Out in the rolling country just east of Columbus, Ohio, a new—and potentially brighter—American future is emerging. New factories are springing up, and, amid a severe labor shortage, companies are recruiting in the inner city and among communities of new immigrants and high schoolers to keep their plants running. Two new Intel plants, costing $20 billion, will employ 3,000 workers, generate thousands of jobs, and help make the Midwest an integral part of the high-tech economy.

The technology may be new, but what’s drawing these manufacturers to Ohio is something more traditional: its central location, business-friendly atmosphere, and long-standing industrial culture. “We are still at the edge of the farming areas, and people have a strong work ethic,” suggests Jay McCloy, who runs a plant for Mount Vernon, Ohio–based Ariel Corporation, a maker of natural-gas compressors that employs 1,400. “People here think building stuff is better than selling insurance. On a decent salary, you can live a good life in central Ohio.”

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

America’s industrial future may depend on places like Knox County—home to Mount Vernon, where Ariel is now run by its founder’s daughter, Karen Wright—and, just to the south, Licking County. With a population of 176,000, just a 45-minute drive from Columbus, Licking County has seen its unemployment fall below 3 percent, outperforming the rest of the state and more than 50 percent lower than the rate in major cities like New York, Los Angeles, and Boston. If America recovers its manufacturing mojo, this is the region where it will happen.

Not long ago, Ohio was a classic Rust Belt state, with high unemployment, massive outmigration, and a prevailing sense that time had passed it by. Between 1990 and 2010, Ohio lost more than 420,000 factory jobs. Then things started to turn around, as the state gained back nearly 100,000 industrial positions over the next decade, until the pandemic interrupted that growth. Local observers trace this success to the shale boom in the state, pro-business gubernatorial administrations, and aggressive training programs.

This is more than an Ohio phenomenon. Almost all the states with the fastest industrial growth are outside the coasts, led by Texas, Michigan, Florida, Kentucky, Tennessee, Arizona, Ohio, Minnesota, and North Dakota. Unsurprisingly, these are also the states that, according to Supply Chain Digest, offer the best conditions for manufacturers. Of the magazine’s top ten, all are in the South, the Midwest, or the Mountain region. Sadly, this recovery doesn’t yet include old industrial superstars like Chicago or Detroit. The new industrial wave is sweeping through places with diversified economies, paced by universities, good government services, and some tech-related businesses.

In Ohio, new plants are popping up in numbers second only to Texas. To put this in context, Ohio is booking new capital projects on a per capita basis at a rate almost 14 times that of California, according to a recent Hoover Institution study. “We really need practical skills more than anything for our business,” notes Andrew Lower of TDK Manufacturing, which makes components for Tesla as well as for semiconductor and medical-equipment firms. Lower helps run the factory floor for the company’s 420-person plant (up from 30 employees in 1999) in Columbus. “There’s an embedded history of manufacturing skills. This is a place that celebrates people who dress in blues and work in a factory.”

Ohio’s industrial revival comes at a propitious time. In 2019, the percentage of U.S. manufacturing goods that were imported dropped for the first time in nearly a decade, notes a recent Kearny consulting study. Much of the shift came as a result of rising wages in East Asia, which has reduced the labor-cost advantage for the region. The Reshoring Initia¬tive’s Harry Moser estimates that 20 percent to 30 percent of production by American firms now taking place abroad could eventually come back.

The pandemic may have accelerated these changes. In the early months of the crisis, the U.S. couldn’t produce medical equipment, notably masks and some drugs, since most production had shifted to China. Even the production of basic chemical products was difficult, and the Covid-driven shortage of chips crippled production of automobiles and other goods. The endless conga line of ships waiting outside the Los Angeles–Long Beach harbor illustrated the dependence of our country on others, including our most powerful rival. What was once seen as an easy transfer of work abroad has become increasingly problematic.

This process is changing the whole opportunity horizon, beyond just the industrial sector. Across the job spectrum, most Heartland states (outside deep-blue Illinois), as well as those in the South and Intermountain West, boast lower unemployment and better job creation than California and most northeastern states. Of the nation’s 51 major metros, Columbus, Indianapolis, Minneapolis, and Cincinnati are among those with the lowest unemployment rates.

Technology could provide a critical boost to the onshoring process. Many Ohio firms, like TDK and Ariel, use cutting-edge technologies like 3-D printers, robots, and computer-controlled machine tools that allow them to produce better and often cheaper products. John Wilczynski, executive director of America Makes, a manufacturing consortium funded by the U.S. Air Force and based in Youngstown, says that these “additive manufacturing” processes open new possibilities for companies to lower costs and craft parts that, in many cases, were previously available only in China or other countries. Wilczynski believes that “digitally distributed manufacturing” is key to helping U.S. firms compete more effectively. “The increase in efficiency pays for itself,” he says. “You can reduce the number of components and make them lighter. It is part of what we can do to make us more competitive in the long run.”

New technologies, many emerging from what remains the innovation hothouse of California, are creating the basis for industrial revivals in places like Ohio. For example, virtually all the 13 new battery plants in operation or on the drawing board in the United States are located in the Intermountain West (Nevada), the South (Georgia, North Carolina, Kentucky, and Tennessee), the Midwest ( Ohio), or Texas. California may have developed much of the dazzling technology used in electric cars, but it’s places like Tennessee that are now wooing multibillion-dollar electric-vehicle investments from major U.S. and foreign companies.

The expansion of new semiconductor plants—the spine of the modern economy—may be the most critical factor in any American manufacturing resurgence. In the face of China’s ambition to dominate the production of semiconductors and other advanced technologies, Intel plans to invest $20 billion in two Arizona plants in addition to its new Ohio facility. Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company, for its part, has committed to building a $12 billion new plant in Arizona, while South Korea’s Samsung plans to build a $17 billion facility in Texas. The return of semiconductor production in America has its skeptics, including TSMC founder Morris Chang himself, who says that the costs of operating and building plants in the United States remain too high. Yet even he is investing here. The 90-year-old Chang, whose firm rose in response to U.S. lethargy, may yet prove as inaccurate in this judgment as the leaders of Japanese electronics firms who never imagined losing their leading position to U.S.-based rivals like Apple.

Contrast all this non-coastal industrial activity with the situation in the highly regulated mega-states of California and New York, which rank among the worst performers in American manufacturing growth. California, the ultimate late-twentieth-century advanced industrial power, has hemorrhaged 700,000 industrial jobs in the twenty-first century. New York City, which boasted 1 million industrial jobs in 1950, saw those jobs fall from 200,000 in 2000 to roughly 40,000 today. In February, in what is becoming a pattern, a leading developer of hydrogen cars, Hyperion, moved from Southern California to Ohio, where it hopes to start manufacturing, invest $300 million, and create nearly 700 jobs.

Intel’s choice of Ohio for its largest-ever investment, potentially worth $100 billion, must have surprised those who view the Heartland as incapable of competing with coastal tech centers. (Intel recently warned that groundbreaking plans could be delayed because of stalled legislation in Washington on the CHIPS Act, which would provide significant funding for the project.) But they fail to see the key reason Intel chose to build what could become the world’s largest chip plant 30 minutes from Columbus. Intel’s CEO Pat Gelsinger credited Ohio officials, starting with Governor Mike DeWine, for pursuing his company “very aggressively.” Gelsinger suggested, even more importantly, that lower taxes, less regulation, and a strong commitment to industrial education were critical, as were housing prices, which are far lower than in California. The state also offered $2 billion in incentives, particularly in the form of infrastructure and tax abatements.

The roots of what Gelsinger has dubbed the “Silicon Heartland” lay in policies developed well before the Intel announcement. Ohio’s statewide economic-development organization, JobsOhio, is a private nonprofit funded by revenues from Ohio’s liquor business. JobsOhio proved especially valuable when the uncertainty of the pandemic caused other states to worry about how they would pay for economic development. “The JobsOhio team is unparalleled,” Rick Hanley, CFO of Marxent Virtual Reality, told Chief Executive, the magazine whose annual survey ranked Ohio seventh on its list of best states to do business. “The resources and support that they have been able to provide Marxent solidified our commitment to continuing to grow the company in Ohio.” Peter Anagnostos, vice president of marketing, communications, and business development for MCPc, a technology-solutions provider, concurs. “JobsOhio is allowing MCPc to take a big step toward expanding its capabilities in technology life-cycle management . . . We’ll provide opportunities for the chronically underemployed, for students who will be more likely to remain in Ohio as a result of this experience and for people who are looking for steady employment.”

The Buckeye State, notes Rick Platt, president and CEO of the Heath-Newark-Licking County Port Authority, “never skipped a beat on funding development.” More than 60 such authorities in Ohio work to attract industry with capital financing, infrastructure investment, land preparation, and speculative building development. Such efforts often tend to be largely expensive money-wasters, but in Ohio they have proved more successful. For the past quarter-century, Heath-Newark-Licking County Port Authority has transformed the former Newark Air Force Base into a hotbed of more than 20 companies with a total of 1,650 jobs. The companies operate in fields as diverse as aerospace, medical products, automotive and energy-related products, and even the world’s first organic baby food company, located in the industrial city of Heath (population 10,000), one of four plant-based food firms in the area. Licking County’s manufacturing workforce has expanded by 10,000 this decade.

One of the main obstacles to reindustrialization is a massive labor shortage. U.S. population growth between ages 16 and 64 has dropped from 20 percent in the 1980s to less than 5 percent in the past decade. The shortage is afflicting most industrial economies worldwide. China, with a population expected to shrink by half in less than a half-century, is already seeing a decline in its under-60 population. A lack of new workers is slowing Germany’s formidable manufacturing sector.

The conventional wisdom among pundits and politicians is that the big labor shortages are concentrated in fields employing well-educated professionals. President Biden has talked about having factory workers and oil riggers “learn to code.” But companies are crying out most for skilled, dependable workers who can act as drivers, machine-tool operators, and welders. Due largely to an aging workforce, as many as 600,000 new manufacturing jobs this decade will go unfilled. The shortage of welders alone could grow to 400,000 by 2024. By May 2021, amid a mild economic recovery, an estimated 500,000 manufacturing jobs had no takers. Overall, manufacturing jobs pay over 20 percent more than typical service or retail jobs.

Yet many states continue to funnel kids into the four-year college track, which does little to fill these kinds of jobs. Meantime, according to a 2020 survey, only a third of undergraduates view their educations as advancing their career goals, and barely 20 percent think that a bachelor’s degree is worth the cost. According to surveys by consulting firm EMSI, the vast majority of young people put a higher priority on finding a job that pays well over the social uplift associated with four-year college educations. The up-front investment of college is extraordinarily high—tuition has increased 213 percent in the last 30 years—and returns for many students are not guaranteed.

States like Ohio, Kentucky, and Tennessee have begun putting greater emphasis on skills education, encouraging the training of workers for the realities of the marketplace. The Ohio Association for Career and Technical Education boasts a 98 percent graduation rate, and the vast majority of its graduates find jobs or advance to higher education. Local efforts are important, too. C-TEC (Career and Technology Education Centers) of Licking County collaborates with local companies, high schools, and colleges to train skilled workers. Students who often struggled in high school study subjects such as medical technology and welding and learn to operate complex machinery, including 3-D printers and robotic arms. Joyce Malainy, superintendent of C-TEC, has expanded the center’s apprenticeship program by 29 percent over the past five years and 150 students are now in apprenticeships or training.

Skills-education programs like these do more for working-class families, minorities, and immigrants than any array of “diversity” initiatives. Across Ohio, Malainy maintains, C-TEC has partnered with local NAACP offices and has made efforts to reach out to the less privileged. “If you are young and ambitious, you go into manufacturing and get skills,” notes Gary Schaeffer, director of quality at L Brands’ distribution center at the Personal Care and Beauty Campus, a business park in New Albany. To meet his company’s growing demand, Schaeffer seeks to train the area’s surging immigrant population. The foreign-born population in the area has grown by some 40 percent since 2010, driven largely by Nepalis, Somalis, and Mexicans.

In a sense, these efforts represent a twenty-first-century return of attitudes that helped the Midwest become a global industrial center. Terrence Hayes, who runs Ariel’s 125-person operation in Licking County, suggests that the biggest struggles tend to be not at the top—after all, foreign engineers are plentiful—but closer to the factory floor. “There’s been a period of at least twenty years where we have moved away from practical skills,” he notes. “We would have been better off if there were machine shops in schools like when I was a kid.”

In the future, we may see conflicts between reindustrializers and deindustrializers. As Silicon Valley firms like Intel invest billions in Columbus, most tech and Wall Street firms continue to push business to China, though their enthusiasm has been tested by China’s increasingly authoritarian approach to economic and political matters. Still, Beijing has allies, particularly in Silicon Valley and Wall Street. Apple, for instance, props up and profits from the Communist government’s ever-expanding surveillance state and has announced a $275 billion deal, including promises to keep production in China and to aid Beijing’s efforts to advance its technology capabilities—at a time when the country is determined to supplant the West as the world’s tech leader.

Both the Trump and Biden administrations, in contrast to their predecessors, have shown some awareness of the Chinese industrial challenge. Programs like The BuyAmerican.gov Act and the Make PPE in America Act, as well as recent legislation banning the importation of Chinese products made with forced labor in Xinxiang, illustrate the dynamic. This tough-on-China approach clearly has some popular support; most Americans claim to be willing to pay even higher prices for domestically produced goods, according to a recent survey by the left-leaning Center for American Progress.

But other parts of the progressive agenda could undermine reshoring. If policymakers treat anthropogenic global warming as an existential threat rather than as a long-term nuisance to be managed by adaptation, American industry will suffer. The fashionable goal of “de-growth” to reduce U.S. consumption and lower living standards to “save the planet” is clearly at odds with industrial expansion. (It’s doubtful that China, India, or much of the developing world will embrace such an approach.)

We’re already bearing witness to what “de-growth” policies can do. Manufacturers often cite high energy prices in places like California as a reason not to build there. Low natural gas prices, notes the Cleveland Fed, have been critical to the nascent industrial boom in Ohio and elsewhere. If they want to push both industrial growth and environmentally friendly ends, greens should emphasize less cumbersome interventions, such as expanding remote work and restoring our nuclear power industry.

It’s hard to see how an industrial revival can take place without reliable energy like natural gas and nuclear, as opposed to intermittent sources like solar and wind. But just shifting manufacturing away from notoriously high-carbon supply chains in China, which now emits more greenhouse gases than the United States and the European Union combined, would be a win for the environment.

The United States is blessed with a huge arable land mass, enormous energy and mineral resources, and a large and still-growing population, driven largely by immigration. It still holds an edge globally in innovation, and we could see, as energy and technology expert Mark Mills suggests, a new wave of disruptive American manufacturing companies emerge that use technologies to break old patterns of dependency on scattered supply chains.

This need not end up as a political struggle between rival regions. If California and New York don’t want to get their hands dirty making stuff, then Ohio, Tennessee, Texas, Arizona, and other states are more than willing. There is ample room, in land and ambition, to host a full-scale industrial revival, and economic growth in “flyover country” will generate more demand for software, tourism, and legal, financial, and professional services, which tend to cluster on the coasts. All Americans will benefit if the country can produce the basic goods—in medical equipment, transportation, and technology—that allow the country to remain prosperous and secure.

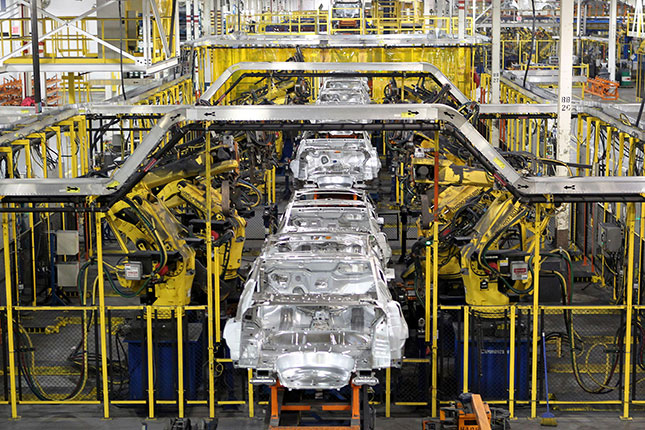

Top Photo: For the past quarter-century, the Heath-Newark-Licking County Port Authority has transformed the former Newark Air Force Base into a hotbed of private business, with 1,650 people working for more than 20 companies. (AP Photo/Jay LaPrete)