From the mid-twentieth century on, sunny, prosperous Florida epitomized the growing American state. In 1950, Florida had only 3 million residents, ranking 20th in population in the country. By the mid-2000s, it boasted about 19 million residents and had moved up to fourth in state population, behind only California, Texas, and New York. Recent years, though, have seen this upward arc broken. Florida was hard hit when its housing bubble burst in 2007—ahead of the national meltdown that triggered the financial crisis and subsequent recession. When its economy imploded in 2008 and 2009—unemployment eventually rose as high as 11.7 percent—Florida, long a haven of opportunity, became a less attractive place to stay in or to move to. The state’s six-decade run of positive annual net domestic migration (that is, more people arriving in the state than leaving it) came to an end.

Florida’s restrictive land-use policies (better known as “smart growth” or “urban containment”) helped inflate its property bubble to massive size, making its bursting all the more economically painful. Such growth policies limit urban expansion, prohibiting new housing except in small sections of already dense metropolitan areas. As Brookings Institution economist Anthony Downs argues, these policies can destroy the competitive supply of land, driving land prices up (other things being equal) as demand rises sharply in relation to supply. These higher prices get passed along to prospective homeowners in higher home costs—often made even pricier by various other regulations and fees. The rapidly escalating housing prices, in turn, create the potential for extraordinary profits for speculators—or property “flippers”—who, jumping into the real-estate market in considerable numbers, increase the excess of demand over supply, driving prices higher still, until a bubble begins to expand. It’s no surprise that markets with more restrictive land-use policies have much greater housing-price volatility, as research by economists Edward Glaeser and Joseph Gyourko has shown.

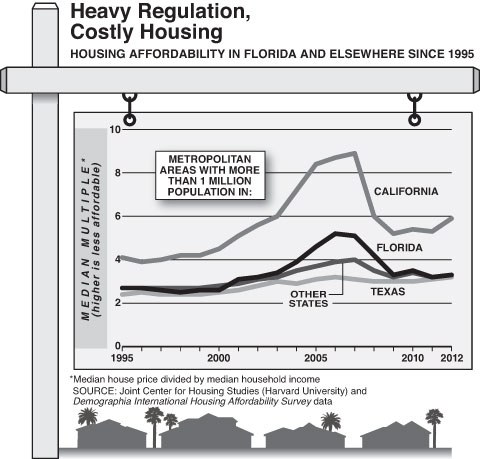

Almost nowhere else in the U.S. did housing prices get more out of whack than in Florida. From 1995 to the bubble’s largest expansion, the median house price relative to median household income (the “median multiple”) in Florida’s four largest metro areas (Miami, Tampa–St. Petersburg, Orlando, and Jacksonville) rose a staggering 93 percent, to 5.2, way above the national postwar norm of 3.0. Only in California—another state with extensive smart-growth policies—did the multiple rise more, at 116 percent, reaching 8.7. In fact, restrictions have become even more severe in California, and the state’s median multiple remains higher than it was before the housing bust. By contrast, in Texas, which has avoided urban containment, the median multiple rose only 32 percent over the same period, to 3.2. Similar, more modest, increases were typical in other lightly regulated areas of the country. When Florida’s housing bubble burst, the damage was great.

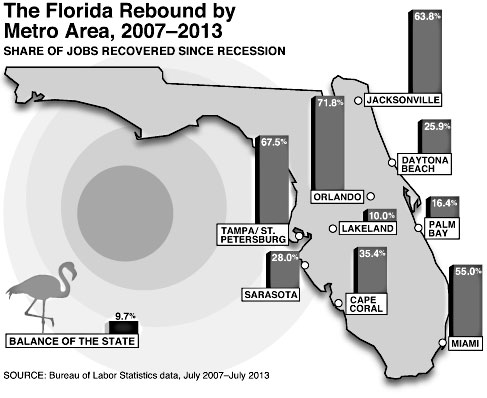

Thankfully, Florida is recovering its vitality. People have started arriving again, with the Sunshine State gaining a net 100,000 residents from other states in 2011 and nearly equaling that total last year. Only Texas has done better over the last two years. An improving economy has helped. Florida’s unemployment rate has fallen to 7.1 percent, and statewide employment is getting closer to prerecession levels. The larger metropolitan areas have done the best: Orlando has recovered 72 percent of its lost job count, Tampa–St. Petersburg 68 percent, Jacksonville 64 percent, and Miami 55 percent. Smaller metropolitan areas—Cape Coral, Daytona Beach, Lakeland, Sarasota, and Palm Bay—have not fared as well, though, and other areas of the state have done even worse. But Florida’s major metropolitan areas—key to economic prosperity, as Glaeser and other economists have argued—have generally prospered over the last decade, the recession notwithstanding, and that’s a good sign for the future.

Business is bullish again, too. This year, Chief Executive rated Florida as the second-best state in which to do business in the country, trailing only Texas, and the fifth-best living environment. The state’s per-capita debt level, at 28th-highest in the country, isn’t stellar but is still 13 percent below the national average—and better than 38th-ranked Texas’s (see “Deep in the Debt of Texas,” Spring 2013).

Cheaper homes have also helped draw residents back. The housing bust lowered Florida’s median multiple by nearly 40 percent between 2007 and 2011, bringing it below the national average of 3.4. More important, the state repealed its smart-growth law, giving local authorities the discretion to allow housing construction sufficient to meet supply, which should keep housing costs in line as the economy continues to improve, preventing the formation of a new bubble. With these hopeful signs, and having weathered the worst of the recession, the Sunshine State may be on its way to a new era of growth and prosperity.