The 2015 academic year opened with protests against two Ivy League universities with campuses featuring buildings named for long-dead, white, southern, and racist politicians—but only one of the protests is getting any attention so far.

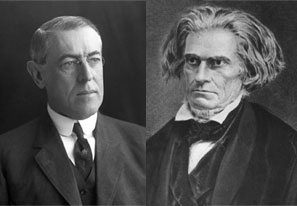

At Yale, the school year began with a demand from students and some alumni that the university change the name of Calhoun College, a residential college named for John C. Calhoun, an antebellum slaveholder, ardent proponent of slavery, and longtime federal officeholder. According to an online petition that circulated over the summer, the murders of nine black churchgoers in Charleston, South Carolina required the removal of “symbols of white supremacy” from all institutions. The petition garnered coverage from the Washington Post, National Public Radio, and USA Today, among others. On September 11, the New York Times reported on a “growing chorus of students, alumni and faculty” demanding a name change.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Around the same time, a student group at Princeton called the Black Justice League began to lobby for the removal of Woodrow Wilson’s name—which adorns a residential college as well as the university’s graduate school of public policy—because of Wilson’s support of segregation. In a September 28 op-ed in the Daily Princetonian, the petitioners—like their Yale counterparts—invoked the Charleston massacre as a reason to “stand up against or acknowledge the wrongdoings of a man who proudly branded himself a racist and segregationist.”

Unlike the Yale petition, the Princeton campaign against Wilson has gained little traction and has received no national media attention. Why? The answer surely has something to do with the fact that Wilson, the founder of the modern Democratic Party, is a progressive icon, while Calhoun is reviled as a proto-conservative.

Historians acknowledge that Wilson’s record on race is deplorable. “Born in Virginia and raised in Georgia and South Carolina, Wilson was a loyal son of the old South who regretted the outcome of the Civil War,” according to Boston University Professor William Keylor. As president, Wilson inherited a federal civil service that had been integrated during Reconstruction, but he authorized the re-segregation of government departments. Wilson tried to prevent black soldiers from serving in combat roles during World War I, opposed Asian immigration on racial grounds, and openly sympathized with the Ku Klux Klan, even organizing a private White House screening of D.W. Griffiths’ notoriously pro-KKK film, Birth of a Nation.

And yet, Wilson remains safely in the liberal pantheon while Calhoun appears to be on the fast track to oblivion. Yale president Peter Salovey responded to the controversy by launching what he described as “a thoughtful, campus-wide conversation,” with conferences and lectures to take place over the course of several months. Unfortunately, this “conversation”—which should focus on the totality of John Calhoun’s legacy—has instead become yet another forum for airing contemporary racial grievances. Campus events ostensibly relating to Calhoun include a conference on “the interplay between race, artistic expression, mass incarceration, and varying perspectives on justice,” a panel on the Charleston shootings, a symposium on “race, gender, sexuality, and academic culture,” and a discussion on affirmative action.

President Salovey’s efforts have barely slowed the rush to judgment. Four days after he announced the “conversation,” the Yale Daily News had already made up its mind: “[W]e must change the name of Calhoun College,” asserted an unsigned editorial, because black high school students are being suspended and black adults are being incarcerated at higher rates than their white peers. At the first Calhoun-related event, one college official declared that the presence of Calhoun’s name on the Yale campus is “an abomination” for which the only solution is “erasure.”

Meanwhile over at Princeton, erasing history turns out to be quite complicated. Having buildings named after Wilson isn’t a matter of honoring a notorious racist, according to Princeton history professor Rebecca Rix, but a phenomenon that invites students to consider “how competing narratives of memory and belonging tie into contemporary identities.” The Yale Daily News interviewed a number of Princeton students who commented on the unfairness of judging Wilson by contemporary standards and the dangerous precedent of focusing exclusively on Wilson’s flaws at the expense of his positive contributions.

The idea of using Wilson’s progressive politics to offset his retrograde racism has been in vogue at Princeton for years. In a 2006 colloquium on Wilson’s legacy, the then-dean of the Woodrow Wilson School called upon the participants to examine the 28th president “as a complicated man, as a man of his times, as a man whom we honor but perhaps we can learn from his failings as well as his strengths.” Eric Vettel, executive director of the Woodrow Wilson Presidential Library downplayed Wilson’s attitude toward and treatment of African Americans as “not [exceptional]” for his times. Another participant in the colloquium urged Princetonians to “disentangle” Wilson’s failures on race from his policy successes.

If Wilson merits such an exquisitely nuanced appreciation from the academic community, doesn’t Calhoun deserve the same consideration? Calhoun was active in national politics for 40 years, serving in the House of Representatives and the Senate, as well as stints as secretary of war to President James Monroe, secretary of state to President John Tyler, and vice president under John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson. Early in his career, Calhoun supported Henry Clay’s program of an activist federal government that would implement infrastructure projects and high tariffs, but he later evolved to become a believer in states’ rights and free trade. He refined the idea of state nullification, a concept first championed by Thomas Jefferson. Yes, he supported slavery, but doesn’t that simply make him “a man of his times,” like Wilson?

Alas, the “progressive” Wilson remains popular in the faculty lounge; regularly ranking among the Top Ten presidents in academic surveys (he does much less well with the general public). Calhoun, on the other hand, is incorrectly blamed for precipitating the Civil War by promoting nullification. In fact, Calhoun’s nullification drive—which related to tariffs, not slavery—was intended to preserve the union by giving states more autonomy. Whether certain college buildings continue to bear the names of Calhoun and Wilson is not, in itself, of much consequence. What matters is whether two great universities have the intellectual honesty to transcend the academic double standard that results in zero tolerance for racists with conservative leanings but a free pass for racists with progressive credentials.