This is the second of two essays exploring James Madison’s thought and importance in American history; the first appeared in our Winter 2011 issue.

By the summer of 1788, the states had ratified the Constitution James Madison had conceived and guided through the 1787 Philadelphia Convention, and the following spring the new governmental machinery that the great document devised hummed into motion smoothly—though with a bump for Madison. Patrick Henry, doubting his fellow Virginian’s ratifying-convention assurances that the newly strengthened federal government would never abolish slavery, made sure Madison didn’t become one of the state’s senators, declaring his election would produce “rivulets of blood throughout the land.” He tried to keep the 37-year-old federalist from being elected congressman, too, by gerrymandering his district to make him run against his friend James Monroe on Monroe’s home turf. Despite his distaste for politicking, Madison campaigned gamely, debating Monroe for hours in the snow and getting a frostbit nose on the frigid ride home. He won, 1,308 to 972—and bore his frostbite battle scar for life.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Heading to New York for the opening of Congress, Madison stopped at Mount Vernon and drafted president-elect George Washington’s inaugural address—to which, as Congress’s de facto leader for its first two years, he wrote the legislature’s ceremonial reply. He helped the new president choose cabinet secretaries, remained his closest advisor until those appointees took over, and set the new government going on April 8, 1789, by proposing import duties to fund it. On April 30, he marched with the president to his inauguration as one of five congressional escorts.

Madison’s chief goal that year was to get the Bill of Rights through Congress. He had at first strongly opposed such amendments, arguing that the Constitution, by its precise enumeration of the federal government’s strictly limited powers, makes clear that any power not on that short list remains off-limits. A bill of rights would reverse the emphasis, he feared, opening the way to an enlargement of federal prerogative and a shrinking of the powers reserved to the states and the people. “If an enumeration be made of our rights,” he argued in the June 1788 Virginia ratifying convention, “will it not be implied, that every thing omitted, is given to the general government?”

But the ratifying convention changed his mind. In his belief that rights inhered in the people, he was in the vanguard of political thought: under the new Constitution, he knew, Americans didn’t have rulers; they had public servants. Yet since many of his republican compatriots remained stuck in the old view of rights as something to be wrested from rulers, he saw that he couldn’t muster a majority in favor of the Constitution without vowing that he and his fellow federalists would promptly pursue a bill of rights. “As an honest man, I feel my self bound by this consideration,” he wrote.

A few months later, he had persuaded himself that this pragmatic position was principled. “My own opinion has always been in favor of a bill of rights,” he disingenuously wrote Thomas Jefferson, “provided it be so framed as not to imply powers not meant to be included in the enumeration.” Not that such “parchment barriers” would prevent “overbearing majorities” from violating individual rights: “Wherever there is an interest and power to do wrong, wrong will generally be done,” he drily observed. But a bill of rights could beneficially shape the nation’s political culture. “The political truths declared in that solemn manner acquire by degrees the character of fundamental maxims of free Government, and as they become incorporated with the national sentiment, counteract the impulses of interest and passion.”

What’s more, warily attentive to his constituents ever since a 1777 electoral defeat, he had made promises about a bill of rights in the 1789 congressional campaign that he felt duty-bound to honor. “Antifederal partizans” had warned Baptists in his district that he “had ceased to be a friend to the rights of Conscience.” However implausible, the rumor gained traction, so he responded with letters to a newspaper and a key Baptist preacher pledging support for a bill of rights, “particularly the rights of Conscience in its fullest latitude.” By the time he proposed the Bill of Rights on June 8, 1789, he told his fellow congressmen that he wished they had made it “the first business we entered upon; it would stifle the voice of complaint, and make friends of many who doubted [the Constitution’s] merits.”

Only one disappointment tempered his pleasure in the result. He wanted the Bill of Rights to include an amendment protecting citizens against state violations of “the equal rights of conscience, or the freedom of the press, or the trial by jury in criminal cases,” which, in his view, would be the “most valuable amendment on the whole list”; but his fellow congressmen wouldn’t cede so much of the states’ powers in the name of individual rights. He graciously acquiesced, “as a friend to what is attainable.” It would not be until after the Civil War that the Fourteenth Amendment extended the Bill of Rights to ban infringements of constitutional rights by the states—though the Supreme Court’s Slaughter-House Cases decision narrowed that protection in 1873.

Congress submitted the Bill of Rights to the states on September 25, 1789, and long before they had finished ratifying the ten amendments during 1791 and ’92, Treasury secretary Alexander Hamilton had seized the initiative of the new government from Madison with his sweeping plan for reorganizing the nation’s finances at the start of 1790, igniting a smoldering feud with the Virginia congressman that ended in an explosive battle over what the Constitution meant. In his January Report on Credit to Congress, Hamilton had proposed restructuring the nation’s $76 million of war debts by calling them in and replacing them with interest-bearing long-term notes backed by specially designated tax revenues, so that holders would be certain they’d be repaid and would receive their interest like clockwork. If the nation’s credit really were good—meaning that people believed they would get paid back—such notes could serve as money, a universally accepted medium of exchange that would grease the wheels of industry and commerce, call forth the nation’s full productive capacity, and multiply its real wealth. Hamilton’s Treasury could also use the special fund to buy bonds whenever they dropped in price, ensuring they’d keep their value instead of depreciating away like the evanescent Revolutionary War paper currency.

The debts Hamilton wished to reorder were a messy mix of federal and state promissory notes held by a variety of creditors, ranging from soldiers who’d taken them as their pay to investors who’d bought up the notes at big discounts from cash-strapped veterans or suppliers. The only way to make his new U.S. notes as good as gold, Hamilton saw, was for the federal government to make itself responsible for the state debts and to treat every piece of government paper as worth its face value, so that henceforward everyone would understand that “full faith and credit” meant what it said. Seven years earlier, Madison, in consultation with Hamilton, had proposed to Congress a financial plan that included exactly such a federal assumption of state debts, and, just as Hamilton was now urging, he had also pleaded with the states not to discriminate among different classes of creditors.

But now Madison turned against these ideas and against his Federalist Papers collaborator, and in his much later fragment of autobiography, he took pains to claim that he hadn’t understood back in the 1780s “the magnitude of the evil” of leaving soldiers who had sacrificed so much with pennies on the dollar, while speculators and “stockjobbers,” as Madison called them, raked in the lion’s share of the money originally owed the battle-worn veterans. As for federal assumption of state debts, Virginia and other states had already paid off their debts, so in helping to pay the debts of other states with their taxes, Virginians would in effect be paying for the war twice—though the state in fact had discharged its own debt also for pennies on the dollar. Accordingly, Madison blocked Hamilton’s plan in Congress all through the winter and spring of 1790.

But as one of the few Founders who had never been a lawyer, a soldier, or a foreign envoy, Madison was a practical, professional politician—indeed from this moment even a political party leader—and he was willing to make a deal. Over a famous Madeira-fueled dinner at Jefferson’s rented house on Maiden Lane in late June, Madison agreed to get two of his Virginia allies to vote for the funding plan, in exchange for Hamilton’s pledge to persuade some Pennsylvania congressmen to vote for building the nation’s permanent capital on the Potomac. By August, Congress had passed both measures.

But Madison’s resistance to Hamilton’s plan ran deeper than such horse-trading could reach. Uneasy about northern power now that the Great Compromise, which gave each state equal representation in the Senate, had assured northern dominance of that body, he had no wish to boost northern economic might further, as Hamilton’s plan would do, since northern states had the most debts for the federal government to pay off, and speculators in depreciated government paper were mostly northerners. Some of those speculators, he learned to his disgust, were “members of Congress, who did not shrink from the practice of purchasing thro’ Brokers the certificates at little price,” knowing they would then vote “to transmute them into the value of the precious metals.”

Nor did Madison like Hamilton’s idea of a funded debt, perpetually rolled over, never extinguished, and requiring taxation to service it. Such a market in government paper called into being a class of financiers and investors, dependent on the Treasury and prone to corruption. Madison feared that “the stockjobbers will become the praetorian band of the Government,” he told Jefferson, “at once its tool and its tyrant.” Indeed, the Treasury faction could gain enough political might to carry all before it.

After Jefferson returned from France in late 1789 and the two Piedmont neighbors began working together during Washington’s presidency, the friendship between Secretary of State Jefferson and Congressman Madison deepened, with Jefferson’s radical republicanism fanning Madison’s own republican flame. Madison remained an independent thinker, of course, and had no trouble pooh-poohing Jefferson’s wilder notions, including his airy dismissal of Madison’s hope that the Constitution would last: “No society can make a perpetual constitution, or even a perpetual law,” Jefferson scoffed. But John Randolph of Roanoke, the outrageous House Ways and Means chairman who thought himself the purest—indeed, the only—republican, hit a truth in saying, “Madison was always some great man’s mistress—first Hamilton’s,—then Jefferson’s.”

Without doubt, Madison craved Jefferson’s approval, and that passion deeply if subliminally tinged his worldview and shaped his career thereafter. As John Quincy Adams judged, “The mutual influence of these two mighty minds upon each other is a phenomenon, like the invisible and mysterious movements of the magnet in the physical world, and in which the sagacity of the future historian may discover the solution of much of our national history not otherwise easily accountable.”

Not long after he left Princeton, Madison had warned his friend William Bradford against “the impertinent fops” who “breed in Towns and populous places, as naturally as flies do in the Shambles, because there they get food enough for their Vanity,” but this conventional literary trope began congealing into Jeffersonian rural sentimentality by the 1790s. “The life of the husbandman,” Madison declared in a 1792 article on republicanism, is the best life for “health, virtue, intelligence, and competency in the greatest number of citizens,” not to mention “liberty and safety” for all. The life of workers in the various “branches of manufacturing, and mechanical industry,” to the extent it differs from the yeoman’s life, is proportionally less “truly independent and happy.”

How bad can it get? he asked in a subsequent article. Take the buckle-makers of Britain, 20,000 of whom have lost their jobs and are “almost destitute of bread” because the trendsetting Prince of Wales, a “wanton youth” acting on “a mere whim of the imagination,” has chosen to tie his shoes rather than buckle them. You don’t find such “servile dependence of one class of citizens on another class” among “American citizens, who live on their own soil,” exempt from “the mutability of fashion.”

The well-known bad faith in this pose still jars. In 1792, Madison’s younger brothers managed the Montpelier plantation, along with their father, nearing 70; the congressman had surely never set hand to plow. Jefferson, who as minister to France had himself painted in 1786 in a daintily curled wig, striped silk waistcoat, and dandified ruffled shirt, with a matching expression of supercilious foppery worthy of any ancien-régime aristo, did run his own plantation, using the most modern methods. But sturdy yeomen? These hereditary landed grandees had their farming done for them by slaves. Their dependence on another class, though tyrannical not servile, was just as absolute as that of the buckle-makers of Britain. They wanted the fiction of being republican husbandmen, “who provide at once their own food and their own raiment,” as Madison rhapsodized, in order to oppose their self-proclaimed virtue and down-to-earth economy to urban life’s foppery and fashion, phantom paper wealth, speculative bubbles, useless and precarious occupational diversity, vice, debauchery, debt, and disease. No finance capitalism for them, no large-scale industry, no northern cosmopolitanism—in short, no Hamiltonianism.

The last straw for Madison was Hamilton’s December 1790 proposal for a federally chartered bank, empowered to print money, sell stock, and make loans to the government and private entrepreneurs. The capstone of Hamilton’s financial edifice, the bank would leverage $2 million of precious metal into $10 million in currency, enough to galvanize the nation’s economy into full productive bustle. Madison, writing in the National Gazette—a snarling opposition tabloid he and Jefferson had encouraged his old Princeton friend Philip Freneau to start—thundered that such a measure would only “pamper . . . speculation,” “promote unnecessary . . . debt,” and “encrease . . . corruption”—all “in opposition to the republican spirit of the people.” Understandably scarred by the inflation of Revolutionary War paper currency, Madison, now the hardest of hard-money fundamentalists, didn’t understand how paper money—firmly anchored in specie and backed by reliable credit—could safely increase both the quantity and velocity of money, greatly enlarging the money supply. All the bank would accomplish, he told Congress in February 1791, would be to banish precious metals abroad and substitute another medium of exchange for them, without increasing the overall quantity.

As this speech gathered steam, Madison moved beyond such backward-looking mercantilism and magnificently set forth his main point: that the Constitution did not give Congress the power to establish an incorporated bank. Hamilton, he said, was urging the legislators to charter the bank based on the power that Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution gives them “to make all laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the foregoing Powers”—specific, limited powers that the section had just enumerated. But notice what “ductile” language Hamilton must use “to cover the stretch of power contained in the bill.” As the bill puts it, the bank “might be conceived to be conducive to the successful conducting of the finances; or might be conceived to tend to give facility to the obtaining of loans,” Madison quoted, adding emphasis oozing with incredulous contempt. So to begin with, the bank wasn’t even “necessary,” as the “necessary and proper” clause required; “at most it could be but convenient.”

Worse, Madison suggested, Hamilton’s reliance on a doctrine of implied powers instead of explicit ones courted disaster. “The doctrine of implication is always a tender one,” he warned. “Mark the reasoning” behind the bill: “To borrow money is made the end and the accumulation of capitals, implied as the means. The accumulation of capitals is then the end, and a bank implied as the means.” By such a chain of implication, we end up with “a charter of incorporation, a monopoly, capital punishments, &c.,” until finally we take in “every object of legislation, every object within the whole compass of political economy.” In that case, Madison cautioned, the “essential characteristic of the government, as composed of limited and enumerated powers, would be destroyed,” and Congress would bear “the guilt of usurpation.” We should not, he later wrote, “by arbitrary interpretations and insidious precedents . . . pervert the limited government of the Union, into a government of unlimited discretion, contrary to the will and subversive of the authority of the people.”

Here we stand at one of the fateful crossroads of American history. One great man proposes a brilliant innovation that another great man says the Constitution whose design team he led does not permit. What should have happened?

Madison himself provides an ideal model. In the Constitutional Convention, he and Pennsylvanian James Wilson had moved to give Congress power to build canals, but their colleagues rejected the plan as costly and unnecessary. Three decades later, on his last day as president, March 3, 1817, Madison vetoed a bill providing federal funds for canals and roads. “I am not unaware of the great importance of roads and canals,” his veto message conceded; nor did he doubt that spending federal money on them would yield “signal advantage to the general prosperity.” But the power to do so is not among the powers “specified and enumerated” in Article I, Section 8, and any reading of the “necessary and proper” clause, or the commerce clause, or the clause “to provide for the common defense and general welfare” that would justify Congress’s exercise of such power “would be contrary to the established and consistent rules of interpretation”—which, Madison explained at different epochs in his life, should stick to what those who had framed and ratified the text meant by it. “Such a view of the Constitution,” the veto message concluded, “would have the effect of giving to Congress a general power of legislation instead of the defined and limited one hitherto understood to belong to them.” If legislators want to build roads and canals, let them frame a constitutional amendment asking the people for the requisite power. Couldn’t be clearer.

But even Madison didn’t always find it so.

At other times, he willingly embraced the doctrine of implied powers himself. As early as 1781, he had asserted Congress’s “implied right of coercion” of the states, by gunboats if need be, to make them send in their share of Revolutionary War supplies. And in his defense of the “necessary and proper” clause in Federalist 44 against those who thought it too elastic, he pointed out that the Constitution purposely didn’t follow the Articles of Confederation in prohibiting Congress from exercising “any power not expressly delegated” to it, because no legislative body can carry out its duties “without recurring more or less to the doctrine of construction or implication.” It would otherwise face “the alternative of betraying the public interest by doing nothing; or of violating the constitution by exercising powers indispensably necessary and proper; but at the same time, not expressly granted.” In words Hamilton later flung back at him, Madison concluded, “No axiom is more clearly established in law, or in reason, than that wherever the end is required the means are authorised; wherever a general power to do a thing is given, every particular power necessary for doing it, is included.” And even as recently as the debates over the Bill of Rights, Madison had dissuaded his colleagues from wording the Tenth Amendment so that it would reserve to the states and to the people powers not expressly delegated to the United States. Not even the Constitution, he argued, could foresee every eventuality, so some latitude was in order.

He found he needed that flexibility when, as secretary of state, he opposed President Jefferson’s strict constructionism and embraced Hamilton’s broad-construction constitutional approach to justify the Louisiana Purchase. With the army Napoleon had sent to quell the slave revolt in Haiti destroyed, and the fleet he had readied to reinforce its planned occupation of New Orleans icebound in Holland, the French dictator concluded that he now had no geostrategic use for the Louisiana Territory and would be better off at least getting some money for it by selling it to the Americans. The flabbergasted American envoys in Paris, James Monroe and Robert Livingston, only realized that Napoleon wasn’t joking about offering to sell when Madison’s old friend François Barbé-Marbois solemnly assured them that the offer was serious—but that time was short.

Jefferson observed that the Constitution gave neither the president nor Congress power to pay $15 million to double the size of the United States, but Madison argued that the deal was too good to lose and that Congress’s treaty-making power implied a power to buy land, so Jefferson decided to shelve the constitutional amendment he had already drafted and “acquiesce with satisfaction” in Madison’s view. Madison confessed to Senator John Quincy Adams that the Constitution didn’t entirely authorize the transaction, but he expected that the “magnitude of the object” would excuse the stretch.

In the case of Hamilton’s bank, what actually happened was this. After the House and Senate approved it by big majorities, President Washington, troubled by Madison’s opposition, asked him to prepare a veto message, just in case, and he asked Jefferson and Attorney General Edmund Randolph for their written opinions about the bank’s constitutionality. They echoed Madison’s objections, and Washington sent their memos to Hamilton for rebuttal.

In his extensive, forceful brief—which urged interpreting the Constitution “on principles of liberal construction” (liberal not in a partisan sense but in the sense of free, open-minded, unprejudiced, expansive rather than crabbed)—Hamilton argued that the “criterion of what is constitutional . . . is the end to which the measure relates as a mean. If the end be clearly comprehended within any of the specified powers, & if the measure have an obvious relation to that end, and is not forbidden by any particular provision of the constitution—it may safely be deemed to come within the compass of the national authority.” Moreover, Hamilton advised the practical-minded president, “All the provisions and operations of government must be presumed to contemplate things as they really are.” Washington received Hamilton’s brief on February 23, 1791, and signed the bill into law the next day, providing all the “energy in government” that Madison had once sought—and more—and supercharging American prosperity.

In the summer of 1798, when President John Adams signed the Alien and Sedition Acts—for which Vice President Jefferson justly dubbed his administration “the reign of witches”—Madison had to ponder a starker constitutional question: What is the right response to federal measures so grossly unconstitutional that they trample liberty? As the Napoleonic Wars raged across the globe and the United States found itself locked in an undeclared but costly naval “Quasi-War” with France, U.S. diplomats sought peaceful relations, only to meet with demands for a £50,000 bribe from their French counterparts, code-named X, Y, and Z in their dispatch. When news of the XYZ Affair reached America in March 1798, with reports (slightly embellished) that the American envoys had indignantly replied, “Millions for defense, but not one cent for tribute,” national politics, which had already split into two hostile parties over Hamilton’s bank bill, reached its climax of bitterness.

Adams and Hamilton’s Federalists tarred Madison and Jefferson’s Republicans as dupes or fifth-columnists for clinging to their affection for France all through the Reign of Terror and the rise of Napoleon—and indeed X, Y, and Z’s dark hints of aid from “friends of France” in America, as the published diplomatic dispatches reported, fanned the hysteria that hatched the Alien and Sedition Acts. Republicans dismissed the Federalists as Francophobe “anglomen,” pageantry-loving “monocrats,” and plutocratic stockjobbers, who were using French misbehavior as an excuse to forge a British alliance and move toward a British-style monarchy or hereditary aristocracy, British-style political corruption, and a British-style standing army that would underpin a British-style “fiscal-military” state—all the liberty-killing “known instruments for bringing the many under the domination of the few,” Madison concluded.

As the partisan press battle blazed with a swollen-veined passion equal to the most rabid fringes of today’s blogosphere, the president never employed the power the Alien Act gave him to deport any noncitizen he deemed a national security threat, even though he believed that the country “swarmed” with “Spies in its own Bosom.” But the government did bring prosecutions under the Sedition Act, which criminalized “false, scandalous, and malicious writing” intended to bring the president or Congress “into contempt or disrepute, or to excite against them . . . the hatred of the good people of the United States.” Madison proposed a mordant July 4 toast: “The freedom of speech; May it strike its enemies dumb.” But joking aside, since the act forbade conspiring “with intent to oppose . . . measures of the government,” Madison and Vice President Jefferson, fearful that Federalist spies were opening their mail, worried about prosecution as they conspired in figuring out what to do. Indeed, an uncharacteristic six-month break in the correspondence between the author of the Declaration of Independence and the Father of the Constitution testifies to their anxiety; their friend and neighbor James Monroe even cautioned them against being seen together on the Piedmont lanes.

Meanwhile, the government indicted no-holds-barred Republican journalist Benjamin Franklin Bache, Founder Ben Franklin’s grandson, for seditious libel, though he died before trial, while Republican hack James Callender got a nine-month sentence and Vermont Republican congressman Matthew Lyons got four months and a $1,000 fine for volunteering, with some truth, that Adams had “an unbounded thirst for ridiculous pomp, foolish adulation, and selfish avarice.” He won reelection from jail.

The Piedmont co-conspirators responded by writing resolutions that two state legislatures passed. Jefferson drafted one for Kentucky, declaring that, because the Constitution was a pact among the states to delegate certain limited and enumerated powers to the federal government, the states might justly complain if the federal government exceeded those powers, as it did in the Alien and Sedition Acts, and might declare its action “void and of no force.” In fact, read Jefferson’s draft of the Kentucky Resolutions, “where powers have been assumed which have not been delegated, a nullification of the act is the rightful remedy.” The Kentucky legislature, however, dropped the word “nullification” from the resolution it finally passed.

Madison too shied away from the extremism of nullification in his Virginia Resolutions, and though Jefferson slipped the phrase “utterly null, void, and of no force or effect” into one draft of them, the words never appeared in the final copy. The resolutions Madison wrote declared that the “unconstitutional” Alien Act “subverts the general principles of free government,” overturning the separation of powers by making the president both judge and jury in deciding whom to deport.

Worse by far, the Sedition Act violates the Virginia ratifying convention’s solemn statement “that, among other essential rights, the liberty of conscience and of the press cannot be cancelled, abridged, restrained or modified by any authority of the United States.” The act usurps a power that the Constitution not only doesn’t confer but indeed positively forbids in the Bill of Rights—and the usurpation “ought to produce universal alarm, because it is levelled against the right of freely examining public characters and public measures, and of free communication among the people thereon, which has ever been justly deemed, the only effectual guardian of every other right.” And let’s remember, Madison wrote in a later report on the Virginia Resolutions, “that to the press alone, chequered as it is with abuses, the world is indebted for all the triumphs which have been gained by reason and humanity, over error and oppression.” Without freedom of the press, the United States might still “possibly be miserable colonies, groaning under a foreign yoke.” As for journalistic abuses: out of the clash of assertions and opinions, however false and biased, would emerge truth, he believed, with a radical faith in freedom of thought and expression, and a belief in the power of information, that uncannily prefigure John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty.

As to what to do, the Virginia Resolutions are less clear, merely advising that the states “are in duty bound, to interpose for arresting the progress of the evil” that threatens their citizens’ “rights and liberties.” When in September 1799, Madison, Monroe, and Jefferson gathered at Monticello to discuss how best to proceed, Madison was aghast to hear Jefferson say that Virginia and Kentucky should declare themselves ready “to sever ourselves from that union we so much value, rather than give up the rights of self government . . . in which we alone see liberty, safety and happiness.” Spluttered Madison, “We should never think of separation except for repeated and enormous violations.” He trusted in the wisdom of the electorate and the diffusion of republican culture through the newspapers to right this wrong, and soon enough Jefferson became president and let the Alien and Sedition Acts lapse.

Imagine Madison’s horror, then, when in the late 1820s South Carolinians opposed to a protective tariff began to speak of their state’s right to nullify it, citing the authority of Madison and Jefferson’s Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions. As Vice President (and, later, Senator) John C. Calhoun fanned the flames into the 1830s, the elderly Madison wrote one earnest letter after another, recalling that the Constitution was not a pact among the state legislatures but among “the people in each of the states, acting in their highest sovereign authority,” so no state legislature had the authority to nullify an act of Congress, which was the supreme law of the land. If states seized such authority, they would “speedily put an end to the Union itself.” And to gain what? “The idea that a Constitution which has been so fruitful of blessings, and a Union admitted to be the only guardian of the peace, liberty and happiness of the people of the States comprizing it should be broken up and scattered to the winds without greater than existing causes is more painful than words can express.”

By 1833, Madison noted, northerners began voicing “unconstitutional designs on the subject of . . . slaves” (as Patrick Henry had predicted they would 45 years earlier), and talk in the South had turned from nullification to secession. “In the event of an actual secession without the Consent of the Co-States, the course to be pursued by these involves questions painful in the discussion of them. God grant,” he concluded, that we are spared “the more painful task of deciding them!” The next year, he wrote a note of “Advice to My Country,” to be read after his death: “The advice nearest to my heart and deepest in my convictions is that the Union of the States be cherished and perpetuated. Let the open enemy to it be regarded as a Pandora with her box opened; and the disguised one, as the Serpent creeping with his deadly wiles into Paradise.” However inadvertently, and much to his sorrow, he was complicit in opening the lid of that box, if only a crack, and letting the demons loose. And when his “Advice” first appeared in print in 1850, inflamed states’-rights partisans dismissed it as a forgery.

James Madison was a remarkable mind. But what of his heart—his passions as well as his reason, as he would say? That too is an extraordinary story, with a sadly unpromising start brightening to an unexpectedly happy ending in one of the legendary political marriages in American history.

Madison was not the stuff of which fairy-tale lovers are made. Not for nothing did his detractors dismiss him as “Little Jemmy.” Five foot six at the highest estimate (though some guess five four), slight and delicate in build, he was, one contemporary said, “no bigger than half a piece of soap.” When he first arrived in Congress at 29, one delegate mistook him as being “just from the College.” By his mid-thirties, suffering periodic attacks of “bilious indisposition” and chronic hypochondria, he was balding and wore his powdered hair in a comb-over that ended in a little point on his forehead. In his customary suits of solemn black, with knee breeches and black silk stockings, he looked, thought Jacques-Pierre Brissot de Warville (later a leading Girondin), like “a stern censor, . . . conscious of his talents and duties.”

As a public speaker, swaying back and forth, and consulting notes in his hat, he had, according to an unsympathetic congressional colleague, “no fire, no enthusiasm, no animation; but he has infinite prudence and industry.” By contrast, the Virginia Journal blossomed into verse to praise his Constitutional Convention oratory:

Maddison, above the rest

Pouring, from his narrow chest

More than Greek or Roman sense

Boundless tides of eloquence.

Many observers noted the contrast between his awkward reserve with crowds and strangers, and his genial fluency with intimates. Perhaps Edward Coles, Madison’s secretary and his wife’s cousin, caught it best: “his form, features, and manner were not commanding, but his conversation exceedingly so and few men possessed so rich a flow of language, or so great a fund of amusing anecdotes, which were made the more interesting for their being well-timed and well-told. His ordinary manner was simple, modest, bland, and unostentatious, retiring from the throng and cautiously refraining from doing or saying anything to make himself conspicuous.” But in private, ever since Princeton, he even liked a dirty joke.

Most delegates to the Continental Congress lived in boardinghouses, and at the one that was Madison’s Philadelphia lodging from 1780 to 1793, the Virginia congressman met his New York colleague and fellow boarder, William Floyd, who brought his family to stay in late 1782. Madison, 31, fell in love with the youngest Floyd daughter—Catherine, then 15—and by April 1783, just when Kitty was about to turn 16, Madison wrote Jefferson that he “had sufficiently ascertained her sentiments” and that “the affair has been pursued” so successfully that the “preliminary arrangements” were “definitive”—a roundabout way of saying that the couple were engaged. They exchanged miniature portraits, and when the congressional session ended, the 32-year-old swain accompanied his betrothed and her family on their trip home and stayed for a brief visit.

But in July, in a letter brattily sealed with a blob of rye dough, Kitty wrote Madison to break it off, doubtless because she preferred the young medical student she married in 1785. It’s a problem for biographers that Madison destroyed and defaced most of his personal letters, and asked his wife to burn the remaining nonpolitical ones after his death, but under all the crossings-out of his mentions of Kitty Floyd in his letter to Jefferson on August 11, 1783, the heartache still bleeds: “one of those incidents to which such affairs are liable . . . profession of indifference . . . more propitious turn of fate.” Jefferson replied with the usual bromides, enlivened by his golden pen: “the world still presents the same and many other resources of happiness, and you possess many within yourself.” He had thought the match a done deal, he wrote, “[b]ut of all machines ours is the most complicated and inexplicable.”

As Madison shepherded the Constitution, the new government, and the Bill of Rights into existence, he himself entered into middle age as a confirmed bachelor. But instead of being just a short, slight, balding, diffident middle-aged bachelor, he was a famous and powerful one—so when he asked his friend Senator Aaron Burr in May 1794 to introduce him to Philadelphia’s most eligible young widow, Dolley Payne Todd, she readily, if nervously, agreed to meet the man she called “the great little Madison.” All the young and youngish men of Philadelphia were “in the Pouts” for the famously buxom 25-year-old and would “station themselves where they could see her pass,” one friend recalled. She was “the first & fairest representative of Virginia, in the female society of Philada,” her old friend Anthony Morris wrote, “and she soon raised the mercury there in the thermometers of the Heart to fever heat.” It wasn’t just her external charms that fascinated everyone; she had an inner radiance, visible to all, which she herself summed up better than anyone. “Everybody loves Mrs. Madison,” Senator Henry Clay once said to her, much later. “That’s because,” she replied without missing a beat, “Mrs. Madison loves everybody.”

For all her sunniness, Dolley was acquainted with grief, which perhaps explains her habitual caginess about her past. Her father was a high-principled failure, who therefore inflicted upon his family some of the cost of those principles. He and Dolley’s mother had moved from Virginia to join a Quaker settlement in North Carolina, where Dolley was born three years later, in May 1768. But the Paynes didn’t make a go of North Carolina farming, and, a year after Dolley’s birth, they sold their farm at a big loss and returned to farm in Virginia, with slaves. When Virginia legalized manumission in 1782, the state’s Quakers faced a stern choice: free their slaves, since the Quakers increasingly found slavery morally intolerable, or leave the sect. John Payne chose emancipation, moved to Philadelphia and became a laundry-starch merchant, failed, got thrown out of the Pine Street Meeting for insolvency, shut himself in his room, and died in 1792.

By then, his temperature-raising Dolley had been married for two years to Quaker lawyer John Todd and had borne her first child, John Payne Todd. In the summer of 1793, she gave birth to her second son, just as a horrific yellow-fever plague was about to lay waste to Philadelphia. It killed perhaps one in every ten or dozen Philadelphians and devastated Dolley’s family. After sending her and the babies to the supposed safety of the countryside, John Todd stayed in town to look after his parents, who refused to leave and soon succumbed. By the time John Todd fled, it was too late. He died on October 14, 1793, as did his infant son, leaving Dolley a 25-year-old widow with a toddler to raise.

Seven months later, within days of Dolley’s 26th birthday in May 1794, Burr introduced her to Madison. In June, one of Dolley’s young relatives wrote her that 43-year-old “Mad——” told her to say that “he thinks so much of you in the day that he has Lost his Tongue, at Night he Dreames of you & Starts in his Sleep a Calling on you to relieve the Flame for he Burns to such an excess that he will be shortly consumed.” Madison himself wrote her in August, “I recd. some days ago your [p]recious favor from Fred[ericksbur]g. I can not express, but hope you will conceive the joy it gave me.” In September, they were married at Harewood in West Virginia, home of Dolley’s younger sister, Lucy, wife of George Steptoe Washington, the general’s ward and nephew (so interconnected were the Virginia oligarchs).

That day, Dolley wrote to her oldest friend, Eliza Collins Lee, wife of Congressman Richard Bland Lee: “I have stolen from the family to commune with you—to tell you in short, that in the cource of this day I give my Hand to the Man who of all other’s I most admire,” and she signed herself “Dolley Payne Todd.” Later, after Madison had slipped on her tiny finger a ring with a circle of modest diamonds lovingly preserved at Montpelier, she penned this addendum: “Evening: Dolley Madison! Alass!” The paper being torn off at this point, who knows what was in her heart on her wedding night? The Society of Friends, however, knew what it thought of her marrying a non-Quaker 11 months after her first husband’s death: it expelled her.

Beginning in January 1793, when the ever more radical French revolutionaries murdered Louis XVI and the next month declared war on Britain, the Republican embrace of France caused a steady erosion of the party’s influence. When news of the Anglo-French war reached America in April, President Washington issued a proclamation of U.S. neutrality, which Madison attacked as an unconstitutional executive overreach, shredding America’s treaty obligations to France and smacking of British “royal prerogatives.” But also reaching America that April was French ambassador Edmond Genêt, whom Republicans at first tumultuously feted. Soon, though, thumbing his nose at the Neutrality Proclamation by fitting out privateers in U.S. ports to attack British shipping, and threatening to appeal for the support of the American people over the head of the outraged President Washington, he began to “surprize and disgust” even Republicans, wrote Madison. Genêt’s “folly,” he told Jefferson, would “do mischief which no wisdom can repair.”

That summer, as yellow fever decimated Philadelphia, the Reign of Terror decimated France, alienating Americans still further, as they saw the guillotine dispatch friends and allies of their own revolution. Even Genêt, knowing that he wasn’t radical enough for the new Jacobin leaders and so would face the National Razor if he returned home, begged asylum and became an upstate New Yorker. As an exasperated Britain—convinced that U.S. authorities had connived in Genêt’s anti-British antics and dismissive of neutral America’s right to supply France—began attacking U.S. shipping and preparing for wider warfare that the United States could not win, President Washington sent Chief Justice John Jay to calm London’s upset. The resulting Jay Treaty, while it smoothed Anglo-American relations, enraged Republicans by substituting a British treaty for the old Revolutionary alliance with France.

When Washington himself publicly blamed the “self-created” Democratic-Republican societies, formed to back the French Revolution, for fomenting the antitax Whiskey Rebellion in western Pennsylvania in the summer of 1794, Madison lost heart. Federalist journalists had already been calling the societies “Madisonian” and terming their “Jaco-Demo-Crat” members “the Mads”—a dig that stuck. “The game,” said Madison, “was to connect the democratic Societies with the odium of insurrection—to connect the Republicans in Congress with those Societies—to put the President ostensibly at the head of another party, in opposition to both.” By the end of the 1796–97 congressional session, a dispirited Madison, no longer leader of what had been called “Mr. Madison’s Party” or the “French Party,” chose to retire from Congress and take Dolley home to Virginia.

His parents needed him there. As his father, James Madison, Sr., had grown old and frail, Madison’s brother Ambrose had taken over the management of Montpelier. But Ambrose died suddenly in 1793, and when Madison returned home, he grasped the reins of the plantation, enlarged his parents’ brick house to make room for his wife, her young son, and her beloved youngest sister Anna, and became, for the first time, a Virginia farmer.

The Revolution of 1800—as Jefferson dubbed the electoral sweep that gave the Republicans the presidency and control of both houses of Congress—took Madison to Washington for 16 years, first as President Jefferson’s secretary of state and closest confidant until 1809 and then as his two-term successor. Those opening years of the nineteenth century transformed American politics, society, and foreign relations in ways that Madison only marginally controlled; most often, he seemed like a swimmer stroking bewilderedly on time’s ever-rolling stream toward a destination he neither chose nor relished. The magisterial command he showed as a lawgiver deserted him as an executive. Partly because of his deeply ingrained deference to Jefferson, partly because ideology and politics rather than experience and history increasingly became his guide, and partly because he had almost never run anything, he proved no leader at a time when the country badly needed one.

In May 1801, he arrived in the new capital he had won in his bargain with Hamilton—delayed for two months after Jefferson’s inauguration because his father had died in February and he had to wind up the old squire’s affairs before leaving Montpelier to take the oath as secretary of state. The city of Washington, despite architect Pierre L’Enfant’s grandiose plan for its streets and squares, seemed still to be emerging from the primeval ooze. Rotting tree stumps, mud cart tracks, and a sad flock of shanties, falling into ruin even as they were built, punctuated the swampy wastes between its 109 habitable brick houses and 263 wooden ones and promised to doom their “wretched tenants to perpetual fevers,” Treasury secretary Albert Gallatin predicted. For the first few weeks, the Madisons moved in with Jefferson at the unfinished President’s House, still as scantily furnished as when Abigail Adams had used what’s now the East Room to hang out her washing.

Even with Goose Creek off the Potomac ambitiously renamed the Tiber, Washington was still frontier, like so much of the country. The population west of the Alleghenies, 150,000 in 1795, exploded to more than 1 million of the nation’s more than 7 million inhabitants by 1810; that year, 70 percent of the country’s white population was 25 or younger. Young settlers were filling even the frontier parts of settled states: “Axes were resounding and the trees literally were falling about us as we passed,” reported a traveler through the upstate New York woods in 1805. And the 1803 Louisiana Purchase, the Jefferson administration’s greatest accomplishment (or stroke of luck), expanded by 900,000 square miles the frontier yet to settle. As part of the Revolution of 1800, Congress made it ever easier for settlers to buy western land in smaller and smaller parcels, at cheap prices and on easy credit.

What kind of culture would this young, mobile society invent for itself? Above all, Madison and Jefferson vowed, it would be republican. So when Vice President John Adams, at the start of George Washington’s administration, wanted Americans to call their president “His Highness, or, if you will, His Most Benign Highness”—not because he wanted a king but because he sought, through titles, “parade,” and “ceremony,” to harness that “passion for distinction” that he believed to be the strongest motive for virtuous behavior—Madison, resisting anything that smacked of aristocratic or monarchist pretension, persuaded Congress to settle instead on “the President of the United States.” As he saw it, “the more simple, the more Republican we are in our manners, the more rational dignity we shall acquire.”

By manners, he meant more than using the correct fork. He meant, as Hobbes had defined them long before, “those qualities of man-kind, that concern their living together in Peace, and Unity”—the customs and ceremonies, allied to virtue, by which men humanize their interactions: we wait our turn, we dine, we thank, we marry, we mourn. For Madison and Jefferson, republican manners would ban all show of deference or superiority. “The principle of society with us, as well as of our political constitution, is the equal rights of all,” Jefferson explained; “and if there be an occasion where this equality ought to prevail preeminently, it is in social circles collected for conviviality.” With proud simplicity, Jefferson set the tone by walking from his boardinghouse to his inauguration. That day, he declared, “buried levees, birthdays, royal parades, and the arrogation of precedence in society by certain self-stiled friends of order, but truly stiled friends of privileged orders.” Away with George Washington’s controlled, majestic bearing and his yellow coach with six white horses. The slouching Jefferson, when he rode at all, rode in a one-horse cart.

Soon enough, these republican manners created an international incident, when Anthony Merry, Britain’s envoy extraordinary and minister plenipotentiary, came to the President’s House in late 1803 to present his credentials, escorted by Madison and “all bespeckled,” the British legation’s secretary wrote, “with the spangles of our gaudiest court dress.” Jefferson, having by now recoiled against that aristocratic finery and supercilious attitude he had sported in his portrait as ambassador to France, received Merry in sloppy dress and bedroom slippers, lounged in his chair in his characteristic slouch, legs crossed and one hip cocked higher than the other, and dangled a slipper off one toe. Merry took this demeanor as an “actually studied” insult.

His next President’s House visit, a few days later, for a dinner in his and his wife’s honor, confirmed this interpretation. Instead of ushering Elizabeth Merry into the dining room and seating her to his right, as custom dictated, Jefferson offered his arm to a startled Dolley Madison, who whispered, “Take Mrs. Merry.” The secretary of state took charge of Mrs. Merry, however, leaving His Britannic Majesty’s envoy to fend for himself. As Merry pulled out a chair to sit beside the Spanish ambassador’s wife, a young congressman elbowed him aside, and Merry stumbled down the table until he found an empty place.

Making things even worse, the French envoy was there, too, a gross breach of the commonsense diplomatic rule of never inviting representatives of two warring countries to the same event, and Merry later heard with disgust that Jefferson had specially asked the Frenchman to come back from out of town for the dinner. A few days later, the Merrys went to dinner at the Madisons’ and got the same treatment, though this time Mrs. Merry stared down Treasury secretary Gallatin’s wife and displaced her from the seat at Madison’s right hand.

Jefferson was an ex-ambassador to the French court, and he and Madison, as Virginia grandees, knew better than this, as indeed Madison later admitted, when he said that he would have escorted Mrs. Merry to his own dinner table but felt obliged to toe the presidential line. “Mr. Jefferson and Mr. Madison were too much of the gentlemen not to feel ashamed of what they were doing,” the British legation secretary reported, “and consequently did it awkwardly, as people must do who affect bad manners for a particular object.” Their object—in addition to asserting “the right of the government here to fix its rules of intercourse and the sentiments and manners of the country,” as Madison said—was to express resentment at Britain, and Merry got the message all too clearly, as did the Spanish ambassador’s wife, who exclaimed, as Jefferson snubbed Mrs. Merry, “This will be the cause of war!”

Knowing they had gone too far, Jefferson and Madison tried to backpedal; they printed up and presented to Merry a pamphlet misspelled “Cannons of Etiquette,” stating that American diplomatic occasions, large or small, would follow the rule of pêle-mêle, meaning that guests would crowd in and take whatever place they could, though ladies would go first. Merry huffed that they should have told him this before and that he’d seek instructions on how to proceed; meanwhile he continued to turn down President’s House dinner invitations. “I shall be highly honored,” Jefferson acidly remarked, “when the King of England is good enough to let Mr. Merry come and eat my soup.”

But he never did. Convinced by this charade of America’s implacable hostility to Britain and partiality for France, Merry consistently advised his government never to make concessions to the United States or to believe American overtures of friendship. So the “Merry Affair” helped sow the seeds of the War of 1812.

Even those who agree that that government is best which governs least might think that the Revolution of 1800 took a good idea way too far. As “real a revolution in the principles of our government as that of 1776 was in its form,” Jefferson boasted, his was arguably a counterrevolution, a rejection of the Madisonian Constitution’s energetic federal government and a return to something closer to the weaker Articles of Confederation regime. “When we consider that this government is charged with the external and mutual relations only of these states; that the states themselves have the principal care of our persons, our property, our reputation, constituting the great field of human concerns,” Jefferson told Congress in 1801, “we may well doubt whether our organization is not too complicated, too expensive; whether offices and officers have not been multiplied unnecessarily.” He set out to fix all that.

But even in its own terms, Jefferson’s revolution didn’t make sense. Yes, he cut and cut. He dumped all internal excise taxes and fired the tax collectors, slashing the Treasury’s headcount by 40 percent. By 1810, even with the $15 million spent for the Louisiana Purchase, he and Madison had cut the federal debt to half the $80 million it totaled when they began. But they cut muscle, not just fat. They reduced foreign embassies to just three, in Britain, France, and Spain. Jefferson halved military spending, letting the army dwindle to 3,000 men and the navy to the handful of frigates George Washington had built to fight the Barbary pirates, which Jefferson proposed to supplement with a swarm of light, undergunned patrol boats for coastal defense. The federal government claimed responsibility for external relations, but it had trashed foreign policy’s essential diplomatic and military instruments.

That might be less reckless in a time of profound peace, but from 1792 until 1815—before Jefferson became president, in other words, and until midway through Madison’s second term in the White House—more or less continuous war between France and England and their allies and vassals convulsed the globe. True, an ocean appeared to protect America from Europe’s troubles; but French shippers—as well as those from Spain, which declared war against Britain in 1796—dared not run the British naval gauntlet by carrying goods between their West Indian islands and Europe, so American seafarers filled the vacuum. U.S. ship tonnage trebled from 1793 to 1807, American shippers—mostly New Englanders—became the world’s largest neutral carriers, and their profits skyrocketed. So the nation had something to protect, even though Jefferson considered the carrying trade mere unproductive “gambling,” unlike honest agriculture.

A legal fiction made this golden age for U.S. seamen possible. American officials invoked the time-honored international-law precept that “free ships make free goods,” meaning that in wartime, neutral ships had the right to carry any non-war-matériel cargo to belligerents. But Britain countered with its Rule of 1756, which barred neutral ships in wartime from territories that had been closed to them in peacetime, as French and Spanish possessions had been closed to the Americans. So U.S. shippers seized the fig leaf of the “broken voyage.” They carried cargo from the French or Spanish West Indies to the United States, unloaded it and paid the duty, reloaded it and got a tax rebate, and carried it on to Europe as American goods.

This ruse worked fine, both for eastward and westward trade, until the spring of 1805. Without warning, Britain started seizing cargoes from American ships whose captains couldn’t prove that their loads really were bound for or coming from the United States. When Nelson’s crushing victory over the French and Spanish navies at Trafalgar in the fall of 1805 gave Britain total mastery of the seas, American shipping faced even higher risk. Before 1805 ended, British confiscations had cost American carriers millions of dollars, their insurance premiums had quadrupled, and President Jefferson and Secretary Madison had a crisis on their hands.

Napoleon made their troubles worse. His million-man conscript army’s triumph at Austerlitz in December 1805 won him control of the European continent, which he used the next year to choke the British economy through decrees barring any captain who wanted to enter a European harbor from trading with England. If a ship had landed anywhere in the British Empire, European port troops would seize it; if its cargo was British-made or Empire-grown, they would confiscate it. In this life-or-death world war, which ultimately cost Britain over £1 billion and 300,000 dead, London understandably retaliated with its own 1807 Orders in Council, which made any ship trading between continental ports subject to British seizure and required any ship trading with a single continental port to stop in England for a license. Napoleon countered by ordering the capture of any ship that complied with the Orders in Council. American captains, caught between the fell incensed points of mighty opposites, had nowhere to turn.

Nor was that all. In its desperate need for sailors, the Royal Navy not only “impressed”—that is, drafted—men by kidnapping them off British streets and merchant ships, but it also stopped American ships and impressed seamen it claimed were British subjects, especially troublesome in that Britain didn’t recognize the right of Britons to become U.S. citizens. In June 1807, a few miles off the Virginia coast, the British warship Leopard ordered the American frigate Chesapeake to allow a boarding party to search for deserters and, being refused, raked the U.S. vessel with broadside after broadside, killing three and wounding 18 Americans. Then a press gang from the Leopard kidnapped four sailors, claiming they were British deserters, though only one was. An outraged Secretary Madison directed U.S. Ambassador James Monroe to demand release of the seamen and a British promise of “an entire abolition of impressments” of Americans. President Jefferson ordered all British ships out of U.S. harbors.

And what retaliation did Madison propose to this multitude of provocations? With no military force to speak of, the only arrow he had in his quiver was a trade embargo, a weapon of the 1770s that he persisted in believing would work in the new century. But, contrary to what he thought, Britain and France were much less dependent on U.S. trade than America was on European, especially British, trade; British foreign secretary George Canning rightly dismissed the embargo that Congress passed in December 1807, barring all U.S. vessels from foreign trade, as “an innocent municipal Regulation, which effects none but the United States themselves.” How right he was: during 1808, U.S. exports fell 80 percent and imports 60 percent.

Soon enough, too, the bitterly unpopular embargo, along with the viciously oppressive Enforcement Act of 1809 that responded to widespread smuggling by arming the government with search and seizure powers as unconstitutional as the Alien and Sedition Acts, came to feel more like a war against Americans than against Europeans. Echoing the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions of 1798, Connecticut’s governor invoked the state’s duty “to interpose” to protect “the right and liberty of the people” against “the general government.” Before Congress voted to repeal the embargo, effective on Madison’s inauguration day in March 1809, New Englanders were even darkly muttering about secession.

When Madison stood in the Capitol, pale and trembling in his embargo-chic suit of black Connecticut-made cloth, to deliver his first inaugural address on March 4, he inadvertently sounded what was to be his administration’s keynote when he mentioned, with conventional modesty, his “inadequacy to [the] high duties” he was assuming. He spoke more truly than he knew, unfortunately: for he proved an inadequate leader, with feckless subordinates who failed to meet the stern challenges his administration faced. And thanks to his and Jefferson’s ideology, he had inadequate tools to deal with those challenges, and he lacked the leadership skills to get Congress to strengthen or even to preserve those he had. Only the genius and daring of some naval captains off his radar screen, and of a general who won a famous victory after the war he was fighting had ended, saved his presidency from failure and fortuitously gilded it with honor.

As the embargo expired, Congress renewed sanctions against Britain and France but opened trade with the rest of the world, so captains simply lied about their destinations and traded promiscuously. Bowing to reality, Congress reopened French and British trade but declared that if either combatant would drop its anti-U.S. rules, America would forbid trade with the other. A slapstick charade ensued, with both England and France promising to lift their bans but shying away once Madison had made policy changes that left him looking clueless. Whether commercial sanctions can ever substitute for force remains debatable; but one Republican congressman rightly complained that his party’s embargo policy “puts out one eye of your enemy, it is true, but it puts out both your own. It exhausts the purse, it exhausts the spirit, and paralyses the sword of the nation.”

The Twelfth Congress that convened in November 1811 was as solidly Republican as its five predecessors, but its many freshmen included a new breed of western Republican, young War Hawks who thought that Madison’s temporizing appeasement sullied “the honor of a nation,” as one congressman said. Choosing tough-minded newcomer Henry Clay as Speaker, the Congress broke with Old Republican orthodoxy, raising taxes and beefing up the army.

“The business is become more than ever puzzling,” a troubled Madison wrote Jefferson on May 25, 1812. “To go to war with Engd and not with France arms the federalists with new matter, and divides the Republicans. . . . To go to war agst both, presents a thousand difficulties.” On June 1, citing impressment, the Chesapeake, and the Orders in Council, Madison asked the Senate to declare war on Britain, which it did on June 18—though unknown to the president, Britain had already lifted the offending Orders. Federalists voted unanimously against what they called “Mr. Madison’s War,” which one Federalist pamphleteer, exaggerating Madison’s real enough Anglophobia, charged was “undertaken for French interests and in conformity with repeated French orders.”

To administer the war and command the troops, Madison assembled a group of incompetents rarely matched in U.S. history. As part of the Revolution of 1800, Jefferson had raised party loyalty above merit in government appointments; Madison, with no control of his own party, used appointments to appease Republican factions or barons, choosing each official with “an eye . . . to his political principles and connections,” he ruefully sighed, “and the quarter of the Union to which he belongs.” Even so, one party faction blocked his promotion of his first-rate Treasury secretary, Albert Gallatin, to secretary of state, so Madison elevated indolent navy secretary Robert Smith instead, to ingratiate Smith’s powerful senator brother. That breathtaking failure to lead—and “to resist encroachments” of the legislative on the executive department and so to maintain the crisp and clear separation of powers that Federalist 51 had urged—meant in effect that the president would have to keep running the State Department himself. An inoffensive southerner replaced Smith as naval chief, and, for balance, a northern ex-congressman whose father-in-law was also a northern congressman took over the War Department. Both secretaries, one senator grumbled, were “incapable of discharging the duties of their office.”

Incompetence aside, John Randolph warned, the cabinet “presents a novel spectacle in the world, divided against itself, and the most deadly animosity raging between its principal members—what can come of it but confusion, mischief, and ruin?” War Hawk John C. Calhoun wrote more charitably but with no less foreboding, “our president tho a man of amiable manners and great talents, has not I fear those commanding talents which are necessary to controul those about him.”

What instruments did Madison have to fight and finance the war? For his top generals, he named men cut from the same cloth as his cabinet, chosen by the same principles from the aging “survivors of the Revolutionary band.” Sneered John Adams, “Chaff, Froth, and Ignorance have been promoted.” And though the War Hawk Congress approved a larger army, it clung to Republican prejudice against an oceangoing navy, believing that once the war ended, “a permanent Naval Establishment” would “become a powerful engine in the hands of an ambitious Executive,” as one overwrought congressman grimly prophesied, and it would require permanently higher taxes that would “bankrupt” the nation and “end in a revolution.” The previous, orthodoxly Republican Congress had refused to renew the charter of Hamilton’s bank when it expired in 1811, so Madison lost his best tool for borrowing money to pay for the war. By March 1813, Treasury secretary Gallatin warned Madison that the country had scarcely a month’s worth of funds. By November 1814, with no one willing to buy its bonds, the United States defaulted on its national debt.

Madison’s military strategy was to launch lightning attacks on Canada and seize rich swaths of territory before an unready Britain could harden its positions there—an enterprise, Jefferson wrote him, sure to be “a mere matter of marching.” A demoralized London would have to back off as it lost a precious chunk of its empire. Though Madison bustled round the “departments of war and the navy, stimulating everything in a manner worthy of a little commander in chief, with his little round hat and huge cockade,” one official reported, the three-pronged Canadian invasion had a less jaunty result.

To the west, stroke-impaired General William Hull, 59, set out to invade Canada from Fort Detroit, but his detachment of Ohio militiamen refused to leave U.S. territory. Hull returned to Fort Detroit and misguidedly sent orders to evacuate Fort Dearborn in Chicago, surrounded by hostile Indians. On August 15, 1812, the fort’s 65 soldiers marched out: the Indians massacred them, beheading one officer and eating his dripping heart. British general Isaac Brock besieged Hull’s own Fort Detroit and plied him with disinformation about the murderous intentions of the redcoats’ supposedly huge detachment of Indian allies. “My God!” the distraught and petrified Hull cried. “What shall I do with these women and children”—including his own family? With no warning to any subordinate, he surrendered the fort without a shot on August 16. “Even the women were indignant at so shameful a degradation of the American character,” one observer recorded, and an equally indignant court-martial sentenced Hull to death for cowardice and dereliction of duty, though Madison spared his life. Brock claimed the Michigan territory for the British crown.

Commanding the middle prong, at Niagara, was “the last of the patroons,” General Stephen Van Renssalaer, who at 49 had not a shred of military experience. His first effort to cross the river into Canada miscarried, as a traitor stole all his oars. Two days later, he managed to send 600 men across, who, under the command of Colonel Winfield Scott, 26, killed the fast-moving General Brock but got pinned down. When Van Renssalaer ordered his New York militia to Scott’s aid, they too refused to leave U.S. soil. Scott had to surrender with his army.

Jefferson’s ex-secretary of war, General Henry Dearborn—fat, 61, and nicknamed “Granny”—commanded the eastern prong, charged with taking Montreal. He wouldn’t move. When the War Department ordered action, he lumbered from Albany to Plattsburgh and sent troops into Canada, where, after skirmishing with the enemy, they then shot at one another in the dark. As usual, the militia wouldn’t follow the regulars onto foreign soil, and Granny retreated with his 7,000 or so men. The whole Canadian fiasco, even a Republican paper judged, added up to nothing but “disaster, defeat, disgrace, and ruin and death.”

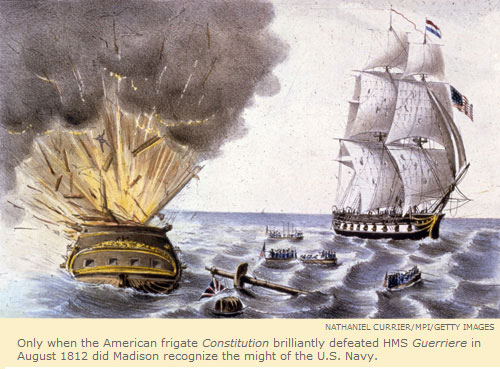

Against that black backdrop, the navy’s brilliant successes shone the more luminously, especially given the cloud of Republican disdain that had hung over that service. In August 1812, the frigate Constitution forced HMS Guerrière to strike her colors after a heart-stopping mid-Atlantic chase and heaven-resounding battle that crippled and dismasted the British vessel and caused one American sailor to cry, “Her sides are made of iron,” when cannonballs bounced off his own ship, instantly nicknamed “Old Ironsides.” An aghast London Times spluttered that “never before in the history of the world did an English frigate strike to an American.” Madison, discarding ideology for the lessons of experience he had formerly valued so highly, sent out his little navy to patrol the high seas in late 1812, where it won renown in victory after victory against a Britannia that had hitherto ruled the waves.

Stephen Decatur, for instance, who at 25 had become the youngest captain in U.S. naval history during Jefferson’s 1804 campaign against the Barbary pirates, when he had daringly sneaked into Tripoli harbor and burned a U.S. frigate grounded there to keep her out of piratical hands, now won further fame when his United States astonishingly brought the defeated frigate HMS Macedonian into Newport harbor as a prize after another mid-ocean duel. More important, since control of the Great Lakes was the strategic key to the Canadian front, was 27-year-old Oliver Hazard Perry’s destruction of the British fleet on Lake Erie in late 1813, in a battle so ferocious he had to switch to a new ship when the British shot his first one out from under him. Another group of American seamen, those who manned the 500 U.S. privateers, proved equally lethal, capturing 1,300 British merchantmen before the war ended.

In a further bow to experience, Madison fired his war and navy secretaries at the start of 1813, and Congress, also educable, voted new ships, more soldiers with better pay, and higher taxes to pay the bills—effective the next year, when it turned out to be too late. But ever-pragmatic Britain learned faster and by the end of 1813 had clamped a blockade on America’s entire east coast, bottling up the U.S. Navy and choking off trade.

When Napoleon’s abdication in April 1814 freed seasoned British troops to turn their full force on America, the outlook darkened ominously. Though a brilliant U.S. naval victory on Lake Champlain stymied the British invasion of New York in September, British troops and ships sailed into Chesapeake Bay and looted, burned, and raped their way toward Washington. Madison ordered his new war secretary, John Armstrong, to strengthen the capital’s defenses, but the pigheaded Armstrong—no improvement on his predecessor, as Madison by then knew from a long train of insubordination and duplicity that a competent leader would have punished with dismissal—disobeyed, convinced that the enemy had targeted Baltimore, even though on August 19 British admiral Sir George Cockburn had sent a message declaring that he’d dine in Washington in two days, take Dolley Madison captive, and display her in triumph in the streets of London.

On August 24, 1814, the British attacked U.S. troops at Bladensburg, Maryland, the overland approach to Washington, 15 miles away. Pluckily, Madison, in his little round hat with its huge cockade, had spent most of six days in the saddle despite his 63 years, stimulating his officers there with all his heart. To no avail: the troops fled in such ignominious disarray that the “battle” became known as the Bladensburg Races. As plucky as her husband, Dolley Madison told her cousin that she did not “tremble” but felt “affronted” when Admiral Cockburn entered the Chesapeake and “sen[t] me notis that he would make his bow at my Drawing room soon.” After all, she said, “I have allways been an advocate for fighting when assailed, tho a Quaker,” and she had her “old Tunesian Sabre within my reach.”

In a famous letter to her sister Lucy, written the night of August 23, added to twice the next day, and clearly edited and copied after the fact, since it is mostly free of Dolley’s endearingly haphazard spelling, Dolley tells of staying in the White House until the last possible moment, “with no fear but for [Madison] and the success of our army,” packing up cabinet papers and valuables, and “ready at a moment’s warning to enter my carriage and leave the city.” The 200 men guarding the White House have melted away; panicked Washingtonians are angry with Madison for bringing war to their doorsteps; her French butler, hired from the Merrys on their departure, remains unconvinced that it would be bad form to booby-trap the White House with gunpowder to blow up the British if they enter.

Dawn of the 24th finds her “turning my spyglass in every direction, . . . hoping to discern the approach of my dear husband.” By 3:00, she can hear the cannon from Bladensburg. A friend who has come to help her escape waits impatiently as she tries to get the huge, full-length portrait of Washington unscrewed from the wall. It’s taking too long. “I have ordered the frame to be broken, and the canvass taken out it is done, and the precious portrait placed in the hands of two gentlemen from New York for safe keeping”—one of the few relics of the original White House on view there today. “And now, dear sister, I must leave this house” or be trapped in Washington. “Where I shall be tomorrow, I cannot tell!!”

A couple of days late but true to his word, Admiral Cockburn marched into the city a few hours after Dolley left her house for the last time. At the Capitol, British troops piled up all the furniture and set it alight, melting the building’s glass and incinerating the Library of Congress. At the White House, finding the table set for a dinner party of 40 Dolley had planned, with the meat still hot, Cockburn and his officers sat down to eat the “elegant and substantial repast,” toasting “Jemmy’s health” in his own good wine, and carrying away Dolley’s cushion, so Cockburn could “warmly recall Mrs. Madison’s seat,” along with one of Madison’s hats and his wife’s portrait, to “keep Dolley safe and exhibit her in London,” the admiral joked. Then 50 men with buckets of burning coals set the building afire from end to end; the “city was light and the heavens redden’d with the blaze,” a witness reported.

The redcoats fired the nearby Treasury at the same moment that the commander of the navy yard ordered his ships and stores torched to keep them out of enemy hands. Dolley could see the blaze from her refuge ten miles away. The next day, when the British accidentally exploded 130 barrels of gunpowder at an American arsenal, the whole city would have burned to the ground but for a providential thunderstorm with freak, hurricane-force winds that turned the sky black as night and extinguished the flames.

In August 1814, peace talks began in Ghent. Britain demanded control of the Great Lakes, an Indian buffer zone shielding Canada, a chunk of Maine, and access to the Mississippi. The no-nonsense American commission, led by Henry Clay and John Quincy Adams, refused. But when British troops moved on from Washington and failed to take Fort McHenry in Baltimore, an American success that Francis Scott Key immortalized in “The Star-Spangled Banner,” and when the Duke of Wellington opined that conquest of America would be difficult—and impossible without control of the Great Lakes—London’s negotiators softened their harsh terms and agreed to a peace that restored the status quo ante bellum. After all, while Americans viewed the War of 1812 as an urgent matter of national honor, reasserting that they were no longer colonial vassals of the British Empire, for Britain it was merely an annoyance, and half the British public didn’t even know their country was at war with the United States.

The commissioners signed the treaty on Christmas Eve 1814. News of the peace had not reached Wellington’s brother-in-law, General Edward Pakenham, however, who had marshaled a 10,000-man army in Jamaica and sailed it to the Louisiana coast to storm New Orleans and pour into the Mississippi valley. Nor had U.S. general Andrew Jackson heard of the treaty. After wresting Alabama from the Creek Indians, he now methodically prepared to wreak equal violence upon the British invaders. With Baratarian pirate chief Jean Lafitte as his unorthodox aide-de-camp, Jackson built defensive earthworks between the Mississippi to the west and an impassable swamp to the east, and prepared his 4,700 soldiers and artillerymen to meet the 5,300 boxed-in British head-on. The unrelenting, close-range cannon, rifle, and musket fire on January 8, 1815, was “the most murderous I ever beheld,” a battle-tested British veteran marveled. The numbers bear him out: 700 Britons killed (including Pakenham), 1,400 wounded, and 500 captured—compared with seven dead and six wounded Americans.

The burning of Washington had at last solidified U.S. public opinion in favor of the war; when the news of Jackson’s victory reached Washington on February 4, the celebratory crowds in the torchlit streets felt the war effort was worth its heavy cost. To crown all, when the peace terms reached Madison on February 13, their mildness amazed him. With their honor vindicated, and the question of impressment made moot by the ending of the European war, Americans believed they had won a famous victory, even though Britain had conceded nothing. They felt all the more victorious when the next month, the U.S. Navy crushed the Barbary pirates for good, freeing all their captives. Madison was the man of the hour, and what one journalist dubbed the “era of good feelings” dawned.