New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg sounds positively exultant these days when he describes Gotham’s economy. “Rising tax revenues are evidence that our economy is strong and growing stronger,” he crowed recently. “Tourism is at record levels.” The businessman mayor also touts Wall Street–fueled wage gains and booming real-estate values—led by double-digit yearly increases in Manhattan co-op prices and the gentrification of neighborhoods like Williamsburg in Brooklyn—as evidence of a turnaround in the city since the terrorist attacks of 9/11.

But hold on a second. The picture is nowhere near as rosy as the mayor paints it. The city’s economy is stuck in neutral, and the budget could be deeply in deficit by next year. After all, though Wall Street’s rebound, boosted by federal tax cuts, has sent tax revenues gushing into the city’s coffers, the Street’s gains have had depressingly little effect on the larger economy.

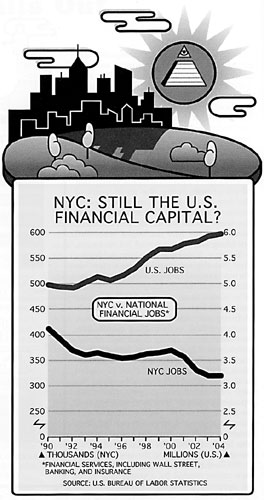

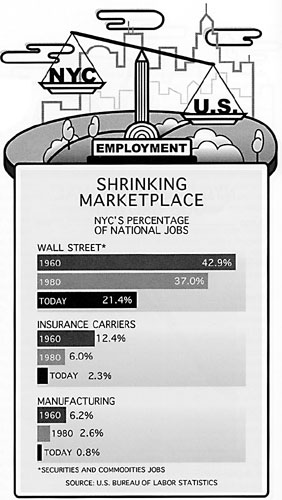

Take the employment picture, above all. Although securities firms added about 3,000 jobs last year (leaving the industry about 32,000 below its former peak), those gains mostly replace continuing losses throughout the rest of the city’s financial-services sectors, as industries like insurance and commercial banking continue to desert the city. Indeed, banking today employs only 39,000 people, down from a peak of 120,000, while the insurance sector, which once employed more than 100,000 people in Gotham, now has only 56,000 jobs. Even growth on Wall Street cannot wholly offset those ongoing declines, which is one reason why financial services continue to shrink in a city that considers itself the financial capital of the world.

Even Wall Street’s future remains an enormous question mark for the city. Just days after Democratic mayoral candidate Fernando Ferrer proposed a $1 billion tax on stock transfers, the New York Stock Exchange announced a merger with Archipelago, a Chicago company specializing in electronic trading. The deal is a sign of the pressure that the NYSE faces from low-cost, high-tech trading systems, and the exchange may soon be forced to abandon its costly trading floor, where about 3,000 people work. More significant, perhaps, is that the NYSE floor is the symbolic headquarters of Wall Street, and if that disappears, it may lead to a broader dispersal of an industry that is already growing faster outside Manhattan. Whereas New York once housed 40 percent of all securities jobs in the country, over the past 30 years the city’s share has shrunk to about 22 percent, and pressure on the NYSE may hasten further declines.

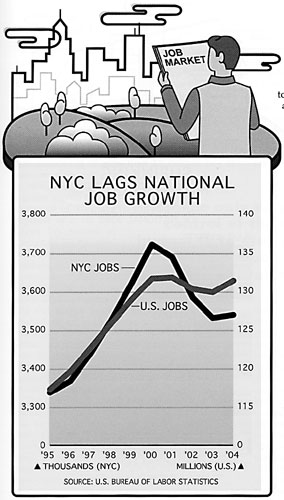

Under Bloomberg, New York is slipping back into an all-too-familiar pattern of lagging behind national job growth, after having outperformed the rest of the nation in the late 1990s under Mayor Rudy Giuliani. Record-breaking profits on Wall Street have not re-ignited growth in business services—the high-paying fields like management consulting, computer technology, and human-resources management that serve corporations. The long exodus of major companies out of New York over the past several decades has gradually pushed these professional-services firms to follow their clients, so that today only 3.2 percent of all business-services jobs nationwide are in New York—down from 11 percent in 1975.

Meanwhile, New York’s outer-borough economies—which contributed nearly half of job growth during the go-go years of the late 1990s—have been mostly going in the wrong direction: through mid-2004, the latest period for which we have data, three of those four boroughs were still shedding jobs in the post-9/11 recession, with only Brooklyn growing modestly. And the city’s manufacturing sector has shrunk beyond recognition, despite predictions that the job losses would eventually slow as a core industrial sector stabilized here. Instead, employment in industry now stands at just 120,000. Sure, manufacturing is dwindling nationwide; but other major cities, including Los Angeles and Chicago, retain hundreds of thousands more industrial jobs than New York, once the nation’s industrial capital with more than 1 million jobs. Even the city’s small-business community, which sparked so much entrepreneurial growth in the 1990s boom, seems demoralized. “This is the worst environment for small business in New York City in 20 years,” the head of a neighborhood retail group recently complained to the city council.

While the mayor touts gains in real-estate prices (fueled by a worldwide surge in property investing) and increases in tax revenues as signs of economic life, the real truth is that New York is no longer a cauldron of economic opportunity. From the start of the last recession just before 9/11 until the end of 2004, the city actually lost a total of 170,000 jobs—a decline of 5 percent. Of course, tens of thousands of those jobs evaporated immediately after 9/11. But the losses nevertheless continued over the next two and a half years, despite Wall Street’s record profits in 2003.

Even in late 2003, when city officials were declaring victory over budget woes thanks to Wall Street’s revival, Gotham was still shedding jobs in construction, advertising, management consulting, manufacturing, and computer services, among other industries. And last year, as the national economy created a healthy 1.5 million new jobs on an annualized basis, the city added a feeble 10,000 new jobs, growth of less than 0.3 percent, or one-fourth the national rate.

Equally troubling, the city slowly seems to be trading its reputation as a financial and mercantile capital for a place as America’s urban theme park and tycoon playground. Although New York is still probably the world’s financial capital, lately the city has mostly been producing employment in low-wage industries that serve tourists and the Bloomberg-style megarich—like restaurants, where the average job pays only about $25,000 a year, and retailing, which pays on average some $30,000 annually.

A big chunk of what has passed for private-sector job growth in New York has also occurred in industries that are nominally private but are actually supported by tax revenues and therefore don’t create wealth but at best merely redistribute it. These industries—health care and social services—have accounted for nearly half the city’s job growth in the past 12 months and now represent 18 percent of all “private”-sector jobs in the city. Moreover, concentrated in areas like nonprofit social-services agencies, home health-care services, and nursing homes, these are mostly low-wage jobs. The typical home health-care job in the city, for instance, pays about $25,000 a year. New York will never earn back its title as one of the country’s leading entrepreneurial centers when tax-supported low-wage jobs account for so much of its economic growth.

Anyone who has watched the long decline of New York’s economy—which today employs nearly 200,000 fewer people than 35 years ago—will understand what’s happening, because it has happened before, repeatedly. The city’s economic slide began in the mid-1960s, when city and state pols began sharply raising taxes to pay for an expanded social agenda—saddling New York with the heaviest tax burden among U.S. cities. Today, Gotham taxes residents and businesses at about 75 percent more than the average of the next ten largest American cities—and that startling percentage is growing. Over the past 35 years, those high taxes have sucked billions out of the private sector, depriving it of needed capital for expansion and ultimately driving away thousands of businesses, including around a hundred Fortune 500 firms, and leaving fewer quality jobs for New Yorkers. A 1997 City Journal study concluded that if New York’s taxes had been in line with those of other old industrial cities, Gotham would have 1 million more jobs than it actually has.

The city’s Giuliani-era economic revival should have provided a blueprint for how to address Gotham’s post-9/11 challenges, for the 1990s was the one period in the last 35 years when the city’s economy outperformed the nation’s, growing by 440,000 jobs and bringing New York back to its 1969 job peak shortly before the terrorists struck. Faced with budget deficits when he took office in 1993, Mayor Giuliani refused to raise taxes but instead shrank the size of government and slowly began cutting taxes. When Wall Street boomed and poured tax dollars into the city’s coffers, Giuliani used the resultant budget surpluses to cut taxes further, reducing the overall tax rate by about 10 percent, still much higher than most major cities. Even so, the cuts sent a message that New York no longer viewed the business community as a gigantic revenue source to be shaken down at every opportunity. Spurred by Giuliani, New York went ten years without a tax increase, although rising profits and property values propelled by economic revival still boosted tax collections and helped fill the city’s coffers.

By contrast, when the city faced new budget deficits after 9/11, Mayor Bloomberg and the city council waved away the Giuliani example and piled on billions in new taxes. To capture even more in revenues, they reassessed real-estate values more aggressively than any suburban politician would even dream of doing. They even jacked up the fines that government levies on businesses—and went about collecting them remorselessly. Some agencies, like the Department of Consumer Affairs, reported a more than 50 percent increase in revenues from violations as they hit businesses with a blizzard of tickets for violations as trivial as incorrect lettering on awnings, while police ticketed commercial vans and trucks for lettering that was too small. “We are being treated as cash cows,” says Sung Soo Kim, the head of the city’s Small Business Congress, a coalition of more than 100 separate groups. He describes the frantic efforts to balance the city budget with dramatically higher fines as a “scorched earth policy” against neighborhood businesses in a city where the hassles of doing business are already enormous.

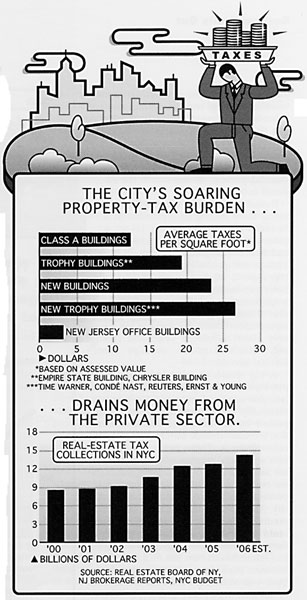

To understand how much more costly Bloomberg’s aggressive tax hikes have made the city, look at the tax-driven price of commercial real estate. With the latest property-tax increases and outlandish new assessments by city tax agents, real-estate taxes now account for on average $12 per square foot of a lease in a Manhattan office building, while in new buildings the tax averages $19 per square foot, and in “trophy” buildings like the Time Warner Center or the Condé Nast tower, real-estate taxes eat up an amazing $26 per square foot, according to the Real Estate Board of New York. By contrast, the average total price of a lease in a New Jersey office building is about $28 per square foot, including only about $3 per square foot in property taxes.

The rising property taxes have put the squeeze on landlords and homeowners and have channeled billions out of the private economy that would otherwise have been used for reinvestment. Total property taxes paid by office-building owners have increased by 50 percent on Bloomberg’s watch, even as their average asking rent has declined by 20 percent. Apartment-building owners are faring even worse. Pressed by tax increases and rising fuel costs, the average apartment-building profit has slumped to 1989 levels, while the number of distressed buildings, whose income doesn’t cover their expenses, has increased to nearly 11 percent of all buildings from about 6 percent five years ago. “A lot of our owners are getting their profits squeezed, especially in the outer boroughs,” says Joseph Strasberg, head of the Rent Stabilization Association, a residential-landlord group. If the worldwide boom in real-estate investing, which has helped provide some owners of distressed buildings a way out of their rental properties by selling them to investors looking for a haven in real estate, should end, New York could easily see a return to the days of rising building abandonments.

Even so, Mayor Bloomberg dismisses criticism of the hikes by observing that New York will always be a premium location—more expensive than most others: “This is still the city where you want to have your company if you want to be successful,” the mayor said after his 2003 tax increase, ignoring the thousands of companies over the years that have fled the city and continued to be successful operating elsewhere.

But even the let-them-eat-cake mayor looks almost prudent compared with the economically devil-may-care city council. Beginning with the 2001 elections, the council—always solidly Democratic—turned radically left as it came under the increasing dominance of former public-sector employees and advocates who gained their political clout running government-funded programs, all of them fervent partisans of bigger government and more regulation. Deep in the midst of the local recession, this aggressively antibusiness and pro-union council passed “living-wage” legislation that forced employers to raise the salaries of 50,000 health-care workers, though economic research consistently shows that such laws destroy low-income jobs. The council has passed legislation limiting the ability of new owners of large buildings to dismiss existing workers. It has lobbied heavily to require owners of buildings in a new waterfront zone in Brooklyn to pay above-market union wages to their staffs, and it has also used zoning laws to stop big retailers like Wal-Mart and BJ’s Wholesale Club from opening stores in the outer boroughs, even though retail employment in those boroughs lags that of the surrounding suburbs where those retailers are allowed to operate.

The economically illiterate council has used its legislative powers to make New York’s biggest problems worse. In a city with a massive and growing housing shortage, in which developers produce new housing at only one-sixth the rate they did 40 years ago, the council passed a lead-paint law that is so tough and filled with potential liabilities for developers that it has helped to stall housing redevelopment around the city—even among nonprofit groups trying to provide housing to the poor. At the same time, the council is using the city’s outdated zoning code to force developers to include subsidized housing in virtually every major new project—increasing the cost for developers in a city that already has the nation’s highest housing-construction costs. The council seems unconcerned not only by the city’s housing problems but by the woes in the construction industry, which has shrunk by 10,000 jobs in the recession.

At the same time, the council has opposed the Bloomberg administration’s laudable efforts to update the city’s nearly four-decade-old buildings code, which forces unnecessary additional costs on builders because it doesn’t recognize advances in building materials or designs, and forces buildings to get exemptions to use the latest techniques. “This is a Christmas-tree code, where every plumbing union, every sheet-metal group, every special interest has hung its ornaments for the last 30 to 40 years,” explains R. Randy Lee, chairman of the Building Industry Association of New York City.

Given the antibusiness policies of the Bloomberg administration and the current city council, it’s hard to imagine how things could get worse. But they can. Campaigning to take Mayor Bloomberg’s job is an array of Democratic hopefuls whose tax-and-spend agenda takes antibusiness, anti-development politics to a whole new level.

Rather than attacking the city’s steep government-imposed costs or proposing to cut business-burdening regulations, they are putting forth tax schemes that would drain still more money from the private sector by targeting some of the city’s most valuable—and vulnerable—industries for new taxes. And they would pump that money into the city’s bloated and dysfunctional educational system or into more hiring and greater benefits for city workers, with no corresponding increase in accountability for how that money is spent. In a city whose government already spends more per capita than any other major U.S. city except Washington, D.C., and where unionized municipal employees enjoy higher wages and significantly greater benefits than their private-sector counterparts, according to a recent Citizens Budget Commission study, the blizzard of tax and spending proposals represents the triumph of the union-led, public-sector coalition that now dominates urban politics and uses its power to wring ever more money out of taxpayers.

Take, for instance, city council president and Democratic mayoral candidate Gifford Miller. He seemingly wants to help drive what’s left of the insurance industry out of New York with one of the most clueless tax proposals in recent memory—a $200 million tax on insurance companies in the city. The Miller-led council made this proposal in its recent budget, even though for decades New York City’s insurance business, once a mainstay of local employment, has been shrinking, as companies flee Gotham’s high costs. Whereas once New York housed one out of every eight insurance-company jobs nationally, today only one in 30 remains here. “They might as well hang an exit sign on the city,” says Bernard Bourdeau, president of the New York Insurance Association.

While Miller would drive away an already-shrinking industry, Fernando Ferrer would target the city’s one economic mainstay to pay for ever more glad-handed education spending. He’s touting a $1 billion stock-transfer tax as an “investment” by Wall Street in the city’s schools to be used to reduce class size—a favorite proposal of the teachers’ union, since it guarantees even more dues-paying members. In defending this risible plan, Ferrer claims that the new levy would fall mainly on day traders and other speculators who had “confused Wall Street with Las Vegas”—an indication of how little he understands how the stock market works. In fact, the tax would fall heavily on big traders like pension funds and mutual-fund operators, who hold and invest the assets of millions of ordinary Americans. Over time, these big traders would find their way around the tax by moving their trading off New York exchanges, thereby further diminishing the city’s place in worldwide financial markets.

The Democratic mayoral candidates also seem intent on driving the high earners who run the city’s mainstay financial industry out of New York. Miller wants to extend the city’s income-tax surcharge on those making over $500,000 a year, so that he can give the estimated $400 million to (you guessed it) the schools, as a sweetener for the teachers’ union. It seems not to matter to either Miller or Ferrer that the city’s school system is already lavishing nearly $20 billion annually—the most of any major school district in America. But improving education is less important than winning the endorsement of the teachers’ union, a startling indication of how far the tax-eaters now control New York City’s agenda.

Queens congressman Anthony Weiner, another mayoral contender, has also leaped on the soak-the-rich bandwagon by proposing to raise rates on those earning over $1 million annually—while cutting rates on those making under $150,000 a year. Though such a plan might seem politically appealing, it is disastrous as a policy, because the combined city and state tax rate for wealthy individuals is already far above that of surrounding areas—or anywhere in the country, for that matter—prompting an outflow of high earners from Gotham. In fact, New York City has the worst rate of domestic outmigration—that is, the rate of those leaving the city versus those moving here from elsewhere in the United States—of any American city, and studies consistently show that the city trades high-income residents who exit for lower-wage foreign immigrants who settle here, a formula that has helped repeatedly create budget crises in the city, since the top 0.8 percent of taxpayers, some 26,000 households out of more than 3.1 million, pay 41 percent of the tax.

Middle-class New Yorkers should also be skeptical of Weiner’s promise of a tax cut, given his record in Congress. He has consistently received a failing grade from the National Taxpayers Union for his votes in favor of more spending and against tax cuts. He even voted against the federal tax package that included the capital-gains and dividend tax cuts that energized Wall Street—an indication of how little he understands how the New York economy works. Just months after 9/11, Weiner told City Journal that he opposed federal tax cuts because “nobody in my district is asking for tax cuts.”

The Democrats’ fourth mayoral candidate, Manhattan borough president C. Virginia Fields, has yet to propose her tax and economic-development policies, but the former social worker has, through her years in the city council and as borough president, supported a long list of social programs that are difficult to pay for without ever-higher taxes.

This bevy of tax and spending proposals has succeeded in driving Bloomberg even further to the left during the mayoral campaign. Pandering to a union audience in May, the businessman mayor endorsed living-wage and prevailing-wage legislation that would raise costs both for government and for private employers. Pressed on how he would handle budget deficits in his second term, the mayor pointed to the tax increases in his first term and intimated that he wouldn’t be averse to further tax hikes on the city’s rich.

These policies of the city’s mayoral candidates, oblivious to the tough road that the city’s economy faces, would pile a heavier load onto an already overburdened private sector. For the past two years New York’s budget has remained balanced only because of extraordinary circumstances—the Washington-driven Wall Street revival in 2003 and a national real-estate refinancing boom last year that helped produce record realty-tax receipts in Gotham, which, unlike most cities, taxes these transactions. But New York cannot count on such circumstances continuing, and the only way to get control of the city’s budget for the long term is to be a revolutionary—to stop piling on new taxes and instead to reduce the cost of city government by cutting both the number of city employees and the size of their absurdly bloated benefits and pensions, and by shrinking costly programs like Medicaid, which current city policies actually encourage to grow. Further, an economic development–minded mayor should eliminate what remains of the commercial occupancy tax, junk the latest property-tax increase on commercial buildings, end the “temporary” surcharge on the personal income tax, and increase the sales-tax exemption on clothing purchases to at least $500, so that the city’s retailers can compete with clothing stores in New Jersey, where there is no tax.

But you won’t hear any of this from the mayor and his Democratic challengers, who seem to have learned exactly nothing from the success of the Giuliani era and to yearn instead, alas, for a return to the New York of Mayor Lindsay or Mayor Dinkins.

Research for this article was supported by the Brunie Fund for New York Journalism.