There are many books about happiness. It’s a subject of serious study within the fields of psychology and behavioral economics. So which book on happiness has been on the bestseller list for much of the past two years? One that turned the abstract concept into a “project,” a word so approachable that it implies “something you do with pipe cleaners,” says the book’s author, Gretchen Rubin. The Happiness Project is part of a long American tradition of self-help books dating back at least to Benjamin Franklin. According to Christine Whelan, a University of Pittsburgh sociologist whose doctoral dissertation chronicled the history of self-help, such books doubled as a percentage of overall titles in the U.S. between 1975 and 2000. Today, more than 45,000 self-help titles are in print, and the self-improvement industry does $12 billion worth of business each year.

There is much to mock about titles like the Chicken Soup for the Soul series, which has so many constituent books for teens, preteens, dog lovers, and so forth that it occupies its own shelf in Barnes & Noble. There are serious criticisms, too: that self-help distracts Americans from a fraying social safety net and disintegrating communities, or that an obsession with self-actualization breeds people unwilling to sacrifice for the greater good. But at its best, self-help captures something uniquely American: the belief that anyone can pursue happiness.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

While it has a long history as a legal term, “self-help” was first used in the context of personal development in Samuel Smiles’s 1859 book of that name. Smiles, a Scottish author, urged readers to imitate self-made men of industry. “The spirit of self-help is the root of all genuine growth in the individual,” he wrote. In societies where “men are subjected to over-guidance and over-government,” by contrast, “the inevitable tendency is to render them helpless.” Believing in his own message, Smiles self-published the book after a conventional publisher rejected it. It sold a quarter of a million copies.

Smiles was far from the first person, though, to write a self-help book. The genre had been brewing across the pond for more than a century. According to Steven Starker’s history of self-help, Oracle at the Supermarket, Cotton Mather may have launched the field with his 1710 work Bonifacius: Essays to Do Good. Mather preached the importance of good works within the confines of one’s social role. But a different idea—that one could change one’s social role with effort—soon emerged in the writings of Benjamin Franklin. “Social mobility was presented to the common man as an attainable and worthwhile goal, with Franklin himself an excellent example of the possibilities,” Starker writes.

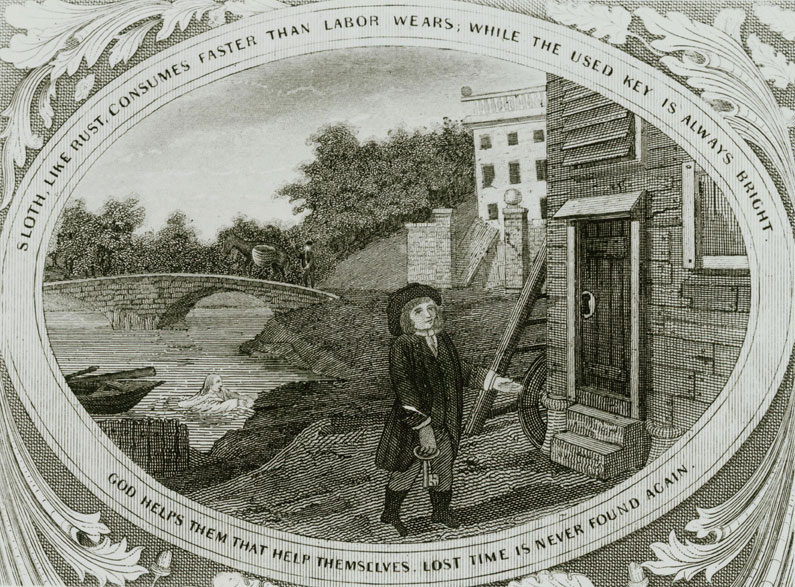

And so Franklin’s 1757 book The Way to Wealth claimed that following such virtues as industry and cleanliness would lead to worldly success; after all, it had done so for Franklin, who was born poor but amassed a fortune as an entrepreneur. Similarly, Franklin’s Poor Richard’s Almanack—which sold well for decades, starting in the 1730s—popularized such sayings as “Would you live with ease, / Do what you ought, and not what you please.” Virtue and prosperity were tightly linked; in Franklin’s view, duty would help one get rich over time. “Keep thy shop, & thy shop will keep thee,” he wrote, a sentiment echoed later in Smiles’s books, the McGuffey Readers’ admonitions to schoolchildren to “try, try again,” and Henry Ward Beecher’s Lectures to Young Men (“The bread which we solicit of God, he gives us through our own industry”).

The genre truly gained steam, though, around the turn of the twentieth century, when a philosophy known as New Thought made self-help more user-friendly by relaxing its fixation on hard work. Rather than seeking worldly success by following God’s principles, proponents of New Thought—a tradition that arose out of both transcendentalism and “mind-cure” proponents, who believed that right thinking could heal ills—advised readers to communicate their desires to God (or some power), who would provide. Attitude is everything; if you believe it, you can achieve it. Ralph Waldo Trine’s 1897 work In Tune with the Infinite taught that “he who lives in the realization of his oneness with this Infinite Power becomes a magnet to attract to himself a continual supply of whatsoever things he desires.” This Law of Attraction became a theme that self-help writers would resurrect regularly for the next century.

New Thought achieved an enduring breakthrough when Napoleon Hill, in 1937, advised a bankrupt nation in his Think and Grow Rich. Close your eyes and think about money, he told readers, and soon it will materialize in your lives. Whether that worked was unclear, but readers figured it didn’t hurt to try, and the book went through dozens of printings. Barnes & Noble still carries the title today.

Around the same time, Dale Carnegie, who had grown up poor and made money teaching public speaking, wrote a book with more practical advice on achieving worldly success. People could advance in their careers and become rich by learning from How to Win Friends and Influence People. Smile, Carnegie wrote. Use people’s names. It was advice your grandmother might spout but packaged for a new managerial class germinating as the modern corporation grew. Unlike many previous books in this genre, How to Win Friends and Influence People (which is also still in print) reads like a modern self-help book, partly because it relates so many anecdotes to back up the author’s advice. A man slated for demotion because of his inability to lead people studies Carnegie’s methods and gets a raise. Abraham Lincoln, frustrated at the escape of Robert E. Lee, elects not to send a critical letter to General Meade. Carnegie knew intuitively that people love stories. So did a slightly later writer, Norman Vincent Peale, whose 1952 bestseller The Power of Positive Thinking comes packed with anecdotes about people who achieved great things and are now sharing the message to “believe in yourself.” (Peale’s chapter titles sound like clichés because so many people have copied them since.)

Self-help books, being popular literature, have always mirrored the larger narratives of their eras. In the 1960s, an interest in Eastern spirituality (encouraged by the Beatles and others) led to self-help focused on meditation and Zen practices. The wrenching social upheavals of the era were also reflected in self-help literature, with the rise of what Steve Salerno, the author of Sham: How the Self-Help Movement Made America Helpless, characterizes as the “victimization” genre. Books like Dr. Thomas A. Harris’s I’m OK, You’re OK were “devoted to telling you why you’re permanently disabled by afflictions implanted on you as a child,” says Salerno. There was an explosion of 12-step programs, along with the relabeling of what had once been considered bad behavior (alcoholism, for example) as disease. While all victimization books had a solution component, the gist was that your problems were the fault of a broken society or of hang-ups bestowed on you by your backward parents or by someone else.

Wide swaths of Americans have never been comfortable with that message, and what Salerno calls the “empowerment” movement was the backlash. Gurus like Dr. Laura (Schlessinger) and Dr. Phil (McGraw) came to prominence in the 1990s preaching that you are responsible for your bad behavior. You probably aren’t blameless about seemingly external troubles such as being broke or brokenhearted, either. As a corollary, you can determine the direction of your life.

Though that’s a nice, upbeat idea, it quickly moved to the extreme, notes Salerno: that you are omnipotent. Anthony Robbins helped make his name with a bestseller called Unlimited Power. Wayne Dyer’s The Power of Intention (2004) claims—in New Thought tradition—that by aligning yourself with an invisible force of energy, you can bring about whatever you desire. Shelves of books now claim that you can do anything if only you let loose your authentic self. Think of such titles as Excuse Me, Your Life Is Waiting; Robbins’s Awaken the Giant Within; and Martha Beck’s Finding Your Own North Star: Claiming the Life You Were Meant to Live. In 2006, Rhonda Byrne rehashed New Thought and the Law of Attraction as a “secret” that great teachers had known through the ages. On the Oprah Winfrey Show and elsewhere, Byrne claimed that The Secret’s followers could have anything, from a parking spot to wealth, just by thinking about it. As Byrne quotes fellow self-help writer Bob Proctor in her book: “Why do you think that 1 percent of the population earns around 96 percent of all the money that’s being earned? Do you think that’s an accident? It’s designed that way. They understand something. They understand The Secret, and now you are being introduced to The Secret.” That, apparently, is all it takes to vault out of the 99 percent.

Self-help books are predominantly an American phenomenon, with the occasional British or Australian accent. While best-selling American titles are translated into dozens of languages, one sees only occasional movement the other way, such as French writer Marie de Hennezel’s The Art of Growing Old, which was a bestseller in France before hitting the American market. Even a foreign-born guru like Eckhart Tolle, the German author of The Power of Now, wrote his bestsellers in English after moving to Canada.

And self-help books are enormously popular—“a Teflon category for many booksellers,” declared Publishers Weekly in 2004. How popular, exactly? Writers like Whelan, Starker, and Salerno have attempted to answer that question by taking a census of such works, but the category is more slippery than it first appears. John Duff, publisher of the Perigee imprint at Penguin, notes that something doesn’t have to be labeled “self-help” to fit the bill. “Personal finance, health, relationships, self-improvement, parenting—all of these fall into the general category,” he says. Many books categorized in the business genre follow the conventions of self-help—most notably, Stephen Covey’s blockbuster The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People—but are labeled differently so that men will buy them. What makes self-help successful is “that strong voice behind it,” says Duff. “You’re listening to that person, they’ve got a point of view, and they do engage you.”

It’s easy to be cynical about the gurus on the bestseller lists and—where the real money is made—on the speakers’ circuit. Robbins hosts weekend seminars that cost from $995 per person for general admission to $2,595 for the “Diamond Premiere” package, which puts you in the first three rows (“Close to Tony!” notes Robbins’s website). Dyer cranks out book after book; a postcard-size one called Staying on the Path goes for $8.95 and features such deep thoughts as “Schools must become caring places full of teachers who understand that teaching students to love themselves and feel positive about their natural curiosity ought to be given as much attention as geometry and grammar.” When a title goes big, a smart guru (or the guru’s coauthors) will write sequels—The Power of Focus breeds The Power of Focus for Women—and tout ancillary products: calendars, DVDs, dietary supplements. Gurus use the honorific “Dr.” liberally. Dr. Laura’s degree is in physiology, not psychology or psychiatry, and Dr. John Gray, creator of the Men Are from Mars, Women Are from Venus juggernaut, got his doctorate from Columbia Pacific University, a nonaccredited correspondence college.

Another reason to be dubious about the self-help genre is that as it becomes more and more crowded, authors correspondingly ratchet up their books’ purported benefits. Consider The 4-Hour Workweek, the 2007 bestseller in which Tim Ferriss, a 20-something entrepreneur, pledged that readers could “escape 9–5, live anywhere, and join the new rich” by outsourcing tasks and creating “passive income streams.” And while claiming that you can work four hours a week in this economy is mind-blowing enough, Ferriss’s next book, The 4-Hour Body, goes beyond that to seem to promise 15-minute orgasms (ladies only).

Then there’s the question of whether self-help works at all. “To be frank, most self-help books are disappointing,” says Whelan. “They often blame the victim with the implied message that the advice in the book works, and if it doesn’t work for you, you didn’t try hard enough. They often seek to solve problems that can’t really be solved by reading a book on your own. They use composite stories to create idealized examples of how the advice works, which only leads real people to wonder why they keep failing.” Salerno recalls that when he was working as the editor of the books program associated with Rodale’s Men’s Health magazine, he learned that “the most likely customer for a book on any given topic was someone who had bought a similar book within the preceding eighteen months.” That’s one thing when you’re talking about Civil War books, he says—but doesn’t it imply that the first self-help book didn’t solve the reader’s problem? Salerno even argues that “the self-help guru has a compelling interest in not helping people.”

The self-help tradition has attracted critics of its substance as well. Micki McGee, a professor of sociology at Fordham University and author of Self-Help, Inc.: Makeover Culture in American Life, notes that, since the 1970s, the growth in self-help has paralleled the destabilization of the labor market and of families. “In place of a social safety net, Americans have been offered row upon row of self-help books,” she says. A declining number of people have a lifelong profession or a lifelong marriage, and so “it is no longer sufficient to be married or employed; rather, it is imperative that one remains marriageable and employable.” Self-help books prey on our insecurities—that our bosses don’t consider us highly effective people, or that our spouses wonder where those 15-minute orgasms are. Taking issue with the “empowerment” school, she points out that “the idea that you’re completely in charge of your own destiny has as its inverse that if anything happens to you, you are to blame.” And if things go well? Self-help is steeped in “that painful, self-congratulatory aspect that American success has. It’s not enough to be successful, you get to take full individual credit for it,” as if no one had helped you along the way. “Our indebtedness to each other is erased in this literature,” McGee says.

Even if you like the idea of rugged individualism, the critics claim that self-help takes it too far. Self-help books preach that “if you believe it enough, that will carry you through,” says Salerno. “It strips away the value that we used to have for things like hard work and planning.” As for believing that one’s authentic self must be freed from society’s restrictions, that ignores the fact that those restrictions are there for a reason. “I think it’s safe to say that Charlie Manson was fully self-actualized,” Salerno muses. “Does it not make sense that a society in which everyone seeks personal fulfillment might have a hard time holding together?”

Still, just because there’s plenty to criticize doesn’t mean that there isn’t plenty that’s worthwhile, too. As Gretchen Rubin points out, all branches of knowledge have their quacks: “When you have your astronomy, then you get your astrology—and we have our own astrologers in this neck of the woods.” Nonetheless, “the greatest minds throughout history have thought about things like self-knowledge and self-control and how to live a good life. I don’t know why it’s now branded as snake-oil stuff.” Even the most over-the-top books offer a real benefit: they encourage the virtue of self-examination. To read self-help is to take stock of one’s self and to ask what kind of life one wants to lead.

These are profound issues, and what the genre’s critics sometimes miss, too, is that self-help readers are well equipped to explore them. That’s because the people who buy these books are, like all book buyers, “pretty comfortable,” says John Duff of Penguin. “It’s going to be that middle-class person, reasonably well-educated” and in “very rarefied” company, as “our market for all books is really very limited. Most people stop reading when they leave school.” Those who don’t stop probably have their acts together. Call it the paradox of self-help. “The type of person who values self-control and self-improvement is the type of person who would seek more of it in a self-help book,” Whelan says. “So it’s not the unemployed crazy lady sitting on the couch eating potato chips who reads self-help. It’s the educated, affluent, probably fairly successful person who wants to better themselves.”

Consequently, self-help readers rarely do everything that a book advises; after examining their own lives, they use their judgment to decide what’s worth trying. Rubin reports that her readers “pick one or two things and they feel good about it. They pick the things they feel are right for them.” Hyperbole from gurus like Robbins is best viewed not as serious advice but as motivation for the hard work of personal change.

And if you do want something more thoughtful, Whelan agrees with Rubin that several titles lean toward the astronomy side of self-help—particularly those that celebrate old-fashioned virtues of the sort that Ben Franklin espoused. For her 2011 book for 18-to-25-year-olds, Generation WTF: From “What the #%$&?” to a Wise, Tenacious, and Fearless You, Whelan asked her college students to test-drive advice from classic self-help titles that she deemed worthwhile. Among others, these included The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People (1989), which preaches self-discipline and treating others as you would like to be treated, and M. Scott Peck’s The Road Less Traveled (1978), which tells readers to delay gratification and to understand that “life is difficult.” Whelan’s students apparently found these books useful; 95 percent said that the advice was valuable to their lives, and 92 percent reported that they had learned something new about themselves. For them, self-help was helpful.

Alisa Bowman is a believer. A journalist based in Emmaus, Pennsylvania, she reports that her marriage was in such dire straits a few years ago that she fantasized about her husband’s funeral. But before filing for divorce, she decided to try therapy and the advice in various relationship self-help books. She found the books so useful (“You get to pick the brains of hundreds of experts”) that she never got around to seeing a therapist. In particular, she thought that John and Linda Friel, authors of The 7 Best Things (Happy) Couples Do, “completely understood the kinds of problems I was facing, and their advice seemed doable.” She approached all the books with the attitude that she was in charge of this project, could evaluate people’s credentials as a smart consumer, and could ignore advice she found silly. Bowman learned to take ownership of problems that weren’t her husband’s fault, to communicate more clearly when she wanted help, and to be more loving. After four months, the couple renewed their vows (an experience that Bowman wrote about in her 2010 memoir Project: Happily Ever After). “The advice actually worked,” she says. “It didn’t work overnight, but they weren’t promising that.”

Melissa Cassera, a New Jersey publicist, adopted a similar attitude when reading The 4-Hour Workweek. “Tim Ferriss doesn’t work four hours a week. That’s stupid,” she says. What she learned from the book was not to outsource her tasks to Indonesia; it was that she and her husband could have adventures in their thirties that many people put off until retirement. “If it is important to us to go travel, we can do that now,” she says. “There is a way to do this that honors our businesses and lifestyle.” Ferriss’s book provided inspiration to look into plane tickets. That’s not bad for $12.99 on Kindle.

Indeed, it’s very American to think that we can better our lives by picking and choosing from inspirational tomes that are available to anyone with a spare $20. We don’t believe that people who are rich, or who have steamy marriages, are fundamentally different from the rest of us. We believe that they have discovered some knowledge that is accessible to us as well. The fact that we choose our gurus according to who seems most compelling is also very American. We have no state religion, and few of us do things just because our great-grandparents did. We don’t listen to a village elder who tells us what the good life looks like. Instead, we construct it ourselves, from what we see of the world around us—and what we find at the bookstore.

That reflects the philosophy of our Founding, says Indiana University folklorist Sandra K. Dolby, whose treatise Self-Help Books: Why Americans Keep Reading Them takes an anthropological look at these mixtures of case studies and morals. Americans have long celebrated education outside the school, she notes, from libraries to mutual improvement societies. A democracy requires thoughtful citizens who believe that society can improve with effort. Is it surprising that such citizens believe that they can improve with effort, too? The Founders “wanted people to be thinking of being the best kinds of people they could be, if the democracy was going to succeed,” Dolby says.

And so, living out the Founders’ expectations, we undertake our happiness projects, trusting that with hard work—and perhaps a few positive thought vibrations—we can succeed. “Americans think they can find a way to fix anything,” says Dolby, “including themselves.”

Top Photo by Tim Boyle/Getty Images