During a recent visit to Australia, I was treated to Barrie Kosky’s audacious staging of The Magic Flute. I had hoped that it could offer me a break from writing, speaking, and thinking about contemporary China—my principal occupation, these days—but something odd happened. As Mozart’s opera unfolded, the libretto summoned me back to China. This was no surprise, on reflection. The Magic Flute is about the Enlightenment, its promises and underlying violence. For Europeans, the dialectic of Enlightenment—what the Frankfurt School described as a process through which instrumental reason comes to dominate other forms of thought, and the human spirit itself becomes a kind of product—is by now a distant memory. In China, it is a vividly contemporary phenomenon.

The Magic Flute contains considerable violence; at first, both the protagonist Tamino and the audience are led to blame it on depraved passion. Slowly, however, we come to realize that things are more complicated—and that the violence flows directly from the moral commandment to obey reason rather than passion. “Yes, the Temple of Wisdom is in his charge, too.”

The dialectic or, more accurately, the tragedy of Enlightenment first manifests itself when the creations of the spirit take on a life of their own. This kind of externalization has happened in various circumstances historically, as when religion becomes a limit to the very creativity of the human spirit that gave it birth. Cultural objects detach from their creators and acquire their own “needs.” An endless stream of commodities is produced by an industrial and economic system, which has at some point started to follow its own laws, seemingly beyond our control. “The infinitely growing stock of the objectified mind makes demands on the subject, arouses faint aspirations in it, strikes it with feelings of its own insufficiency and helplessness, entwines it into total constellations from which it cannot escape as a whole without mastering its individual elements,” observed sociologist Georg Simmel—dead products and a deadly logic, set apart from the febrile rhythm of life itself and its constant renewal.

Industries and sciences, arts and organizations: all impose their content and their pace of development on individuals, regardless of, or even contrary to, their wishes or needs. The relentless objectification of the human spirit proceeds apace: a photograph copies what before could exist only in the human mind. But how far can the logic of objectification be taken? Only recently have we started to ask whether the human being might be entirely replaced by an artificial construct, a synthetic being taking its place alongside other human creations.

In our time, this discussion normally turns on the possibilities of genetic engineering and human enhancement. We’re troubled by the idea that human beings, while reaching their ultimate perfection as masters of nature, will be turned themselves into manufactured objects. The dialectic of Enlightenment would then reach its foretold conclusion. The transformation of human beings from subjects into objects entails their disappearance as genuine sources of action and autonomous judgment. As the German social theorist Jürgen Habermas describes such an outcome, the participating perspective of an individual existing and developing in time would give way to the perspective of being something made.

But genetic engineering is too narrow a focus in this context. Other areas exist where the displacement of the grown by the made is arguably happening faster, and with more visible consequences. One such area is the city. It’s worth recalling that the Greeks saw the city as a living organism, a source of action and historical change—and superior to the individual in those respects. It is evident that, even under modern individualism, we remain committed to most of that understanding of cities, no matter how unconsciously. Cities, for us, have certain personalities—hard to grasp but each distinct. That explains why we feel duty-bound to preserve cities’ histories, ways of life, and urban characters, even amid rapid economic and population growth. Lenin once called the state the “machine,” and it’s true that as the state grew in size and bureaucratic impersonality, we have often reserved for the city all the human qualities that the state lacks. It is frequently the city, not the state, that becomes the object of our deepest affections and memories, our signal preferences and most treasured adventures.

Can that organic, natural reality of the city be transformed into something artificial? At first glance, it is easy to see how various contemporary developments might point toward a reevaluation of the city as something made or produced. Until recently, industrial culture organized itself around the production of inert commodities. Today, however, we live in the era of the smart gadget—a much better image or metaphor for a city than, say, industrial products like home appliances or automobiles. Or consider social networks such as Facebook. One could think of Facebook as a virtual city. Those who have mastered the technology of connecting people online might be forgiven for thinking that a next step would be to do something like that in the real world. Alphabet, the parent company of Google, has been pursuing its own “urban living laboratory” in Toronto, in a district where it can experiment with new smart systems and advanced planning techniques. Announcing the project in 2017, Eric Schmidt, then Alphabet’s executive chairman, noted that the project’s impetus came from Google’s founders getting excited about “all the things you could do if someone would just give us a city and put us in charge.”

Above all, the Chinese have pushed furthest the notion of the city as product. One of the most important aspects of China’s recent economic development is the profusion of new cities being built from scratch. These aren’t expansions of existing communities but fully master-planned, manufactured centers of economic and social life, often built on newly developed land such as artificial islands or reclaimed desert. On some estimates, China has built more than 600 new cities since the establishment of the People’s Republic in 1949. Some of these manufactured cities have been extraordinary successes. Shenzhen rose from a rice paddy into one of the world’s most dynamic metropolises—its economy is the size of South Korea’s—in just three or four decades. But even Shenzhen pales, compared with the plans for Xiongan in Hebei province, a new city that covers over 770 square miles, more than twice the size of New York City. A 2017 Morgan Stanley report estimated the cost of relocating the area’s current residents as new infrastructure gets built to be $287 billion over the first 15 years.

The temptation to start with a clean slate is easy to understand. China’s largest cities are marred by development problems. To many Chinese officials, the problems are reminders of the country’s failure to master modernization during the century before the Communist Party came to power. The dream of a new country, reconciled with modernity and technology, morphs into a dream landscape of shining new cities. Popular theories of development, moreover, reinforce the view that a country’s economic potential is tightly linked to the quality of its cities. The global competition for power is ultimately not about territory; the economy is what matters. And economic power isn’t about which nation has the biggest companies; after all, firms can relocate or be disrupted. It’s really about “ecosystems”: collections of companies, workers, and consumers; clusters of culture, social life, and economic activity. In other words: cities. The notion of a manufactured or mass-produced city begins to make sense.

Because Chinese society was forced to catch up with the West in a short time, it developed an experience of change very different from—and far more rapid than—what prevails in Europe or the United States. Will China slow down when it feels that it has caught up with Europe and the U.S., or will it keep pushing, developing new technologies with powerful social, political, and human consequences? The next technological revolution will likely be the first led by China, and manufactured cities will be part of that revolution.

China is uniquely situated to revolutionize the way we think about cities. Simon Leys called it the physical absence of the past. As Leys put it, in Europe, despite countless wars and unimaginable destruction, every age has left a considerable number of historical monuments. In China—a handful of famous landmarks aside (and fully reconstructed, in any case)—what strikes the visitor is the absence of physical memory. “Even its most grandiose palace and city complexes stressed grand layout, the employment of space, and not buildings, which were added as a relatively impermanent superstructure,” observed Sinologist Frederick W. Mote. Chinese cities are almost entirely time-free as physical objects, very different from European cities, with their hearts of stone, their sacred bodies inherited from the past.

Not long ago, I walked around Beijing, carrying a map from 1900. A little over a century separates today’s Beijing from the one represented on the map, but the cities are dramatically different, not only in the most obvious ways—the city walls were famously demolished in 1969 to build a subway line—but in the small details. Reading the biographies of Chinese writers or artists, I sometimes try to find the street and house of their birth. Invariably, in Beijing, it no longer exists—and this is true even when the artist or writer has only recently died.

The sad fate of Lao She reveals a striking example of Beijing’s physical mutability. The author of Rickshaw Boy suffered atrociously during the Cultural Revolution. Humiliated and broken, he committed suicide in 1966, drowning himself in Beijing’s Taiping Lake. The lake no longer exists; it was filled with detritus from the destroyed city walls. A tragic fate, to have disappeared in a place that has itself disappeared. What remains is only an echo of the past: a Taiping District, a Taiping train station.

Continuity in China is not ensured by the immobility of inanimate objects but rather by language, literature, and collective memory. China’s older cities are repositories of the past in the special sense that they suggest mental associations—which, in many cases, go back thousands of years. “The past was a past of words, not of stones,” Mote writes. The older cities possess a deeply felt history of human moments: a world of stories, some businesslike, others poetic. When a friend recently suggested that I go sit on the bank of the West Lake and reflect, it never crossed my mind that he meant that I should literally sit by the lake in Hangzhou, with its throngs of tourists; he meant simply that I should stop and think.

As a case study of China’s lack of a physical past, Leys points to the Preface to the Orchid Pavilion, a Jin dynasty work of calligraphy by Wang Xizhi. Some 350 years after the artist’s death, this extraordinary masterpiece came into the hands of Emperor Taizong, who was so fond of it that he ordered copies made. These copies were carved into stone, and rubbings made from the stone. The stones would, in time, be destroyed and the first rubbings lost, but not before other rubbings had been made. It was only after the original work itself was gone, in fact, that the Preface acquired the reputation it enjoys today. Lately, some have even suggested that the original work may never have existed. But consider what this story suggests: that a work of art can be more creative if it isn’t trapped in a singular material object but remains an ideal model, from which new objects can endlessly be obtained.

Chinese modernity may be unhampered by the physical presence of the past, but it still needs to overcome its spiritual presence. The web of stories and words must be overcome; the rule of the past must be replaced with a new rule, oriented toward the future. This might wind up being easier than expected and, when finally attained, more determinate and complete than remaking the physical world.

Mechanical reproduction, as the philosopher Walter Benjamin saw it, introduces an ontological difference in the object being produced. Before reproduction was possible, the object was unique: determined in time and space, with even faithful copies having differences. We still regard a city this way—there can be no other Paris, no second Venice. But if mechanical reproduction were to be applied here, as well, what would it mean? Cities could be copied to the highest standard, as with prints made from a photographic negative.

Comparisons are often made between the contemporary Chinese city and the city of the future depicted in Blade Runner, the dystopian 1982 movie directed by Ridley Scott and loosely based on a Philip K. Dick novel. In fact, the two cities represent nearly opposite concepts. In Blade Runner, the city is a bustling mass of humanity, cluttered with information: advertising, street life and food, graffiti, mixed-language slogans, and bright neon signs. The image of conflicted and struggling humanity is everywhere, even projected—larger than life—onto giant skyscrapers.

The most modern districts of Chinese cities, by contrast, are shiny, slick, and finished—like gadgets made to impress and work as smoothly as possible, but indistinguishable from other products of the same series. Stand in downtown Shenzhen or Qingdao at night, and the scene before you won’t be like Blade Runner, with its evocation of lonely humanity, or like a screen with dazzling advertising spells, but an abstract shape of pixelated colors, the finished and perfect image of computer beauty, the pulsing rhythm of computer power—the city in the age of mechanical reproduction. Sometimes, while driving on Beijing’s third or fourth ring, I have the vivid sense that the city is no longer made of streets and corners and buildings but that it has become an apparatus of cathode-ray tubes, through which people and vehicles are continuously being emitted.

New cities, it’s important to remember, are not a completely new phenomenon. Aristotle credits Hippodamus of Miletus with the invention of urban planning, which he used to great effect in the reconstruction of Piraeus. Alexander the Great founded countless cities in areas from Asia Minor to Bactria to Pakistan, and many had illustrious histories for centuries after. One scholar suggests that the grand total of Alexander’s newly founded cities may have been about 70—an impressive figure for one man and a single lifetime.

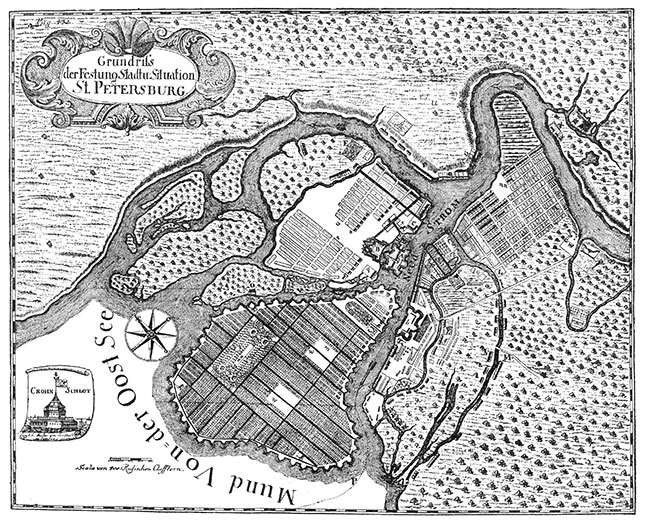

Closer to us in time, Saint Petersburg would appear to approach the ideal of a city built from scratch, in pursuit of a fixed model. Legend has it that, on May 16, 1703, Peter the Great cut two strips of turf, laid them in a cross, and declared: “Let there be a city here.” As he spoke, an eagle flew overhead. It was a beginning, as clear as one might ask. Over the next few decades, thousands of men would lose their lives building a new and brilliant European capital on the Neva swamps—digging by hand and carrying the dirt in the front of their rolled-up shirts, a nearly hopeless endeavor. Saint Petersburg was to serve not only as a window to the West but also as a window to the future, with houses of cut stone rather than wood and majestic palaces and temples devoted to science and discovery. Dostoyevsky called it the “most abstract and premeditated city in the whole world.”

Yet none of these cities can be described as fully made or manufactured. Alexander and Peter regarded themselves as founders; theirs were acts of creation, not production. As Daniel Brook shows in a recent book, the story of Saint Petersburg is complex, with multiple subplots, including the biography of Peter the Great, starting with his youthful indiscretions in Moscow’s German Quarter, and the history of early modern Europe, with Holland’s rise to preeminence, thanks to its privileged access to the seas. The city’s very name betrays these links. And then Saint Petersburg would unsettle and agitate Russian history, setting in motion events that, by the twentieth century—three centuries after its founding—would become global in scope. From the importation of Western ideas to the chaotic urbanism responsible for the growth of an urban lumpen proletariat, Saint Petersburg was fated to become a cradle of political revolution. What Peter the Great managed to achieve was no more than a beginning, after which the city entered the flow of history, not only to make history but also—such is history’s abundance—to be consumed by it.

To borrow a term from Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas, the new cities in China are products of hyper-building. China’s national competition to produce “civilized cities” creates new guidelines by which cities should be measured. They include greening and upgrading of sidewalks but also smart policing through visual recognition, pet management, and the creation of “civilizing barriers” to prevent jaywalking and “civilizing banners” to build spirit. A city cannot hope to receive official recognition—granted by the Central Steering Commission for Building Spiritual Civilization—if it does not subscribe to the accepted models. Once progress is obtained, the guidelines are further developed. Until 2014, China’s National Civilized City Assessment System manual had nine general evaluation categories. The new manual introduced that year featured ten main indexes and 30 points of evaluation.

The city, in this understanding, is no longer a community of life or a subject of economic and social development; it has become a product, evaluated by objective measures and ranked according to what is effectively a price or value matrix. The more that the city approaches this model, the less that it can allow for genuine spontaneity; the stirrings and desires of life can only endanger what it has already achieved. Its inhabitants may begin to long for the time when the city was still something to be done; they had a future then.

Mao famously said: “Beijing, a consumption city left over from the past, must be transformed into a production city.” Once, standing on Tiananmen Square, he pointed south and said that, looking to the horizon, there should be a “forest of chimneys.” Today, he might say that the production city must be transformed into the produced city.

Top Photo: Historic Beijing has all but vanished in the city’s ceaseless reinvention. (IMAGINECHINA LIMITED/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO)