Hotel: An American History, by A. K. Sandoval-Strausz (Yale University Press, 384 pp., $35)

In March 1776, James Boswell and Samuel Johnson journeyed by post-chaise to Oxfordshire to take in the incomparable Blenheim Palace, which England had built for John Churchill, Duke of Marlborough, in gratitude for his routing the French in the Battle of Blenheim. Afterward, dining in a nearby inn, Johnson considered the relative merits of private houses and public inns. As Boswell related in his biography of Johnson:

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

There is no private house, (said he,) in which people can enjoy themselves so well, as at a capital tavern. Let there be ever so great plenty of good things, ever so much grandeur, ever so much elegance, ever so much desire that every body should be easy; in the nature of things it cannot be: there must always be some degree of care and anxiety. The master of the house is anxious to entertain his guests; the guests are anxious to be agreeable to him: and no man, but a very impudent dog indeed, can as freely command what is in another man’s house, as if it were his own. Whereas, at a tavern, there is a general freedom from anxiety. You are sure you are welcome: and the more noise you make, the more trouble you give, the more good things you call for, the welcomer you are. No servants will attend you with the alacrity which waiters do, who are incited by the prospect of an immediate reward in proportion as they please. No, Sir; there is nothing which has yet been contrived by man, by which so much happiness is produced as by a good tavern or inn.

In his well-researched and well-illustrated history, A. K. Sandoval-Strausz shows how the purpose-built American hotel evolved from the often-improvisational inn. George Washington’s presidential tours of the states from 1789 to 1791 first demonstrated to the young nation what social, political, and economic advantages good inns could offer. Leading citizens, local officials, and old comrades-in-arms tried to persuade the first president to put up in their houses, but Washington insisted on staying at inns: they would avoid any appearance of favoritism and give him a feel for the pulse of the places he visited. The tours helped unify the fractious young nation by giving citizens forums for debating and resolving disputed issues. In the process, inns became famous for having hosted the president—New York’s own Fraunces Tavern is proof of that—and they increasingly sought to improve services and accommodations.

Thus was born the American hotel. Its development, like that of so many other things in the new republic, was rapid. At the beginning of Washington’s tours, even the best inns were ramshackle affairs of three floors and 20 rooms, costing no more than $15,000; by 1809, the best hotels could boast as many as seven floors and over 200 rooms, and cost more than a half a million dollars.

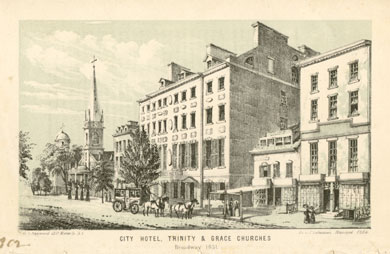

Sandoval-Strausz, who teaches history at the University of New Mexico, charts the history of this quintessentially American institution with élan. The first great American hotel was New York’s City Hotel, built in the fashionable Federalist style between lower Broadway and Temple Street in 1794. Its interior included a ballroom, public parlors, a bar, stores, offices, and the country’s largest circulating library. Offering 197 rooms, mostly for overnight guests, the City Hotel was taller than all but the loftiest New York churches, and with a $200,000 price tag, it was also the city’s costliest building, with the exception of the newly built headquarters of the New York Stock Exchange on Wall Street. The hotel became so popular with Gotham business leaders that they moved the Custom House there. The City Hotel’s success and prestige inspired other hoteliers around the country to try to emulate it.

Most of the businessmen who backed hotel development in the United States had interests in far-flung international trade. They were players in a global economy long before that term became commonplace. While 90 percent of early-nineteenth-century Americans earned their living from farming, the nation’s entrepreneurial elite were dedicated to improving the transportation of goods, and for this they needed places to sleep, to transact business, and to entertain. “Merchants in general and the hotel builders in particular had a vested interest in the speed and reliability of transportation,” the author writes. There was also a strong link between railroads and hotels. Railway magnate George Pullman built the Hotel Florence not only for business travelers, but also for tourists eager to see the model community—Pullman, Illinois—that he had created for the workers building his famous Pullman sleeping carriages. The red brick building still stands.

Hotels were thus vital to the country’s expansion. Baltimore’s City Hotel opened in the 1820s, rivaling New York and Boston hotels in size and grandeur. It was also illuminated by gaslight—a dazzling innovation in those Cimmerian days. Its designer, William F. Small, was influenced by Benjamin Latrobe, one of the many talented architects commissioned to design hotel exteriors and interiors. An Englishman educated in Prussia, France, and Italy, Latrobe immigrated to the United States in 1796. In addition to designing the United States Capitol, he left behind brilliant plans for a Richmond Hotel, which was to include a ballroom based on the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles. Alas, the plans were never executed: what was then the country’s eleventh-largest city found them too grand and too expensive. In the late nineteenth century, another Englishman, Fred Harvey, built the Montezuma Hotel in Las Vegas, New Mexico, featuring the “Harvey Girls,” hotel staffers required to perform their tasks in starched black-and-white uniforms without jewelry or makeup. These were clearly not the inspiration for the Vegas showgirls of Las Vegas, Nevada.

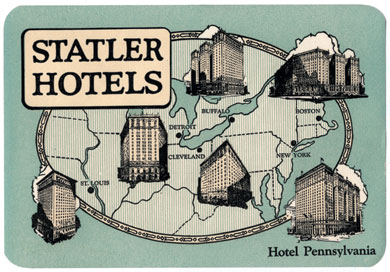

Sandoval-Strausz touches on later developments, too, including the creation of chain hotels—pioneered by the Procrustean E. M. Statler, who standardized accommodations throughout the country—and the rise of resort hotels in places like the Catskills and Saratoga. Then there was the great movement to make hotels as luxurious as possible, exemplified by Denver’s Brown Palace and New York’s Waldorf-Astoria and the Plaza, which went up in just two years at a cost of $12.5 million in 1907. The Jumeirah Essex House in New York, owned by Dubai, has continued the trend, sinking many more millions into its Central Park South property to attain a comparable sumptuousness.

Reading Hotel: An American History, one is struck by how soon the hotel as we know it was up and running. By the early nineteenth century, hotels had already become what they continue to be in the twenty-first: meeting places for politicians and businessmen, reception spaces for the newly wed, retail outlets for shoppers, getaways for tourists, hideaways for adulterers. In the nineteenth century, enterprising prostitutes threatened the reputations of even the best hotels; books of hotel etiquette warned unwary guests against them. “Have little to say to a woman who is traveling alone without a companion,” advised one, “and whose face is painted, who wears a profusion of long curls about her neck, who has a meretricious expression of eye, and who is overdressed.” By the same token, respectable women were urged to behave accordingly. “Any bold action or boisterous deportment in a hotel will expose a lady to the most severe censure of the refined around her, and may render her liable to misconstruction, and impertinence.” The Barbizon Hotel on East 63rd Street in New York freed women of these dangers by giving them a hotel of their own. Sadly, a drab gymnasium now obscures its fanciful jumble of Gothic, Islamic, and Italian Renaissance styles.

Now that so many beautiful old New York hotels are closing down altogether, or converting partly or entirely into residential properties—one thinks of the Stanhope, the Plaza, the Carlyle, and the Pierre—Samuel Johnson’s preference for the public inn over the private house no longer seems the popular choice. Yet for those expansive souls who like to make noise and give trouble, while calling out for more good things, the inn will always beat the private house hollow.