Chicago is in the throes of a New York-circa-1970s-style fiscal crisis, with a widening chasm between revenues and spending. Abetted by Illinois’ state government, the Windy City is adopting one of the borrowing tools that helped New York get its finances in order decades ago: a complex municipal bond, structured to protect investors in a possible bankruptcy. But unlike New York, Chicago and Illinois are using this invention to delay necessary budget reform—particularly to unaffordable retirement benefits for public-sector workers—instead of to enable it.

Chicago has spent at least two decades digging itself into a massive financial hole. Back in 2000, the city had racked up $12.3 billion in debt, in current dollars; now, it owes $20.2 billion. Back then, the debt burden per person was roughly $4,400; these days, it’s $7,500. Even scarier is what Chicago owes to current and future pensioners: $31.5 billion, up from a $5 billion estimate in 2000. Last year, Chicago’s pension funds took in $900 million from the city and its employees and earned nearly $541 million in investment income, but the fund paid out more than $2 billion. Chicago actually has less money set aside in its pension funds today than it did a decade and a half ago. As of last December, the funds were less than 25 percent funded—perilously close to becoming another government expense (and a big one) instead of a pension system.

Chicago has zero practical hope of fixing this mess if it keeps to its current path. Since 2000, it has run a budget surplus only once (in 2002), and ended last year $500 million in the red. Though Chicago’s annual pension payments have risen from $500 million to $800 million, the city should be making an additional $1.6 billion payment every year to cover future obligations. Perhaps the reddest flag: Chicago’s school district has been borrowing long-term not to fund infrastructure improvements or maintenance but to pay immediate expenses—a practice that New York City showed in the 1970s doesn’t end well and that no responsible municipality does today.

Illinois and Chicago did try to reform the city’s pension plans, starting in 2014, by reducing benefits and requiring higher worker contributions. But last year, the Illinois Supreme Court struck down the changes, observing that, though “fiscal soundness is important,” the state and city could “not utilize an unconstitutional method”—impairing certain benefits that the state constitution protected—“to achieve that end.”

You would think that bondholders would worry about this unsustainable fiscal reality. Yet last February, they lent Chicago a fresh $1.2 billion, despite warning in bond documents that “the retirement funds have significant unfunded liabilities and low funding ratios” and despite the city holding a junk credit rating from Moody’s for more than two years. Customers were willing to buy the bond, maturing in 2029, at about 6 percent annual interest—considerably above the 3 percent rate that New York could borrow with over the same period, but not sufficient to deter Chicago from borrowing altogether. Increasingly, though, Chicago is worrying that interest rates will rise even higher, making it hard for the city to keep borrowing. The credit cutoff would serve as a powerful signal. Chicago keeps telling retirees and workers, including recent hires, that it can pay pensions that it can’t afford. The city apparently won’t stop doing that—until it is forced to.

Rather than heed the marketplace’s muted alarm, Chicago and Illinois are trying to turn the alarm off. In August, to maintain the city’s ability to borrow cheaply, Illinois passed a law allowing Chicago to issue debt under a far more complex structure than regular “general-obligation” bonds. Some background: a city borrows, in general, to build or to maintain infrastructure. It typically has two ways to give investors confidence that it will repay that debt. One is via a “revenue bond,” backed by specific user revenues. If a city builds, say, a water-treatment plant, residents and businesses would pay a fee for the water that they consume, and investors can count on that money to repay the debt. Second, in cases where infrastructure doesn’t pay for itself—local roads, for instance—the city will borrow under a “general obligation” and pledge its “full faith and credit” to repay the bond. The implication is that the city will raise taxes or slash spending, or both, if all other repayment efforts fail.

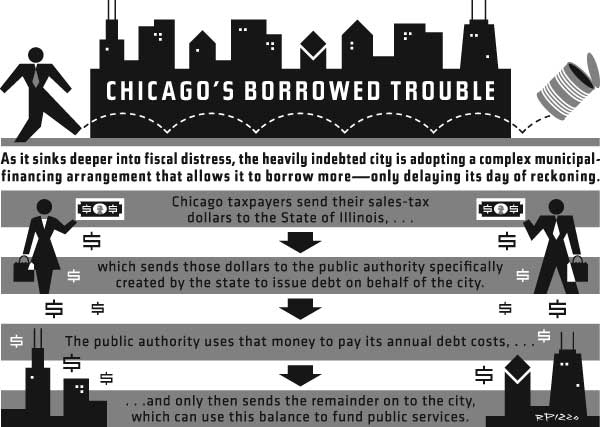

When investors no longer believe in that “full faith and credit,” a city can still borrow money through a third method, pioneered by New York during the 1970s fiscal crisis. Saddled by expanded social-welfare obligations, New York had reached the point where it could no longer repay its short-term debts, yet it needed to borrow more money to fund those obligations, as well as to provide other key services. New York’s financial industry solved this seemingly insoluble problem by inventing a hybrid bond that combined the strongest features of revenue and general-obligation bonds. Albany would set up a new nonprofit entity, known as a “Municipal Assistance Corporation.” MAC, as people soon called it, would borrow the money—and then give it to the city. To repay the debt, MAC would first collect the city’s sales taxes from the state, use those revenues to pay its debt obligations, and only then deliver any leftover money to the city. The sales taxes, in other words, were “securitized”—pledged to protect a certain kind of debt. The new instrument comforted bondholders. They no longer trusted New York City to pay back its borrowing with general tax revenues. But they felt that they could depend on the new state-chartered corporation to collect the money to pay the debt.

The structure, in legal terms, was “bankruptcy remote.” New York could file for insolvency—as was then a real risk—but the sales taxes would continue to repay the special MAC debt, even in such a bankruptcy. Ratings agencies approved the new financial instrument, awarding it healthy “A” ratings even as they suspended the city’s credit ratings in the face of imminent default.

Unfamiliar with the new bonds, investors initially showed minimal interest in buying them. New York State had to win federal guarantees for the city’s debt to help Gotham avoid a sustained default. But instead of being an aberration, New York’s MAC bonds became a template. “The idea of carving out revenue streams that might normally be used for general obligation [bonds] took hold in the New York City financial crisis,” says Joseph Krist, a veteran of that era and a partner at Court Street Group Research, a consulting firm. “We see this same structuring philosophy applied to other situations.”

The structure can have real benefits. First, the ability to borrow through a safer instrument can buy a distressed municipality time to reduce its spending in an orderly fashion. After its 2013 bankruptcy, for instance, Detroit turned to a MAC-style mechanism to issue debt backed by sales- and income-tax revenue. State governments can also use the power that the mechanism affords to oversee local finances, whether through bankruptcy, as in Detroit, or outside of it, as in New York. Yet this form of structured finance has real drawbacks, too—above all, that it can make it possible for municipalities to avoid tackling serious problems for years. In New York State, debt-ridden Nassau County turned to a MAC-type organization, the Nassau Interim Finance Authority, to fund itself when it got into fiscal trouble two decades ago. It’s not clear what has been “interim” about the arrangement—Nassau officials have done zilch since the authority’s creation to get the county finances in order, including failing to cut unpayable future benefits for public-sector workers.

The potential for this kind of irresponsibility is particularly evident in Chicago. Thanks to the new Illinois law, Chicago has followed New York’s 1970s lead, creating a MAC-like organization that is issuing bonds this autumn. Like Gotham, Chicago is securitizing the bonds with its share of state sales-tax revenues. Because the state will pay the interest on the new debt before sending the remaining funds to Chicago, “the city’s hope is to achieve higher credit ratings and reduce debt-service costs,” noted The Bond Buyer, a financial industry publication. “The program is designed to bypass the city’s weak bond ratings by insulating the bonds and assigned revenues from the risk of being dragged into bankruptcy.”

The new bond structure marks the second time in a year that Chicago has issued such tightly structured debt. Last winter, Chicago’s school district—a legally separate municipality, despite relying on the same tax base as the city—issued a half-billion dollars in bonds through a new instrument designed, as Reuters put it, “to separate the debt from the district’s severe financial woes and protect it in a potential bankruptcy filing.” Investors in the new school bonds rely on revenues from a specific capital-improvement tax, again avoiding Chicago’s junk-level credit. Chicago constructed “what they consider this strong bankruptcy-remote structure because of the acute and growing risks perceived by investors related to the general-obligation pledge,” says Bill Bonawitz, director of municipal research at PNC Capital Advisors. Bond raters rewarded the school bonds with a grade of “A,” eight steps above the city schools’ credit rating at the time; as of mid-September, the bonds traded at just above 4 percent annual interest, lower than the school district’s overall cost of borrowing.

Yet this kind of financial mechanism works only if big fiscal reforms accompany it, and, in Chicago’s case, there are reasons to worry. New York State let New York City issue MAC bonds only if it acceded to a state takeover of its finances. Gotham had to pare spending and hike taxes—and then the city struck luck in the early 1980s, when Wall Street took off, bringing in lots of revenues. Chicago, by contrast, will continue to manage its own finances.

Further, the city faces a far more severe long-term financial outlook than New York did. Seventies-era New York experienced a liquidity crisis, which could be solved with higher tax revenues and a reduction in public services. Chicago is looking at a solvency crisis: even with giant tax increases and serious service cuts (both of which could drive away wealthier and middle-class residents), the city is unlikely to be able to make good on its pension commitments. And Illinois, with its own credit rating hovering just above junk and with pension problems in other municipalities, is in a much weaker position to help its marquee city than New York State was decades ago. Indeed, in early September, the state was itself preparing to borrow $6 billion to pay its bills.

It’s not clear that this “bankruptcy-remote” structure really would protect against losses if Chicago defaults on its general-obligation bonds. “The corporate bankruptcy code is very well established,” says Bonawitz, with “a clear line of who gets paid and how.” With the government, he observes, the case law is “very, very limited.” Even with bond prospectuses running to 568 pages, as was true of Chicago’s new school-financing plan, “there’s still a good chance” that issuers and investors “won’t get it right,” Bonawitz adds.

True, New York’s novel bond structure worked; investors were repaid. In fact, the city, despite a AA credit rating and record tax haul, continues to issue MAC-type bonds today, through a public corporation called the “Transitional Finance Authority.” Through the 20-year-old TFA, New York owes $38 billion—almost equivalent to its general-obligation debt. The TFA bonds, backed by the city’s personal income tax and by state payments for school construction, garner a AAA rating—the highest possible—letting New York borrow more cheaply than it can on its general-obligation bonds. But these bonds may work less because of their airtight design than because New York is in such a solid fiscal position, at least for the moment. Elsewhere, municipal borrowers that issued similar bonds and subsequently found themselves in weaker fiscal positions aren’t faring so well—and offer a warning for Chicago.

Take Puerto Rico, even before Hurricane Maria hit. In 2007, the territory’s economy was seemingly doing well, with five straight years of growth, and unemployment falling. Still, it owed 70.2 percent of its GNP, and the government had shut down the previous year in a battle over how to fund a nearly billion-dollar deficit. Officials approved the territory’s first-ever sales tax to finance that gap, but Puerto Rico didn’t trim its bloated budget with the proceeds. Instead, it issued $1.3 billion in new bonds, backed by the sales tax, via a MAC-style outfit, Cofina. The government warned investors that the borrowing was not backed “by the full faith, credit and taxing power of the commonwealth”—but it reassured them, too, that it would collect more than enough from the sales tax to cover payments on the bonds. Investors bought the bonds later that year at below 6 percent interest, similar to Chicago’s cost last February.

Investors comfortable with Cofina made it possible for Puerto Rico eventually to raise $17 billion in new debt, almost as much as it owed in general-obligation bonds. By 2012, the territory owed nearly 100 percent of its GNP—and now its economy was in trouble. Five years later, it would be bankrupt, under a new version of legal default that the federal government authorized for it. Cofina’s structure failed to help Puerto Rico establish financial stability, and it failed to protect investors, too—the territory defaulted not only on its general-obligation bonds but also on Cofina debt. It may be years before Cofina bondholders know whether they will do better or worse than the territory’s general-obligation investors.

Another warning sign for Chicago comes from closer to home. Illinois has done its borrowing through a AAA-rated, tax-backed mechanism called “Build Illinois” for decades. Thanks to the cheap financing, Illinois borrowed more than it otherwise could have. In June, Standard & Poor’s bond-rating agency downgraded Build Illinois’ bonds from AAA, noting that “with the negative pressure on the state’s creditworthiness intensifying, the risk of interference with the flow of revenues pledged to the repayment” of the sales-tax bonds “has increased.” Even without a default, investors in these bonds paid a higher price for a sterling rating, which has been lost. If this tax-backed structure won’t work as advertised on the state level, how can anyone be sure that it will work on the city level?

With no clear precedent to guide them, bond analysts are debating whether structured municipal finance offers much, if any, protection to investors. The pro-protection argument goes as follows. Even if investors in Puerto Rico’s Cofina, say, or in Chicago’s securitized-tax debt suffer losses, they will suffer less than other bondholders. A bankruptcy judge will respect the fact that the elected local government designed the bonds to offer greater protection. “Nothing is absolutely bullet-proof,” acknowledges one top municipal-bankruptcy attorney, but “if you’ve got a lien” in the form of securitized tax revenue, the borrower defaulting on this debt, and thus diverting the collateral behind that lien to other purposes, represents “an unconstitutional violation of the takings clause, the impairments clause.” These structures, he believes, should work “most of the time.”

Contrarians, though, contend that no matter how tangled their borrowing, a state or city has just one tax base and, in a crisis, will have no reason to protect one set of bondholders over another. A bond secured by tax revenues is different, too, from one secured by a more traditional kind of asset, such as a parking garage. As Cate Long, who leads a private research service for Puerto Rico bondholders, notes, a key element of the territory’s insolvency proceedings is whether Cofina funds are “available resources” under the Puerto Rico constitution—“available,” that is, to fund public services and payments to public-sector retirees. If they are available, “then the lien and trust will be broken and Cofina sales-tax revenues will revert to the Puerto Rico general-treasury account,” says Long. The same scenario could arise in Chicago.

In fact, cities and states might have an incentive to favor their general-obligation bondholders. After all, an entity like the one that Chicago is about to create to issue sales-tax-backed debt has no real purpose but to issue such bonds. Like a corporation, it could default, and vanish; Chicago, by contrast, will stick around. The city will want to maintain its ability to issue debt after any bankruptcy, by making good on its general-obligation bonds.

Further, one precedent set in Detroit likely will affect tax-backed bonds. Many investors once thought that municipalities in severe distress would favor bondholders over public-sector workers and retirees. But, as William Sims of the H. J. Sims bond-underwriting firm observes, “the old days of the bonds coming before labor, that has gone.” Concurs Bonawitz, “it’s a lot easier to disrupt bondholder payments than it is to affect employees and pensioners and service recipients. If you’re a bondholder, no matter what the documents say . . . you’re an outsider.”

MAC-style securitized debt for municipalities is a good idea only if it helps them avoid abrupt, radical change—shutting off streetlights at night, for example, to save money. It’s not a good idea when it delays needed change and makes any eventual adjustment—for citizens, taxpayers, and public workers alike—even harsher when it becomes inescapable. In devising legal structures to protect bondholders from a crisis, Chicago may wind up making that crisis worse, when it hits.

Top Photo: Chicago’s school district has used bonds to raise funds for daily operating expenses, not for long-term capital needs. (SCOTT OLSON/GETTY IMAGES)