense, Radical Chic was my perfect introduction to Wolfe: as much about New York society, high and low—about which I knew little but wanted to know everything—as it was about familiar, taken-for-granted Oakland.

But I quickly add: Radical Chic is the perfect introduction to Wolfe for anyone. First, because it’s short. Wolfe’s ambitions enlarged with success and his books grew progressively longer, until a final return to brevity. Not to disparage his long books, but long can frighten readers, while short attracts them. Radical Chic was originally published as a magazine article that, like John Hersey’s monumental Hiroshima, gobbled up an entire print run. Second, the book hits so many of Wolfe’s core themes: New York, status, money, urbanism, America, race, intellectual posturing. Third, it is the purest distillation of Wolfe’s signature style, Wolfe at his Wolfiest. It became commonplace later in Wolfe’s career for even friendly reviewers to profess fatigue with his style. Some even went so far as to allege that the pyrotechnics hadn’t merely become shopworn, but that they had never really worked. Radical Chic grinds that charge to dust. Every paragraph, every sentence, every word, every punctuation mark—traditional or improv—is exactly as it should be.

A bit later in my college career, a crazy, malevolent professor (not at Berkeley, though he would have fit right in) in one of those departments that should not exist gave a speech in which he vented his anti-Semitic spleen. I don’t know if it was because his name happened to be Leonard or what, but into my brain bubbled up the contrast between this Jew-hating black Lenny and the Jewish Lenny of Radical Chic, gamely welcoming the Black Panthers into his 13-room Park Avenue duplex to help them raise money for a revolution that, had it come, would have slaughtered him and his entire family. So I wrote, for our right-wing campus agitation paper, a little piece called “A Tale of Two Lennies.” I wrote it in self-conscious mimicry of Wolfe’s style. Like most imitations, it is a pallid copy of the original. Still, in my youthful exuberance, I was proud of it.

One of the things that starstruck young people do is write fan letters. So I wrote one to Wolfe, clipped and included the piece, and sent it off. (His address, then as later, was surprisingly easy to discover.) Weeks, then months, went by with no response. Ah, well. He’s a busy man and surely gets a ton of fan mail. Imagine my surprise one day when in my mailbox appears an envelope from some place called “The Breakers” in Palm Beach. Having at that time never been to Florida, I hadn’t even heard of it. Apparently it was a hotel—the one where Tom Wolfe happened to be staying when he answered my letter.

He loved my piece—called it “priceless”—thanked me for sending it, encouraged me to keep writing, and concluded with one of those boffo signatures that look like Las Vegas casino signs. That piece of paper remains one of my prize possessions. I sent Mr. Wolfe two or three (maybe four) more letters over the years. (I always called him “Mr. Wolfe,” in person and in correspondence. He had that effect on you: courteous to a fault, but always formal.) He didn’t always answer, but he mostly did, and each response is a gem. I don’t know if that’s because he took the same care writing private letters to strangers as he did in crafting his published works or if he was just that good. Probably both.

One more tidbit from my college years. At the beginning of my final semester, I discovered that I didn’t have quite enough units to graduate, or hadn’t fulfilled some requirement, or something; I forget the details. I had to scramble to find some course that would check the right boxes. I found one called “The Social Psychology of Clothing.” And, while the subject sounds trivial, or at least unworthy of academic study, I confess that I enjoyed the class. I had some years prior developed a serious interest in clothes. This, needless say, further cemented my interest in Wolfe, arguably the greatest clotheshorse of the twentieth century, and unquestionably clothing’s deepest analyst. For our final project in the class, we were tasked with analyzing the clothing in a movie of our choice. I had what Wolfe liked to describe as an “Aha! moment.” My project would focus not on a movie, but a book: The Bonfire of the Vanities, by Tom Wolfe.

Bonfire turned me from a Wolfe fan into an idolater. Some months after I discovered his work, my parents brought me with them to England. The pound cost two bucks at the time, so the trip was a bit painful for them, but I had a blast. I brought Bonfire with me—the last Wolfe book I had yet to read—and, finding it difficult to sleep that first time-out-of-joint night, I picked it up, hoping that I would drift off. But I had by this time enough experience with Wolfe that I should have known better. I could not put the book down and kept reading until my parents woke up in the morning and berated me for not having slept. I never did adjust to Greenwich Mean Time on that trip.

But I did read—twice through—Tom Wolfe’s masterpiece. Yes, I will stand with conventional wisdom here in agreeing that Bonfire is Wolfe’s best and most important book. That’s not to sell short his subsequent work, about which more below. I am not in the camp which holds that Wolfe peaked in 1987, that A Man in Full is an ambitious failure, that I Am Charlotte Simmons and Back to Blood are failures simply. They have real, underappreciated strengths.

But Bonfire accomplishes every task Wolfe set for it, which were many. The portrait of New York City is both time-bound and timeless. It captures the filth, menace, and mayhem of pre-Giuliani New York like a Scorsese movie shot on location. But so much of what Wolfe describes—caste stratification, the dominance of finance, real estate obsession—endures, part of the city’s DNA. Even the glorious restaurant set-piece, at the immortal La Bou d’Argent (a whole essay could be written about Wolfe’s hilarious fictional proper names), could easily be imagined today, despite massive changes to the New York food scene since 1987. Bonfire remains the decoder key to understanding New York.

And the prescience is striking. It’s such an old saw to praise Wolfe’s predictive powers—“God plagiarizes Tom Wolfe,” David Brooks once quipped—and yet . . . it still must be said. Foresight is the supreme virtue of the statesman, proclaims Thucydides. Tom Wolfe had foresight to burn, almost a crystal ball. Would he have made a great statesman? Be that as it may, it does feel sometimes as if the plot of Bonfire is being acted out in real life over and over, with—variously—Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, and Freddie Gray filling in for Henry Lamb, while Mike Nifong and Marilyn Mosby graciously step up to take on the role of Abe Weiss.

Perhaps America’s leading judge who never made it to the Supremes, Richard Posner—a prolific writer on topics well beyond the law—initially dissed Bonfire but then as the years went by, realized he had been wrong and published a mea culpa:

When I first read The Bonfire of the Vanities . . . it just didn’t strike me as the sort of book that has anything interesting to say about the law or any other institution . . . I now consider that estimate of the book ungenerous and unperceptive. The Bonfire of the Vanities has turned out to be a book that I think about a lot, in part because it describes with such vividness what Wolfe with prophetic insight (the sort of thing we attribute to Kafka) identified as emerging problems of the American legal system . . . American legal justice today seems often to be found at a bizarre intersection of race, money, and violence, an intersection nowhere better depicted than in The Bonfire of the Vanities even though the book was written before the intersection had come into view.

Not that I understood any of this on those first two reads. I was more interested in all the specific details about New York—and the clothes. Oh, yes, Wolfe talks a lot about clothes in that book. In fact, he does in most of his books. This really irritates a certain class of reviewer. One objection may be taken as representative:

That the bailiffs almost gave their bauble [that is, the National Book Critics Circle Award] to Tom Wolfe’s catalogue of shoes—electric blue lizard pumps! snow-white Reeboks! bench-made half-brogued English New & Lingwoods!—is scary.

The criticism here is facile: Wolfe should not mention any of this because it doesn’t matter, and the fact that he mentions it is proof of his shallowness.

But this fundamentally misunderstands what Wolfe is doing. The inclusion of such “status details” is one of the four core literary devices that distinguishes New Journalism from Old. Wolfe got it from the novelists—Balzac and Zola, especially—and kept at it when he, too, embarked on fiction. Not just the characters themselves but their relations with and to one another are more fully realized through the inclusion of such details. They help the reader understand the “statusphere” (another Wolfean coinage) in which the characters live and move. An added benefit is, if you’re into clothes—which admittedly not everyone is—these details are just fun.

So back to that last semester. I relayed my idea to the professor, who at first seemed shocked that any student would volunteer to give up the ease of film for the relative difficulty of print. But she assented. Years later, I told Mr. Wolfe about this and he expressed interest in seeing the paper. I searched in old musty boxes but couldn’t find it.

Within two years, I had made it to New York. I felt exactly as Wolfe described his first sight of the New York Herald Tribune newsroom in 1962. Well . . . all right! This must be the place!

Strolling Fifth Avenue one Sunday, I saw in the window of a bookstore—back then, bookstores could still afford Fifth Avenue—the unmistakable dustjacket of The Bonfire of the Vanities, but with the enticing words “With a New Foreword by the Author.” I had to have it. What a fresh thrill reading that foreword was! This was Wolfe’s second declaration of war on the novelists (the first was his bravura introduction to The New Journalism anthology). He triple-dog-dared aspiring scribes to leave the house, do real reporting, and write realistic fiction. I knew in my bones that he was speaking directly to me. I there highly resolved to write a realistic novel about Berkeley. I began thinking of a plot. This led my poor little brain into all sorts of cul-de-sacs and dead ends. Making stuff up is harder than it looks. Especially if you want the whole thing to be eminently plausible, which is one of the great strengths of Bonfire’s plot.

So I had another Aha! moment and decided to analyze the plot of that novel. In my little apartment on East 50th Street, I reread it again, taking notes on all the scenes and their sequencing. I mapped out the plot on sheets of printer paper that I laid out on the floor in a complex matrix of timeline, characters, and places. Lo and behold, I concluded that Bonfire’s plot is perfect, like the innards of a Swiss watch.

Those who criticize the ending don’t get it. No, it’s not a whiz-bang conflagration. But it’s what would happen—indeed, it is what has happened in so many similar circumstances. The pitch-perfect New York Times parody that concludes the book could not be improved upon by Swift himself.

I never did finish my Berkeley novel, I think for two fundamental reasons. First, I had to write it all from memory because I was never able to get back to Berkeley and do any real reporting. Second, because—as I sinkingly discovered—I’m just not that good. I am 99 percent sure I would have been a lousy reporter, my plot never came together, and the writing style was too faux-Wolfe, a Canal Street knock-off.

In New York, I worked for the Manhattan Institute for a year. Institute vice president Vanessa Mendoza likes to say that the people who work there either stay one year or their whole lives. There are a lot of us one-year alums floating around out there, former kids to whom the Institute gave their start. One of the great things about working there was that the leadership allowed—no, encouraged—the young people to go to all the events. So there I was for my first Manhattan Institute lunch at the Harvard Club on West 44th Street, a glorious McKim Mead & White pile that is exactly the kind of building that non-New Yorkers who love New York think of when we think of New York.

And there he was—no doubt about it—resplendent in white, sitting at the head table next to the police commissioner. The lunch duly broke up as most scrambled off, back to work, while a few milled around chatting. Tom Wolfe remained, momentarily alone. Here was my chance. And what did I do? Did I approach him and thank him for sending me that first letter? Alas, no: I chickened out. He got out of there without having been entreated by an annoying fan.

Before long I was in Southern California, in graduate school, not (yet) having given up on my Berkeley novel, nor my ambition to be the West Coast Wolfe. In fact, I started telling people “I want to be the West Coast Tom Wolfe.” I studied California with great care (to the neglect of all those required courses I didn’t like; I did keep up with my concentration, though). So much (in Wolfean terms) “material” to one day sink my teeth into!

I even got a white suit. Well, not exactly. I got a linen suit in the lightest tan I could find. Cream linen is a traditional getup for warm climes, you see, and a totally different thing than white wool, which would have just been blatant copy-catting, which I was above. That suit didn’t get out much but it did prove useful on occasion. Halloweens, for instance. (Getting dressed up for Halloween past age eleven may seem preposterous until you reflect that the objective shifts from candy to girls.) I bought a wide-brimmed straw hat, added my white bucks, and voila—I went as Tom Wolfe.

Somehow, I got involved with a band trying to make it on the Sunset Strip. Here was a chance to do real reporting. I started hanging around their rehearsals, listening, asking questions, taking notes, weeks of this. Wolfe once explained his white suits as “anti-camouflage”; that is, he was making no pretense to being on the same wavelength as his subjects. He was the “man from Mars,” there to observe the mysterious natives. The more he stood out and apart, the more they wanted to explain patiently to this out-of-touch square what they were all about. So I wore the white suit to many of those rehearsals, and to all of the band’s performances. It worked. I got a lot of juicy material—which I never did anything with.

The wait for Wolfe’s next big book was excruciating. I thought often of Allan Bloom’s remark about nineteenth-century Wagnerites impatiently waiting years for the great man to finish his next “music drama.” Painful—but on the other hand: what a time to be alive!

Sometime along the way Wolfe published a discarded excerpt, “Ambush at Fort Bragg,” in Rolling Stone. I devoured it. It was not up to his best, but it was the first fresh taste of Wolfe since Bonfire, and it was filled with many of the things we expect and love from him: inside looks at closed statuspheres (network news, elite military units), skewering of elite pretentions, and the stone-cold courage to report exactly what he sees (maybe unit cohesion is undermined by social experimentation?).

Soon Rolling Stone would publish excerpts of the Big One, the next novel. In my case, this was casting a half-filled vial before a junkie. On Friday, November 13, 1998, on my lunch hour, I left my office in the California State Capitol building (where I was working as a speechwriter for Governor Pete Wilson) for a bookstore on K Street. The New York Times had mistakenly reported that A Man in Full would be available the prior Monday. But no store in town (I called them all) would sell it to me, despite, apparently, having crates of copies in the storeroom. The publisher’s instructions, they said, were strict: Friday! I called the publisher in New York just to be sure, and sure enough: Friday!

Friday at last arrived. There was no great Wolfe display, no stacks of his new book, in that K Street window. How could that be? I asked a clerk. “Oh, that’s not released yet,” he said.

“Yes, it is,” I insisted. “Today’s the day.”

“No, it’s next week I think,” he said, walking away.

“No!” I almost shouted. “It’s today! I called the publisher! They said it’s today!”

He spun around to look at me, perhaps to evaluate if security would need to be summoned. I must have looked harmless enough because he just said “OK, let me check,” and went over to a computer, typed some words, and the green phosphorescent screen produced the answer I craved. “Hey, thanks for telling me, man. I guess we better get those unpacked!”

“Never mind that now, can you just get me one? Please!”

I am not sure how I got through the rest of the workday. I do remember watching the clock wide-eyed, like a schoolboy waiting for the final bell before summer vacation. I left the office promptly at five o’clock to the second and raced home to our little Craftsman bungalow in Curtis Park. I told my wife “I am not to be disturbed for the next 48 hours at least.” I lit a fire, sank into the couch and read A Man in Full, stopping only to nap when absolutely necessary.

A Man in Full is Tom Wolfe’s biggest and most ambitious book, even if it is not his best. In it, he tries to do much more than he had done in Bonfire, and he mostly succeeds. The book demolishes any notion that Wolfe is a cynic with no awareness of or regard for a higher life, for the soul. Where he stumbles is plot. I do not believe, as some others have asserted, that the reason is because he simply cannot plot. Bonfire proved that he can, as would his later work. No, what got him that time was I think the sheer scope of his ambition. He tried to do too much, to update the Iliad and the Odyssey and the Aeneid, with more than a little Epictetus thrown in, forgetting that successful epics are ruthlessly selective. They invariably begin, and end, in media res.

I read every interview Wolfe gave about the writing of that book, and there were many. He seemed to feel that he needed to explain or apologize for having taken so long. To appreciate Wolfe’s astounding ambition for A Man in Full, one must recognize that, big as it is, Wolfe left out a ton. Not just “Ambush at Fort Bragg,” but subplots on Japan, the art world, California Sikhs, and much else—all of which he had already studied up close and at length. The temptation to jam it all in there, somehow—to give in to what economists call the “sunk cost fallacy”—must have been immense. But he resisted, mostly.

To understand Wolfe’s perfectionism, consider this. Originally, the character of Ray Peepgas was to live in New York. Wolfe wrote him that way for years, with the whole banking subplot set in Manhattan. But the more time he spent in Atlanta, the more he regretted this choice. One day, five or six years into the writing of the book, at lunch with his editor, he offhandedly mentioned this misgiving. The editor suggested moving the action south. It was the answer Wolfe did, and did not, want to hear. On the one hand, taking New York out of the picture, to focus more on the core setting, would make for a better book. On the other hand—lost time.

Wolfe had been here before. Sherman McCoy was originally a writer. That later struck Wolfe as a cop-out and missed opportunity. So he reimagined Sherman as a bond salesman. Making that work took another two years of reporting and rewriting, but the result was worth it. As time slipped away, the pressure increased—not just on Wolfe’s pride but also on his finances. Wolfe occasionally dropped hints about this, without going into much detail. But one gathers that he had to borrow a lot of money in the 1990s to keep his bigtime lifestyle going (one is reminded of Churchill). A blockbuster Man in Full was therefore necessary to save not just his reputation—had he peaked and crashed?—but his very hide. He had but one hand to play, and with it he had to clean out the table.

Which he did. I don’t mean to leave out Wolfe’s intervening heart attack, quadruple bypass, and ensuing black-dog depression. But I do not buy the assertion that this episode explains A Man in Full’s plot problems. (And, to be clear, the problems are only with the plot. By every other English 101 metric—character, setting, conflict, theme, symbol, point of view, style—the book is a masterpiece.) I think that, in trying to do so much, he simply wrote himself into corners. Indeed, he told me as much.

Years later, in restudying A Man in Full, I concocted a complex hypothesis to explain the earthquake that springs Conrad Hensley from the Alameda County jail. This included recourse to the Greek concept commonly expressed in Latin as deus ex machina, which I connected to Conrad’s emerging Stoicism. I once had occasion to explain my hypothesis to Mr. Wolfe and asked him, proud of my cleverness, if I had gotten it right. He replied, softly, almost apologetically and perhaps a little embarrassed, “I had to get him out of there.”

After A Man in Full, I became something of part-time magazine writer. I reviewed all of Wolfe’s books. There weren’t many. He never again took 11 years to write just one, but neither did he become fast. I had not, at least not in my head, given up on my Berkeley book. But I hadn’t worked on it much, either. Part of me dreamed of, someday, taking a big block of time, squatting in my parents’ pied-a-terre on King Street, in San Francisco, and riding BART to Berkeley every day and seeing what was up. Not that this was ever a serious possibility. But when Wolfe announced his next big book would be about the university, I mentally gave up. He’s going to do it, so why should I bother? It would have been like some hack trying to paint The Night Watch after Rembrandt had already gotten the commission.

When I Am Charlotte Simmons dropped in 2004, I read it greedily, as I always did any new Wolfe. I reviewed it, too, and committed the cardinal sin of a book reviewer: reviewing not the book I read, but the book I had wished it would be. My book was going to be all about political correctness, leftist persecution and intellectual stagnation, faculty pettiness, administration fecklessness, student mau-mauing, and so on. Wolfe’s, palpably, was not. I didn’t get it and was disappointed. But eventually, like Judge Posner, I would correct the record.

Once I accepted the fact that the bigtime had eluded me forever, I began to focus on smaller, realizable projects. California was, and remains, a primary focus. In the course of studying the old homestead, it dawned on me that the West Coast already had its Tom Wolfe, and his name was Tom Wolfe. So I pitched an article on Wolfe’s voluminous California writings to the editor of this magazine. When he said yes, I asked Mr. Wolfe for an interview.

Now, Tom Wolfe was a strange combination of very public and somewhat elusive. No Salinger or Pynchon he, Wolfe delighted in giving interviews, explaining himself, making public appearances, and being a man-about-town. But reaching him to request that interview—that was not so easy: he answered letters, but not all of them, and he was much more likely to respond to a request for information than for any kind of physical commitment. I heard stories about outfits wishing to offer him lucrative speaking gigs and not hearing back for months, if at all. Of course, he was solicited to write for every magazine under the sun, but—I am told—rarely responded. If he had something to say, he would say it—and then send a finished piece to an unsuspecting editor. Would he be interested in this little thing Tom Wolfe happened to toss off in his spare time? Are you kidding?

To people outside his immediate circle, Wolfe communicated by fax, long after this technology had been obsolesced, but then what would one expect from a writer who typed on a manual Underwood to the last? The fax number itself was a secret closely guarded by those who had it. I managed to get it.

I hauled my ancient fax machine down from the attic and hooked it up. I sent Mr. Wolfe a fax outlining my intended article and what I wanted to talk to him about. Many days went by but eventually the old machine beeped and burbled. Tom Wolfe would be delighted!

The appointed day—Thursday, August 2, 2012—remains fixed in my memory like the North Star. I was to arrive at his apartment at 11 a.m.—which I did, after putting in a cursory two hours in the office. (I had long been back in New York, working various corporate gigs.) Wolfe lived in high style, I must say—right next to Michael Bloomberg’s townhouse, in the same building as the CEO of a firm for which I would later work. Except that Wolfe lived on the floor above. (Like Sherman McCoy, he occupied one of those grand full-floor spreads where each elevator stop is for just one apartment.) I marveled at the tastefulness of the décor and the vast collection of books ranging over every subject: fiction, criticism, philosophy, psychology, neuroscience, art, architecture, history, urbanism, and on and on. He owned a much broader and deeper library than I imagine one would find in the home or office of many elite professors today.

We quickly got down to business, Mr. Wolfe answering my questions with style, wit and—most importantly—details I didn’t know. Three hours were gone in a flash. I sat listening, enthralled but also terrified that he would cut me off at any moment, cross that I had taken so much of his time.

Instead, he invited me out for lunch. We walked a couple of blocks up Madison—he was stopped on the street three times by well-wishers—to a restaurant where he was obviously a regular. The conversation went on, but not as before. He started asking about me—what I was working on, why the interest in California, and in him. I explained as best I could, mentioning the abandoned Berkeley book. If there were any way I could still do it, he told me, then I must.

And then he paid the check! Can you imagine? After giving me hours of his time, doing me perhaps the greatest favor anyone ever has. I wasn’t going to fight him over it, but I tried every other trick I could think of to get it away from him, to no avail.

We went back to his apartment, where I spent another 90 minutes at least. Finally, I thanked Mr. Wolfe profusely and took my leave. When I emerged back out into the bright sunlight of East 79th Street, I called home. “I don’t want you to take this the wrong way,” I told my wife. “I love you, I love our children, and I love our life.”

A pause. “But?”

“That was the GREATEST DAY OF MY ENTIRE LIFE!”

Two more would come.

I would see Mr. Wolfe at Manhattan Institute events—he was a regular—but now I had the temerity to talk to him. He always seemed glad to see me. He professed himself impressed with my California piece. At one point he said, “I think you know my work better than I do.” Flattery, but—I’ll take it!

Mr. Wolfe eventually disclosed to me that he had an email address and told me what it was. This was like being received into the illuminati. We kept up a sporadic correspondence—I tried to impinge on his time as little as possible. And, since everyone will ask, yes, his emails were punctuated just like his books: inventively.

A bit later, studying Xenophon for reasons I won’t go into here, I noticed several puzzling passages on the subject of women. As I wrote up a scholarly summary of what I had found, I realized that the same observations Xenophon covertly made 2,500 years ago, Wolfe was covertly making today. They were shot throughout his writings, I found as I went back through his work, but given their fullest flowering in I Am Charlotte Simmons, a book I had damned with faint praise. I resolved to make amends—not so much to Wolfe but to readers I had misled.

I asked for, and was granted, another interview. I gingerly explained to Mr. Wolfe that my thesis was that his whole oeuvre is devastatingly subversive to the tenets of Second- and Third Wave feminism. If I had it wrong, I urged him to tell me, because I didn’t want any undeserved taint from my interpretation to attach to him. But he waved me on, so on I went.

The heart of the resulting essay is a reconsideration of Charlotte Simmons, a book I now hold to be a masterpiece. It took me a decade of rumination and other study to “get it,” but once I did, its impact became as indelible as Wolfe’s other books, its theme just as urgent.

That interview had a hard stop because Mr. Wolfe had to be somewhere. As we emerged onto 79th Street, I saw idling under his awning a white Cadillac with white wheels and white interior that I recalled reading about with amusement some years before. In those days he drove it himself, but by now he had a driver. He was headed downtown and offered me a ride—a ride in Tom Wolfe’s white chariot.

“Hello?”

“Hi, Michael, it’s Vanessa. So, we were thinking that for our next Young Leaders event we’d have you do a live, in person Q&A with Tom Wolfe. We reached out to Mr. Wolfe and he likes the idea. What do you think?”

:::::Stunned Silence:::::

Can this be real?

“Uh—HELL YEAH!”

The Harvard Club again. About 250 people, including Tom Wolfe. Except this time, instead of avoiding him, I was on stage with him. Vanessa Mendoza introduced me as a “Tom Wolfe superfan,” which I did not dispute but supplemented with “Tom Wolfe scholar.” Pretentious, but it captured what I had been trying to do. The point was less about me than about him. Despite Wolfe’s immense popularity, which our intellectuals insist is incompatible with seriousness, he was like all great writers first and foremost a thinker whose work rewards study. That it’s all so deliriously fun obscures this fact. I was trying to spread the word.

Tom Wolfe that evening called me “the best-dressed man in New York.” (There is a tape.) To which I replied, “I learned how to dress from The Bonfire of the Vanities.” His eyebrows went up, the corners of his mouth out wide. And then he laughed.

At the time, I held a remunerative and not inordinately demanding corporate job. Writing long essays on the side was fun, but—like Wolfe before Bonfire—I wondered if I were ducking a greater challenge. Deep-sixing the Berkeley book only made the feeling worse. Then I recalled another remark of Allan Bloom’s, praising the scholarly dignity of recognizing one’s limitations and dedicating one’s modest abilities to the service of an unquestionably greater mind.

Of course: a book about Wolfe! He was in New York, I was in New York. The people he knew were in New York. His papers were in New York. I floated the idea to Mr. Wolfe via email. He thought about it for a while, and then agreed to cooperate.

But by then something of a political crisis had erupted. I felt like I had something to say that had to be said and I started saying it—pseudonymously. The book would have to wait.

In May 2016, I had recently become a member of a small supper club to which Wolfe had belonged for decades but had not attended, I was told, in at least five years. At that time, my effort to giving high-brow reasons to support Donald Trump’s presidential candidacy was in full swing. This was, to say the least, a controversial position on the intellectual right. Despite my attempt at anonymity, a few people had figured it out, or at least made educated guesses, and I was too prideful to deny it. Hence, at least in certain quarters of the right, my identity was an open secret.

So I was asked to address the club—an honor in itself, especially for such a newish and relatively undistinguished member—on the subject of Trump. And—Tom Wolfe showed up. I was delighted to see him, of course, and told him so . . . but also surprised, and so asked (I hope in more polite language than this) . . . what the hell was he doing there? Tom Wolfe replied that he had come to hear . . . me.

He sat next to me. Overcome by the double honor, I spent the first half of my remarks giving impromptu comments on the still-underappreciated significance of Tom Wolfe. He didn’t say who he was voting for—he had made that mistake in 2004 and vowed never to repeat it. But he did laugh when I recounted an incident from 1998 that perhaps sheds light on the Trump phenomenon. In New York, mere weeks after the release of A Man in Full, I went to hear Wolfe speak at the Union Square Barnes and Noble. Waiting for him, I happened to be standing next to Elizabeth Berkely of Saved by the Bell and Showgirls fame. We chatted amicably; I don’t think she realized that I knew who she was. When Wolfe came out, among other things, he had to get across to his New York audience just how different Atlanta is. “Down there,” he explained, “real estate developers are big celebrities. In New York, developers are invisible.” Then he added: “Well, except one.” Slowly the crowd got it and a wave of muted laughter spread across the room. Nobody said Trump’s name. Nobody had to.

In transitioning from my impromptu talk to my prepared topic, I noted that Back to Blood—Wolfe’s final and most underappreciated novel—also shed light on the Trump phenomenon. It is a portent of America’s future, unless we can get our arms around certain very large problems—that is, if it is not already too late.

I saw Wolfe one more time, at the Manhattan Institute’s Wriston Lecture later that same year. My life has since gone in a different direction from where it was headed when I pitched him on my book. I fear that that book can never be written—at least not by me. I hope someone worthier undertakes the all-important task.

Tom Wolfe always disclaimed being a man of the right. While we on the right understandably wish to claim him, we should do him the courtesy of taking him at his word. He was unquestionably a patriot—a fact he enthusiastically affirmed. Above all, he was an honest observer, a conveyer of unvarnished, unsentimental, often uncomfortable or unwelcome, truth. In this he shares the essential trait of the philosopher. More than just a writer, he was a rare member of that tribe of philosophically inclined literary men whose work advances philosophic ends.

Until his career’s late-middle (or early-later) stage, Wolfe enjoyed unobtrusively inserting himself into his stories, like a Hitchcock cameo. He would be “a fellow with his legs crossed and a huge chocolate brown Borsalino hat over his bent knee, like he was just trying it on.” Or “some magazine writer in a striped green suit.” The last time he did this (that I noticed) was in Bonfire and that time, uncharacteristically, he disguised himself thoroughly. Silverstein the paparazzo is short, bald, greasy, ugly, badly dressed, with toilet paper stuck to his face—and rude. But he is in the game for the right reason. Silverstein’s high-society publisher gushingly calls him one of “the farmers of journalism. They love the good rich soil itself, for itself. They love to plunge their hands into the dirt.”

Tom Wolfe to a “T.” Perhaps coincidentally (I prefer to think not), the key phrase is nearly identical to the one Xenophon uses—“itself by itself”—to describe Socrates’ ideas (eidos) that Plato immortalized as the “forms.” If we conservatives are right that truth is on our side, or at least closer to what we see than to what we are told to see, then it’s only natural that the reflection in the mirror that Tom Wolfe holds up to the world looks so familiar.

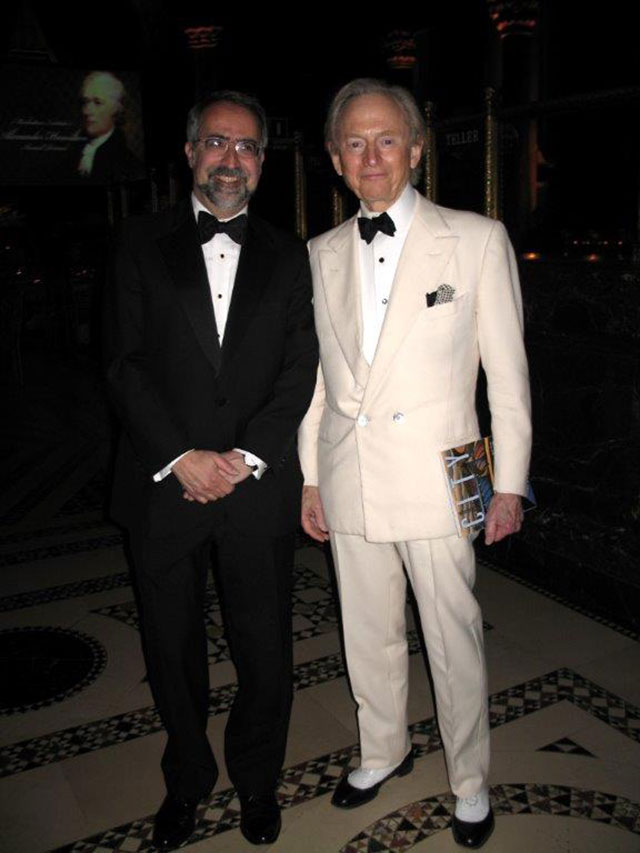

Top and Bottom Photos: Michael Anton and Tom Wolfe in conversation at the Harvard Club, 2014 (All photos courtesy of the Manhattan Institute)